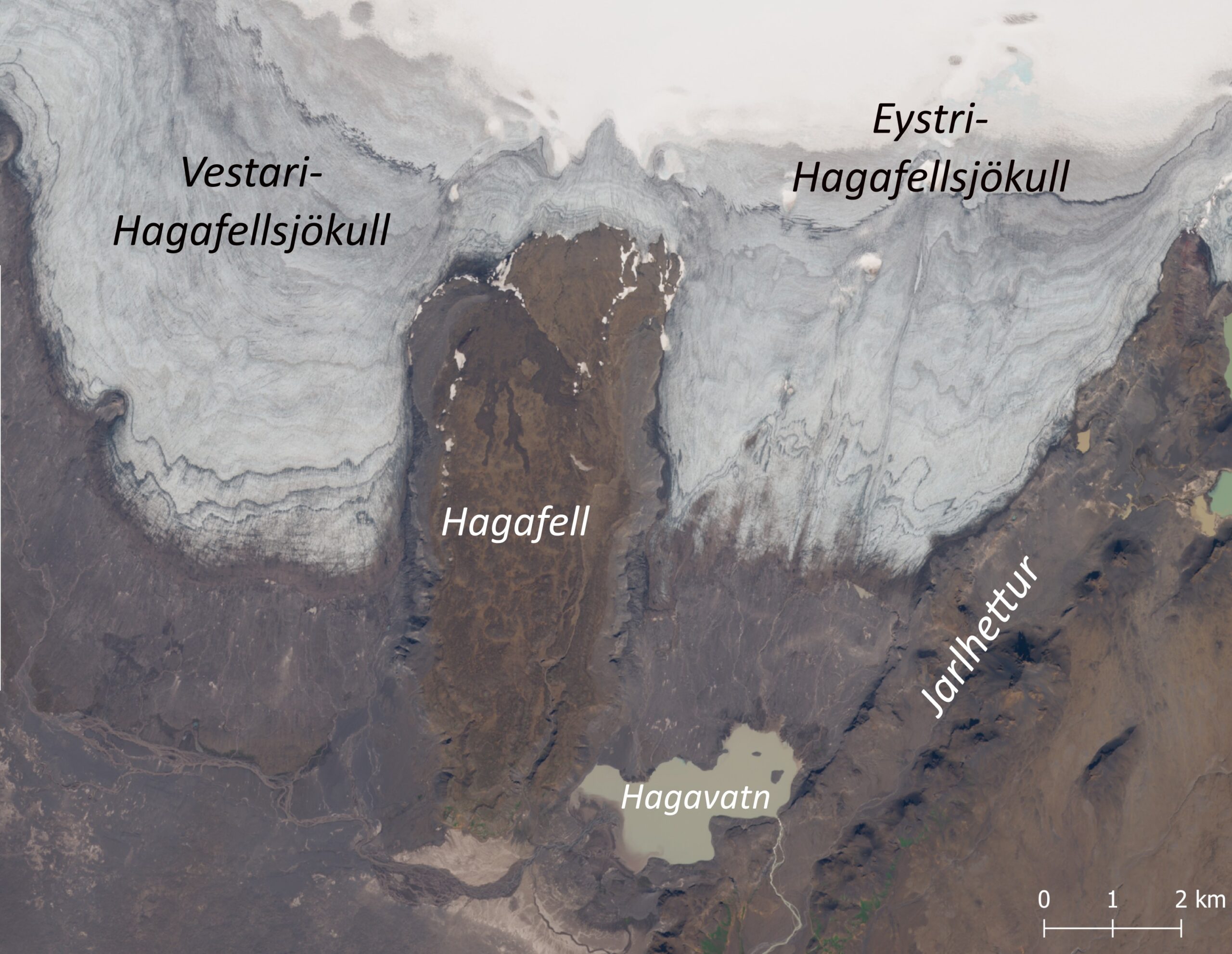

Hagafellsjökull is the southernmost outlet glacier of Langjökull, Iceland’s second largest ice cap. For a long time, the glacier calved into lake Hagavatn.

Hagafellsjökull is split in half by mount Hagafell. Its western (Vestari) and eastern (Eystri) branch both surge, whereby the eastern one terminated in lake Hagavatn until recently. Back in the 19th century, both branches calved into the lake, as Hagafellsjökull was about 5 km longer than presently. The lake and glacier are bounded to the east by a ridge of hills called Jarlhettur. They were formed by subglacial volcanic eruptions along a fissure during the last Ice Age, which ended 11.000 years ago.

When the glacier was much more extensive than now, it dammed Hagavatn’s drainage channel. Subsequently, the water table would rise and eventually burst the dam. Whenever it did, the water harrowed a narrow, deep channel into the soft palagonite. Although a new dam was formed every time, the water level didn’t quite reach the same height as before. Older channels were therefore abandoned as the water table lowered and new ones created. The lake was dammed for the last time in 1939. It’s last outburst channel is now an impressive waterfall, called Nýifoss and Leynifoss (Björnsson, 2017: 294).

Eystri-Hagafellsjökull in 1980 (left) and 2023. Source 1980: Hjálmar R. Bárðarson, National Museum of Iceland HRB1-1980-132-05.

The glacier retreaded from the lake by 1960. In total, Eystri-Hagafellsjökull has receded 5 km since 1890, but with intermediate advances. These events are called surges, in which a glacier suddenly speeds up and can grow by hundreds of metres in a matter of months. The glacier did so in 1974 (by 1200 m) and in 1980 (by 900 m).

The most recent surge occurred in 1998-1999. In the autumn of 1998, the lateral lobes in the east of the glacier surged into the Jarlhettukvísl Valley. When the surge was over in July 1999, the ice had progressed 1160 m. The glacier pushed up a new 2-5 m high moraine that is composed of both brittle and ductile deformed sediments. That means sections of the foreland were frozen when the glacier surged over it, as frozen ground behaves in a brittle fashion under stress. This was only possible because the surge happened in winter (Bennett et al., 2004).

Eystri-Hagafellsjökull finally retreated from the lake around 2010 and is now at 2 km distance from the shore. On the newly exposed surface, there is a large variety of streamlined bed forms. The most prominent ones are flutes: elongated ridges formed on the lee side of boulders, where saturated till (sediments like sands an clay) collects (Hart, 1995).

It is doubtful if the glacier will ever surge again, because the accumulation zone is not thickening. Global warming prevents this driving force of surge events from developing. Instead, Eystri-Hagafellsjökull is more likely to disappear in the coming century and never to advance again.

Orthophoto of Eystri-Hagafellsjökull in 1984 (left) and 2018. Source: Landmælingar Íslands and Loftmyndir ehf.

Search within glacierchange: