Claridenfirn is a mountain glacier in central Switserland. It sits high up the mountains and doesn’t have a clear snout. Instead, it partially falls over a cliff. Though beautiful, this complicates its exceptional long mass balance record.

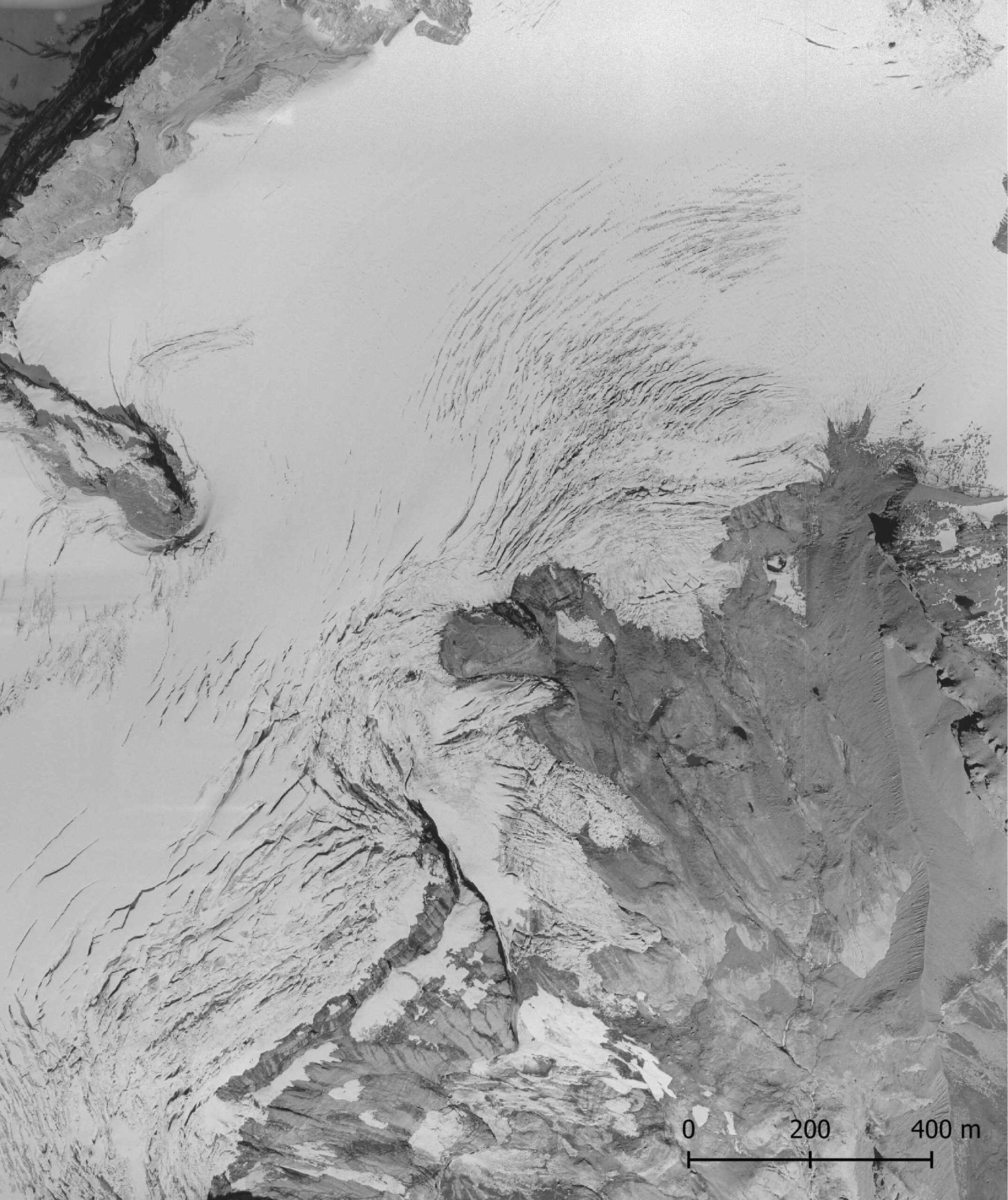

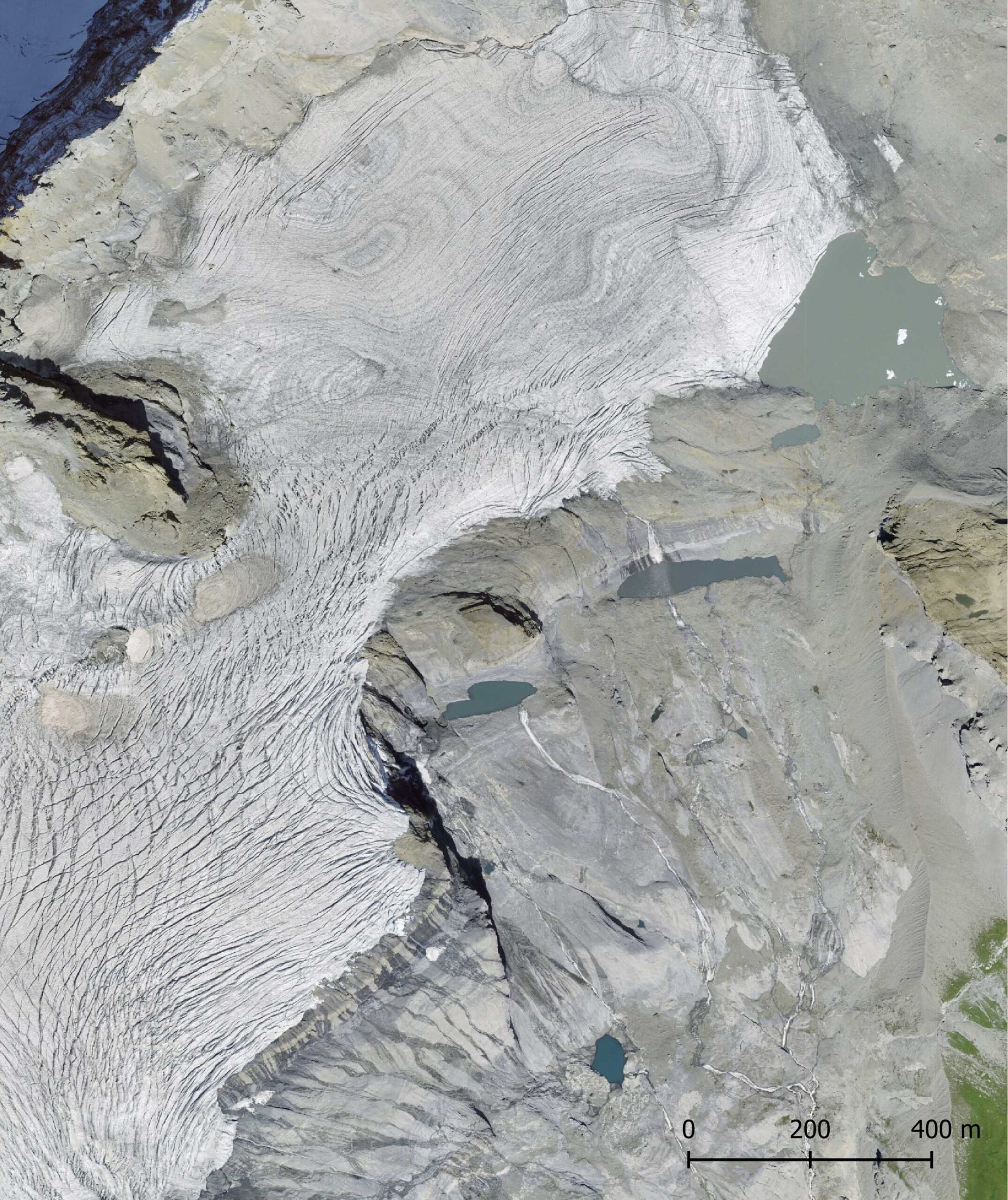

Orthophoto of Claridenfirn in 1990 (left) and 2022. The cliff is bottom-image. Source: swisstopo Zeitreise.

Claridenfirn consists actually of three more or less separated glaciers. The western part has an ice thickness up to 200 m, a flow velocity of 13 m a year and ends as an ice cliff above a 500 m steep cliff. The eastern part is much smaller and terminates in a proglacial lake with some small ice bergs. The southern part has its own name (Spitzalpelifiren), but is not very interesting.

Mass balance measurements started at Claridenfirn in 1914 and have been conducted ever since. No other glacier in the world has such a long record (of good quality). Since 1914, two point measurements have been carried out at 2900 m above sea level (western part) and 2700 m (eastern part). The upper site always experienced mass gain (more snowfall then melt), the lower site is losing mass since the 1980’s.

The exceptionally long mass balance time series reveals initial mass increase. In fact, in the early days snow depth was sometimes so extreme that the mass balance stakes were lost! Snow thickness is unknown for these years. Nevertheless, it is clear that Claridenfirn melted more in the 1940’s and especially since the 1990’s. The duration of the melt season increased by nearly a month. At the same time, winter mass gain (snowfall) has stayed more or less the same (Huss et al., 2021).

Some data is missing, but luckily snow depth isn’t the only thing Swiss like to measure. The first accurate map of the area was already produced in 1936. Its (height) contours could be transformed into a Digital Elevation Model (DEM), which can be compared to later DEM’s from new maps, aerial photos and direct elevation measurements. This way, one can see changes in elevation, thus revealing glacial thinning or thickening. Together with meteorological data, the DEM’s help to check mass balance measurements and extrapolate them to the entire surface of Claridenfirn.

To make things a bit more complicating, the ice cliff of western Claridenfirn adds to the mass loss. After all, ice that breaks off from the glacier and falls down means losing ice, without any melt. Because this can’t be measured by stakes, scientists have estimated it based on the flow velocity and ice thickness. They concluded that frontal break-off accounts for nearly a tenth of total mass loss over the entire period, peaking at 20 percent annual loss in the 1980’s. So for every four liters of meltwater, an additional kilo of ice broke off in those days (Huss et al., 2021). Below the cliff a small regenerated glacier existed.

The measurements also show that the glacier thinned by 24 m between 1916 and 2020. But it didn’t took 106 years to melt that much ice. The mass loss in the 1940’s was compensated by mass gain before and after, so that the glacier had the same size in the 1980’s as in 1914. All thinning occurred since then and has reduced calving to a minimum. The ice cliff has become too thin to really cause ice loss of any significance.

The scientific paper on Claridenfirn was published in 2021. The authors found a strong increase in glacial thinning, but they could never have imagined what would happen in subsequent years. After a dry winter, lots of Sahara dust (lowering reflectivity) and a scorching summer, Swiss glaciers lost record-breaking amounts of ice in 2022. Claridenfirn thinned with 3 m (averaged out over its entire surface), three times more than the 2010-2020 average. 2023 wasn’t easy on the glacier either, with -2 m.

Melt has led the calving front to practically stop functioning in the upper part of Claridenfirn. In the lower part the glacier is both thinning and receding, which has resulted in the formation of a proglacial lake. The glacier is calving a little bit into it and produces small icebergs. In this way, the extreme melt of the past decades has not only stopped the glacier to calve above a cliff, but created a new calving front as well. For now: once an ice dam melts away, the lake will probably fully drain.

Search within glacierchange: