Nigardsbreen is the most famous and best studied glacier in Norway.

Nigardsbreen in 1872-1875 and 2024. Source 1872: Knud knudsen, Bergen University Library ubb-kk-1318-1040.

Nigardsbreen drains the central part of Jostedalsbreen ice cap to the east and accounts for a tenth of the total area of the ice cap. The S-shaped glacier is some 9 km long and descends to 400 m a.s.l. A hundred years ago the glacier was almost 3 km longer.

No glacier in Norway is better studied than Nigardsbreen. Many scientists have tried to reconstruct how the glacier has changed over time. Luckily, the glacier was already documented in the 1740’s. Back then, local farmers complained about the rapidly advancing glacier. Agricultural land was engulfed by ice, so they appealed to the king in 1742 for tax reductions. Officials were sent for inspections. The next year, barrels of cereal grains and some cash was distributed among the deprived villagers (Gjerde et al., 2023).

A glacier’s advance doesn’t happen overnight. Instead, it is preceded by climatic deterioration. Winters brought much more snow and summers were cooler (Svarva et al., 2018). Farmers in Jostedalen experienced these worsening conditions first hand in the 17th century. Crops were damaged by frost and longer winters shortened the growing season. People were poor, hungry and unable to pay any taxes (Gjerde et al., 2023).

Mjølver village was the most severely affected. In the early 1600’s this village close to Nigardsbreen was one of the best farming areas in Jostedalen. Its best fields were situated in Mjølverdalen, a valley in the path of the approaching glacier. From about 1620 the deteriorating climate impoverished the farmers. Their production capacity for butter, a taxable value at the time, showed a sharp drop (Gjerde et al., 2023).

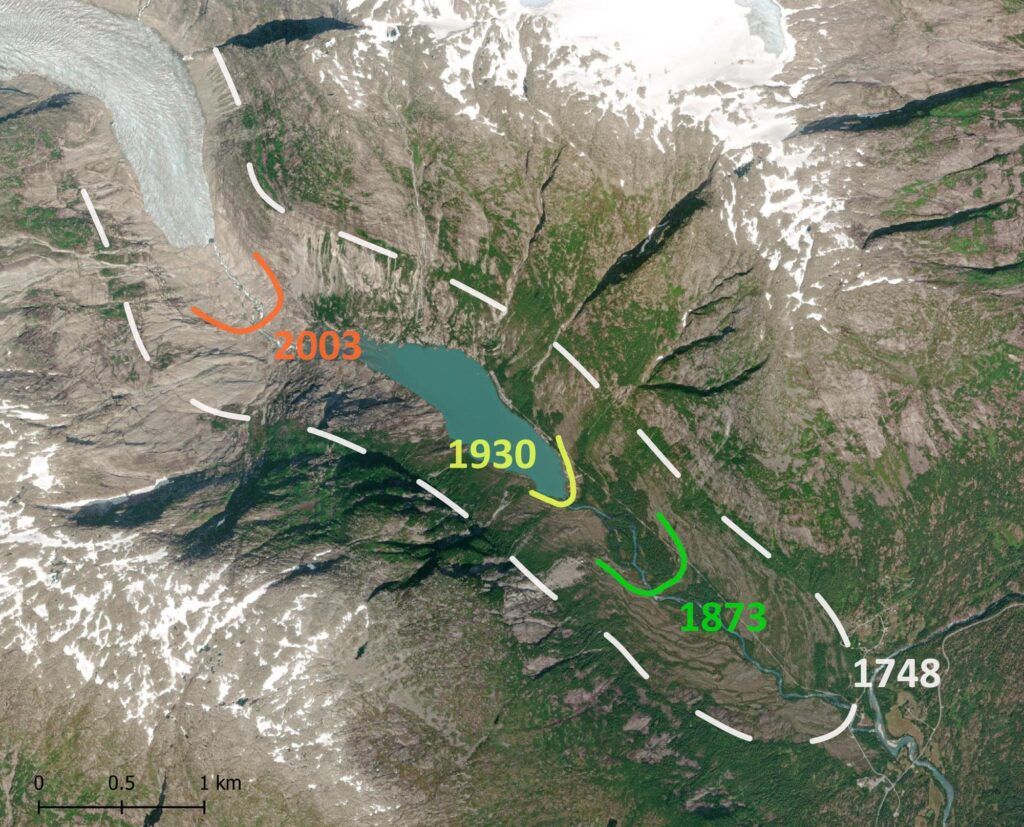

On its way down, Nigardsbreen overran a tree around 1680. The tree stump remained in place and was found in 2005, not far from the glacier front. The pine tree grew at the western end of lake Nigardsbrevatnet, which is over 4 km from the furthest point the glacier reached in 1748. That means the glacier advanced 4 km in less than 70 years (Nesje et al., 2008).

The year of Nigardsbreen’s maximum extent (1748) is precisely known thanks to the local vicar Matthias Foss. He wrote down how the glacier wreaked havoc upon his community and slowly started retreating from 1748 onwards (Foss, 1750). By then the glacier had advanced all the way up to the meltwater river of Jostedalen (Jostedøla).

Moraines, paintings and photographs tell us how the glacier retreated throughout the 19th century (Nussbaumer et al., 2011). Occasionally it had small advances, leading to moraine ridges. Then, John Rekstad started length change measurements in 1899. He initiated a project that still exists today and which gives a detailed image of Nigardsbreen’s behavior.

Nigardsbreen in 1880-1890 and 2024. Source 1880: Axel Lindahl, National Library URN_NBN_no-nb_foto_NF_WL_02530.

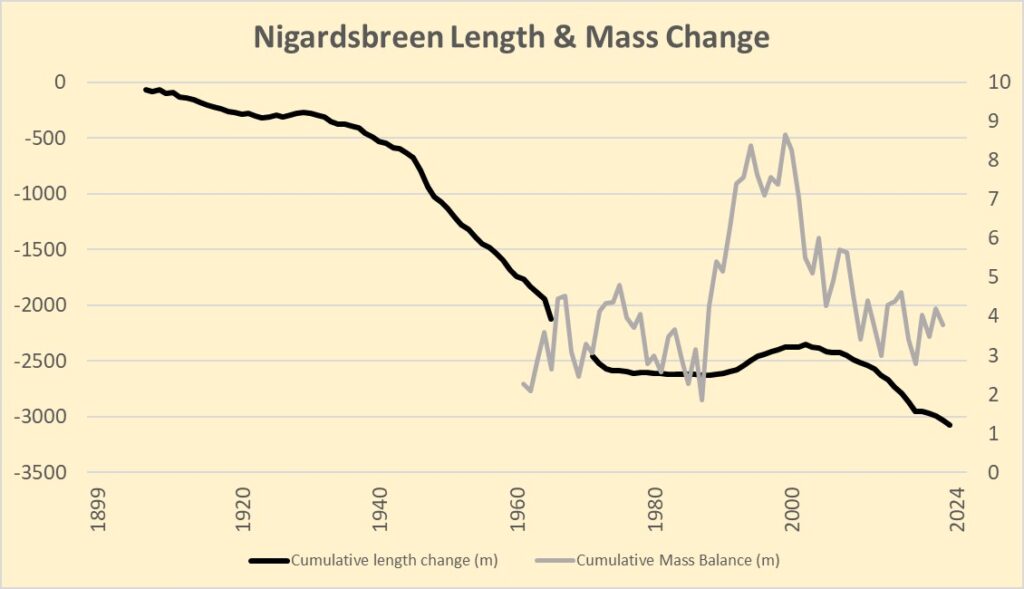

For the first fifty years of length change measurements, Nigardsbreen slowly retreated. In the 1940’s and 1950’s the glacier lost more length, because it calved into lake Nigardsbrevatnet. Around 1976 recession abruptly stopped and from 1990 onwards the glacier advances. By 2003 the glacier had readvances 250 m, after which it has been in continuous retreat (NVE).

Length change is linked to mass balance, which is the difference between melt in summer and accumulation in winter. If a glacier is getting thinner, less ice flows to the snout, thus it recedes. And vice versa: a thickening glacier leads to advance, exactly what happened with Nigardsbreen around 1990. Remarkably, there was no net loss since 1962, when mass balance measurements started (data: NVE).

The recession of Nigardsbreen is not accompanied by net mass loss, in contrast to all other Norwegian glaciers. Massive thinning of the relatively small snout is counterbalanced by minor thickening at the much larger upper levels (Kjøllmoen, 2022). This might eventually slow down recession, although mass balance measurements are notoriously difficult. Summer melt is often a little underestimated, while snowfall is overestimated (Andreassen et al., 2016).

Normally, a retreating glacier doesn’t receive much attention. After all, what’s new? But Nigardsbreen is a special case. As one of the biggest and lowest glaciers, it is a must-see for Norwegians and tourists alike. Many people take their first ‘glacier-steps’ here. But the hike to the glacier is getting longer and longer.

Breheimsenteret with Nigardsbreen in ca. 2000 and 2024.

In 1993, a characteristic visitor center resembling a crevasse was built close to the 1748 moraine. This ‘Breheimsenteret’ (glacier center) burned down in 2011, but was rebuilt within two years. Its souterrain hosts a permanent exhibition about the history of Jostedalen in general and Nigardsbreen in particular.

Nigardsbreen above Nigardsbrevatnet in 1998 (Rudiger Stehn via Flickr) and 2024.

Although the visitor center is separated from the glacier by 4 km of gravel plains, bushes, moraines (and a lake), the ice used to be clearly visible. However, Nigardsbreen is about to get out of sight because of continues thinning and retreat over the past 20 years.

Once Nigardsbreen goes around the corner, you’ll need to walk to the snout in order to see ice at all. A road leads up to lake Nigardsbrevatnet, where a large parking lot serves as the starting point for glacier walks. But it’s another 2 km of slippery rocks to the front of the glacier.

Well, at least nobody goes to bed hungry anymore because of Nigardsbreen.

Search within glacierchange: