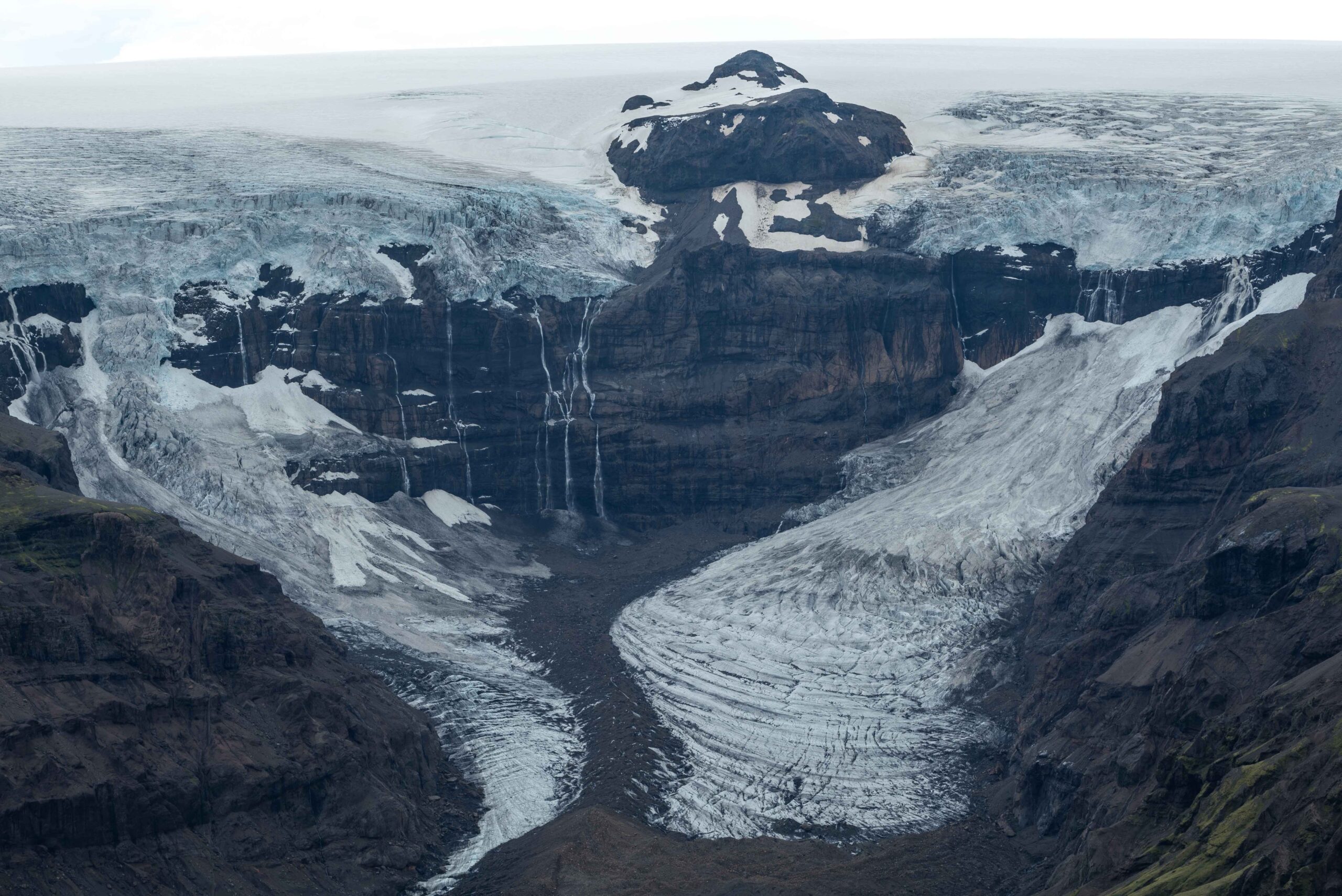

Morsárjökull is a 3 km long outlet glacier north of Skaftafell. Two steep ice cliffs feed the glacier. The sound of falling ice can be heard from afar.

The northwestern branch of Morsárjökull connects to the glacier and is therefore called an icefall, whereas the southeastern one doesn’t and is therefore called an ice avalanche. Where both meet, a medial moraine forms. This is an elongated strip of debris that was at the sides of the glaciers, but become the middle at their confluence.

Not only ice falls down the cliffs, rocks also do. Especially in summertime, resulting in debris-rich ice on the glacier below. This contrasts with ice formed in wintertime, when much less debris falls down. The seasonal difference leaves alternating bands of darker (summer) and lighter (winter) ice in the glacier called ogives. Just as tree rings, one set of bands marks one year of growth. The ogives point towards the valley and this curvature increases downhill, because the middle part of the glacier has a higher flow velocity than the sides.

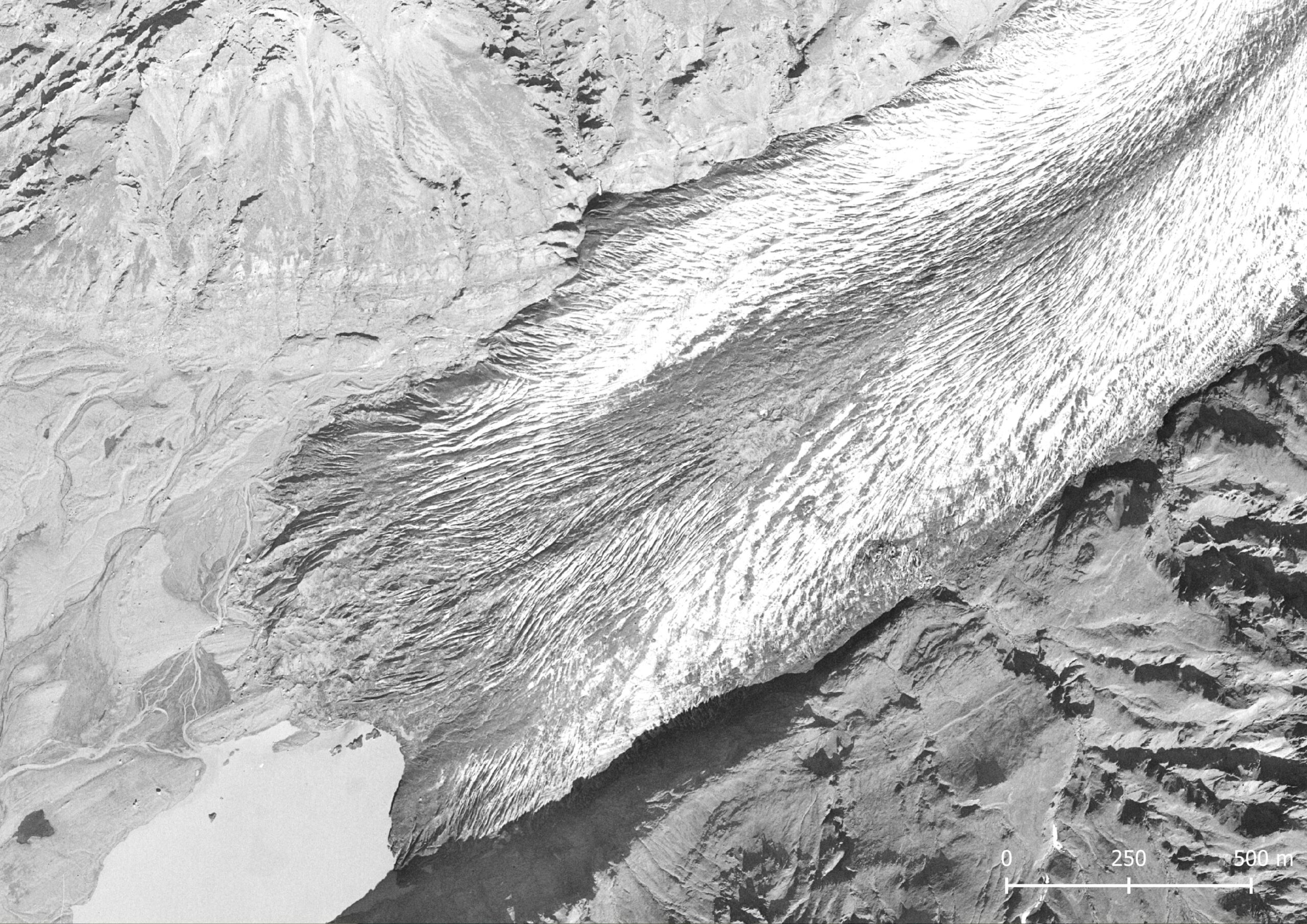

Morsárjökull in 1937 (Ingólfur Ísólfsson, Jöklarannsóknafélag Íslands) and 2023.

Sometimes entire rock faces collapse. The most spectacular event happened in the early spring of 2007, when the largest rock avalanche in forty years fell on top of Morsárjökull. Big parts of the glacier got covered by a layer of debris generally two to six meters thick. It insulates the ice, slowing down melt. Nearby parts of the glacier that are not covered by debris keep melting at a faster rate, so by now the covered parts lay up to fifty meters higher than the surrounding ice (Hermle, 2015).

The debris from the rock avalanche is carried downhill by the movement of the glacier. In the 1950’s, the glacier snout moved at a speed of 100 m per year (King and Ives, 1955). Nowadays the Morsárjökull has slowed down to about 70 m, as a thinning glacier gest slower. Because of this slow but steady forward motion the rock-covered parts of the glacier have recently reached the front of the glacier. As a result, Morsárjökull stopped receding. After all, the ice at the glacier front is now much thicker than it was, thanks to the insulating rocks. It’s a sharp contrast with the glaciers behavior over the years 2000-2018, when it receded thirty meters annually (with outliers of over hundred meters). From 2019 onwards, the glacier advanced slightly.

This period of advancement will be temporarily. The rocks cover 1 km long stretch of the glacier, so the rear end of it will reach the snout position in about fifteen years (given the velocity of 70 m/y). Until then, Morsárjökull is likely to stay more or less at its present position. But behind the debris covered ice the glacier is suddenly tens of meters thinner and recession will swiftly kick in. The melt of the glacier will be augmented by the fact that the snout lies on top of a lake, which will speed up disintegration.

Up to 1940 there was no lake in front of Morsárjökull. Instead, the glacier covered the entire basin and was in 1890 over two kilometers longer than presently. Morsárjökull started receding rapidly from 1930 onwards, like most glaciers in the South of Iceland. This led to the emergence of a lake in the glacial overdeepening, which was later named Morsárlón. The Morsár lake has a depth of sixty meters, is a mile long and can become much larger, because it stretches for at least one more kilometer underneath the glacier.

Morsárjökull in 1997 (Landmælingar Íslands) and 2020 (ESRI satellite).

In between the glacier’s outer moraines of 1890 and the Morsárlón shoreline there are gigantic boulders, uncommon in this part of Iceland. They are predominantly angular and lack the wear features typical of subglacial transport, so they must have been transported on top of the glacier. This so-called supraglacial material must have also broken off the cliff faces and taken downhill by the Morsárjökull (Evans et al., 2017). In this way the glacier works as an enormous conveyor belt, carrying the mountains bit by bit to the sea. But it will break down in the coming decades.

Search within glacierchange: