Vestre Memurubrean is the largest glacier in Jotunheimen, Norway. In the past it was connected to Austre Memurubrean.

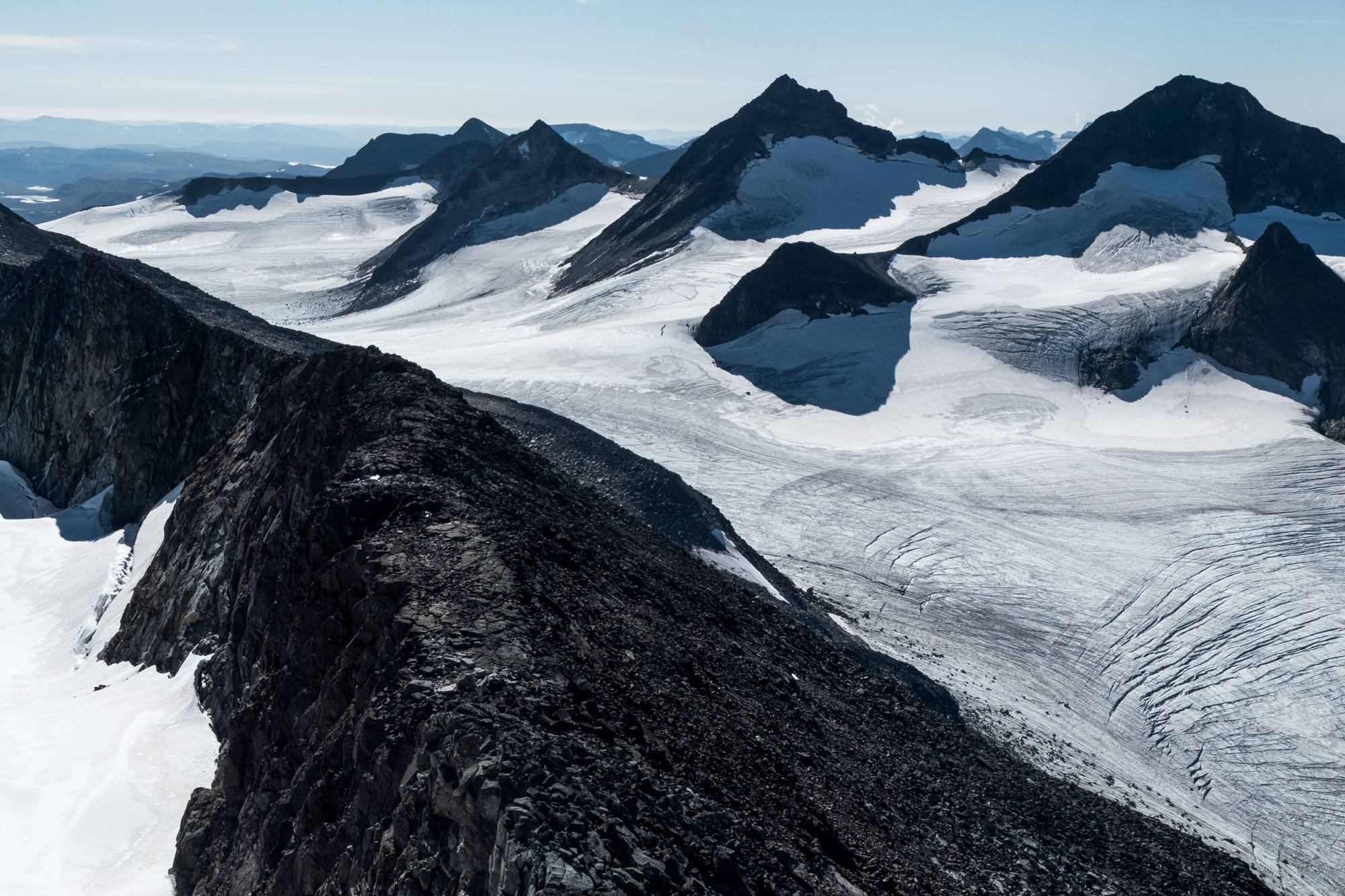

In the heart of Jotunheimen lie two large ice fields: Vestre (Western) and Austre (Eastern) Mumurubrean. They form in cirques around 2000 m and their snouts descend to just below 1700 m. Both glaciers once merged in Memurudalen.

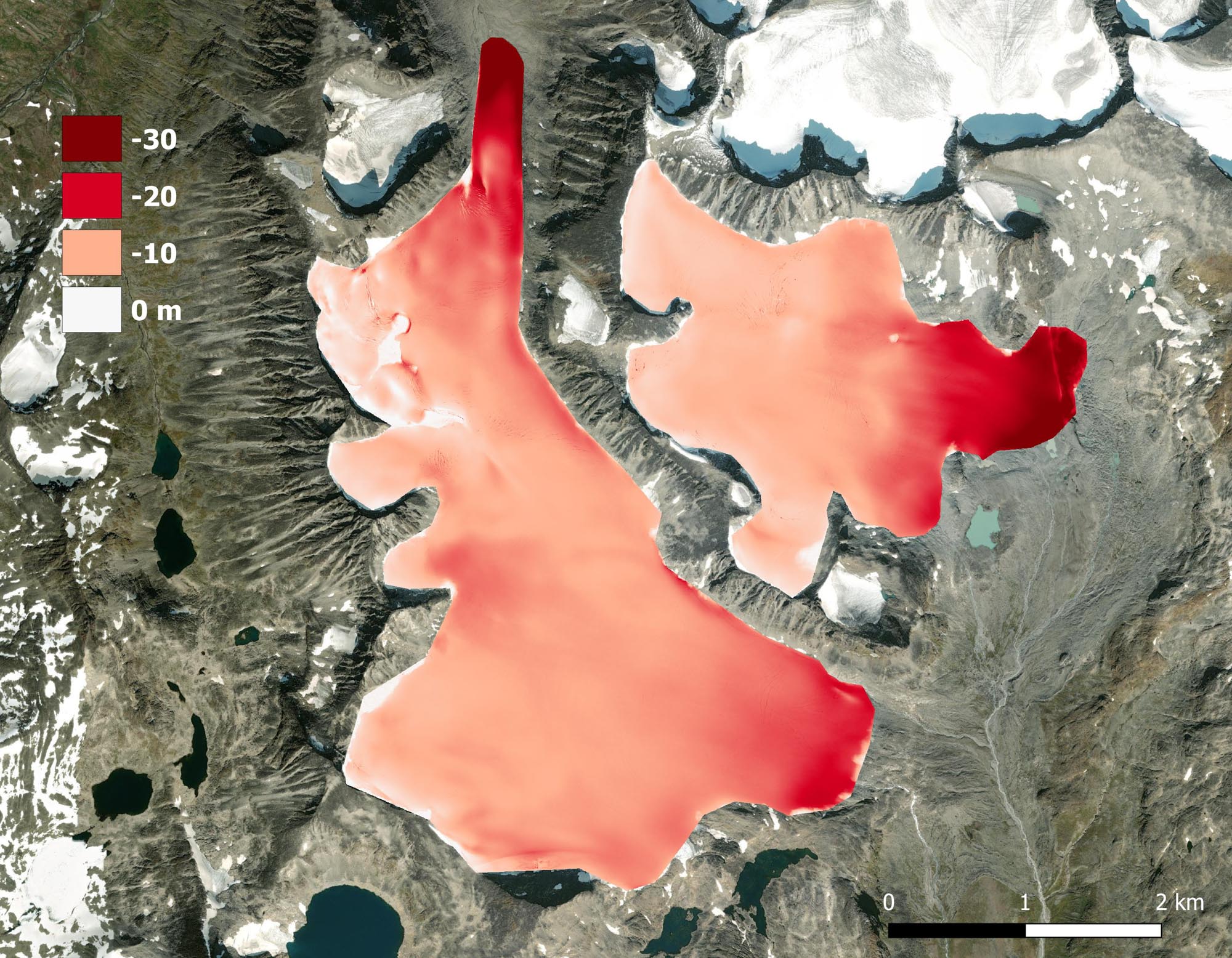

Glaciers in Jotunheimen were at their biggest in the 18th century. In fact, Austre Memurubrean was the largest of them all, measuring 12.4 km2 (Baumann et al., 2009). But it took a hit since then: less than 5 km2 remains as of 2024. Vestre Memurubrean, on the other hand, ‘only’ lost 1.5-2 km2 and is still an impressive icefield of 8 km2. The difference in surface change between Vestre and Austre Memurubeen is a result of the larger area below 1600 m at the latter one (and possibly due to an incorrect distribution of the deglaciated area over the two glaciers).

Vestre and Austre Memurubrean in 1916 and 2024. Source 1916: National Library of Norway photo NF_W_18143_A.

At their furthest point, the glaciers pushed up a terminal (end) moraine. This small ridge of boulders a few meters high shows how far the glaciers advanced in the 18th century. Beneath it, the plants stopped growing immediately after their burial. Such a fossil soil holds clues to past climate change.

Vestre Memurubrean in ca. 1900-1930 (left) and 2024. Source 1900: National Library of Norway.

Scientists have investigated the fossil soil below the outermost terminal moraine of Vestre Memurubrean. In deeper (older) layers pollen of dwarf-shrubs were more common, while closer to the surface pollen reflect a vegetation dominated by grass and heath. This vegetation shift indicates that the climate cooled and snow cover became more persistent (Caseldine & Pardoe, 1994).

Another important aspect of the buried soil is its age. Carbon dating shows that the soil was built up continuously over a period of at least 5000 years and only stopped forming since the glacier covered it during the Little Ice Age around the 17th century. That means that (Vestre) Memurubrean has not been larger in the five preceding millennia (Matthews & Caseldine, 1987).

Vestre Memurubrean shares an ice divide with Hellstugubrean, a rarity in Jotunheimen. Most glaciers in Jotunheimen start off as cirque glaciers surrounded by steep mountain faces. That’s also true for Vestre (and Austre) Memurubrean, except for a 700 m wide pass in the north. Here, the upper part of the glacier joins with Hellstugubreen at 1900 m.

Prior to global warming, snow would survive through summer from an altitude of about 1700-1800 m. But as temperatures rise, so does the summer snow line (which is also called Equilibrium Line Altitude, ELA). Nowadays the ELA is often exceeds the highest parts of the glacier. Consequently, no snow turns into ice anymore. Such glaciers are bound to disappear.

Despite the worrying conditions Vestre Memurbreen won’t disappear within a few decades. In the center, the ice namely is 200-250 m thick (NVE Breatlas). Between 2009 and 2022 the snout lost 20-30 m of its thickness, while the upper parts lowered by about one meter annually. In the same pace it will take two centuries for all the ice to melt. But as the surface lowers, melt will increase and speed up the process. Eventually, a new route from Spiterstulen to Memuru might emerge from underneath the glacier. But will it still be worth the hike by then?

Search within glacierchange: