Frequently asked questions about glaciers. To start with a definition: a glacier is an actively moving mass of snow, firn and glacial ice.

If you have any question not covered in these Frequently Asked Questions, contact me and I will add it to the page!

Glaciers form where the accumulation of snow exceeds melt. When snow accumulates, it gets compressed under its own weight. Freshly fallen snow consists of a lot of air, which decreases when the snow settles. One speaks of firn when the snow has lasted the whole summer. Partial melting makes the snow layer much denser, but firn is still permeable to air. Further compression takes place due to overburden pressure (new snow and firn on top of it). Only when the air trapped inside the firn is no longer interconnected, it is officially turned into ice. This means glacial ice still contains air, but the bubbles are isolated from each other.

In Europe, snow can turn into ice in only twenty years. This is because the more snow falls and the warmer the summers, the sooner snow gets compressed. More snow increases the overburden pressure and higher summer temperatures melt the snow, after which it partly refreezes as ice again. On the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, however, the transformation takes much longer, because of low precipitation and year-round freezing temperatures. In Antarctica it takes up to 1700 years for glacial ice to form.

Gravity pulls the glacier mass downslope under its own weight. Mass accumulates in altitudinal regions because more snow falls than melts and flows downhill, where it compensates the loss of mass due to melt. The movement can occur in three different ways: by internal deformation (ice crystals moving along each other), basal sliding (glacier sliding over its bed) and bed deformation (sliding sediments below the glacier).

Glacier velocity can vary greatly between 1 meter to 1 kilometer per year. They move the fastest where all three processes are active (see above), but in Europe basal sliding accounts for most movement. Commonly, glaciers move in the order of a few dozens to 200 m a year. Because basal sliding depends on the availability of (melt)water, glaciers move faster in the melt season (summer) than in winter. Velocity varies also within glaciers and is highest at narrows, steep steps and halfway their length, where ice transport is highest. Contrary, ice is slowest at both ends of the glacier. Glaciers in very cold regions such as Greenland and Antarctica are frozen to their beds and hardly move at all.

Moraines are landforms composed of glacial till, or in simpler terms: ridges formed by glaciers. Glaciers transport a lot of material like silt, sand and stones and deposit them somewhere. There are many kinds of moraines, but the most common ones are terminal moraines (ridges at the glacier snout) and lateral moraines (ridges at their sides). Because these moraines are deposited at the glaciers margin, the indicate the maximum extent of glaciers. This really helps in reconstructing former glaciations.

Glaciers accumulate snow in their upper regions. Because more snow falls than melts, mass builds up in the form of ice. Due to gravity this ice is transported downslope. The ice reaches lower altitudes where temperatures are higher. The point at the glacier where annual snowfall equals melt is called the equilibrium line. Above this line, the glacier gains weight (mass) and this part is called the accumulation zone. Below this altitude, the glacier loses mass via melting or calving. Therefore, this part of the glacier is called the ablation zone. The glacier mass balance is the sum of mass gain in the accumulation zone and mass loss at the ablation zone. If the mass balance is positive, the glacier grows in weight. If the mass balance is negative, the glacier shrinks.

In a stable climate glaciers are in balance. The accumulation zone (where mass is gained annually) equals the ablation area (where mass is lost annually). In total, the glacier receives exactly as much snow as is lost through melting. But when temperature or precipitation changes, this balance gets disturbed. If it gets warmer or snowfall decreases, the accumulation area decreased. The glacier now has a smaller area to gain mass and a bigger area to lose mass, so the glacier loses weight. Because less ice makes it all the way to its snout, influx of ice is not in balance with melt anymore and the glacier recedes. Conversely, the glacier advances if transport of ice increases because the accumulation area increases at the expense of the ablation area. Eventually, the glacier reaches a new equilibrium.

Worldwide there are over two hundred thousand glaciers. This includes the glaciers of Greenland and Antarctica, though not the ice sheets themselves. These 200.000 glaciers cover approximately seven hundred thousand square kilometers, which is more than the size of France. In the European Alps there are about 4000 glaciers, in Scandinavia 3500 and in Iceland close to 600. But these numbers include a lot of very small glaciers, so it’s better to speak in terms of surfaces: The Alps have 2000 km2 of glaciers, Norway close to 3000 and Iceland over 10.000 km2 (Zemp et al., 2019). To see a map of all glaciers visit https://www.glims.org/maps/glims.

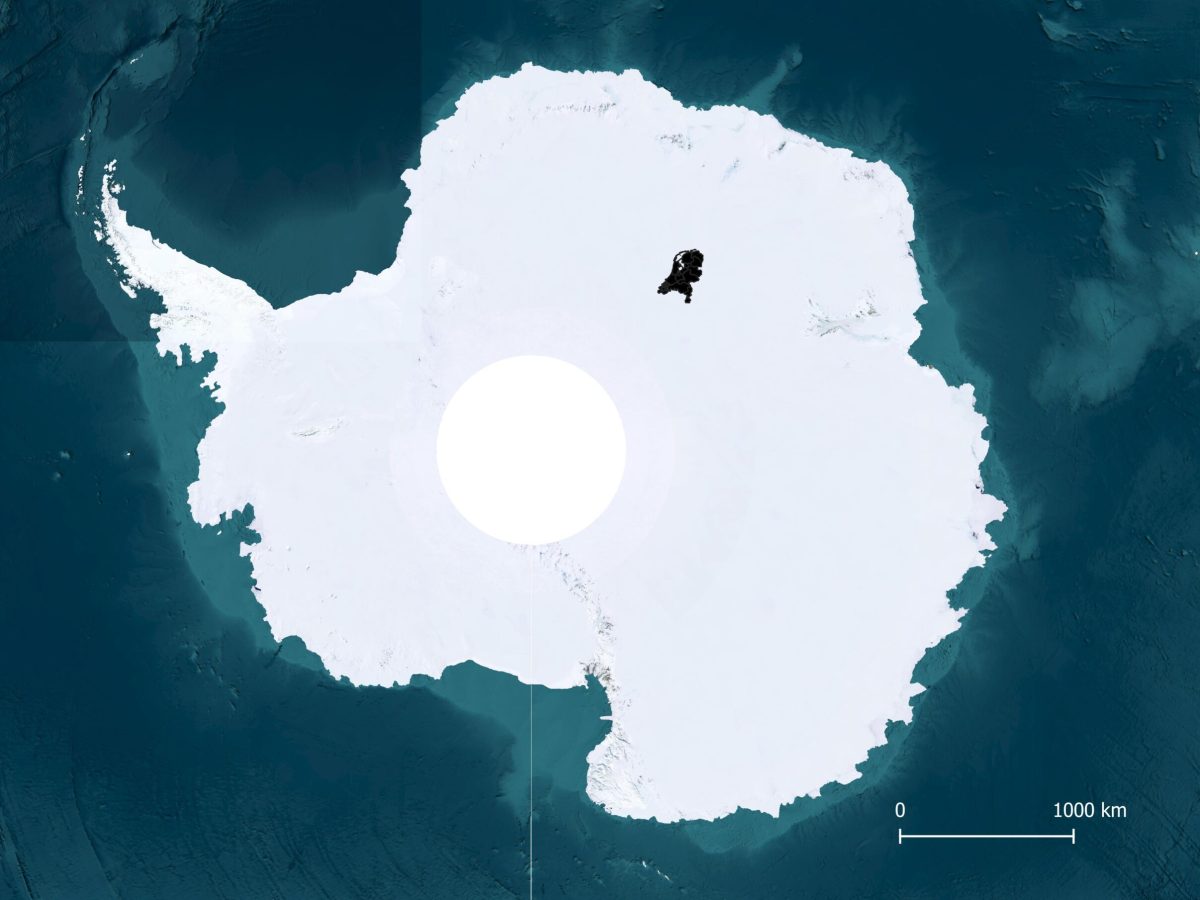

All the glaciers in the world have a total mass of 161 thousand cubic kilometers. If all this would melt it leads to approximately 32 centimeters of sea level rise. The European glaciers in the Alps (100 km3), Scandinavia (300 km3) and Iceland (3500 km3) account for only one centimeter of sea level rise. Much more water is stored in the ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica. Greenland contains 2.850.000 km3 of ice, the equivalent of seven meters of sea level rise. Antarctica has almost ten times more ice and would rise sea levels by almost sixty meters.

Glaciers outside Greenland and Antarctica are losing approximately 200 cubic square kilometers per year. The Greenland ice sheet is losing about 300 cubic square kilometers each year. The Alps and Norway don’t even have that much ice in total, but relatively European glaciers are melting fast. Together, all melting results in two millimeters of sea level rise per year (numbers based on IPCC 2022). The Alps and Norway will lose almost all their glaciers in the course of this century. Iceland is heading in the same direction, but it will take longer to melt its thicker ice.

Search within glacierchange: