Austdalsbreen is a five km long glacier in the north of Jostedalsbreen ice cap. The glacier has by far the biggest calving front in southern Norway and this even increased after the construction of a reservoir in front of the glacier.

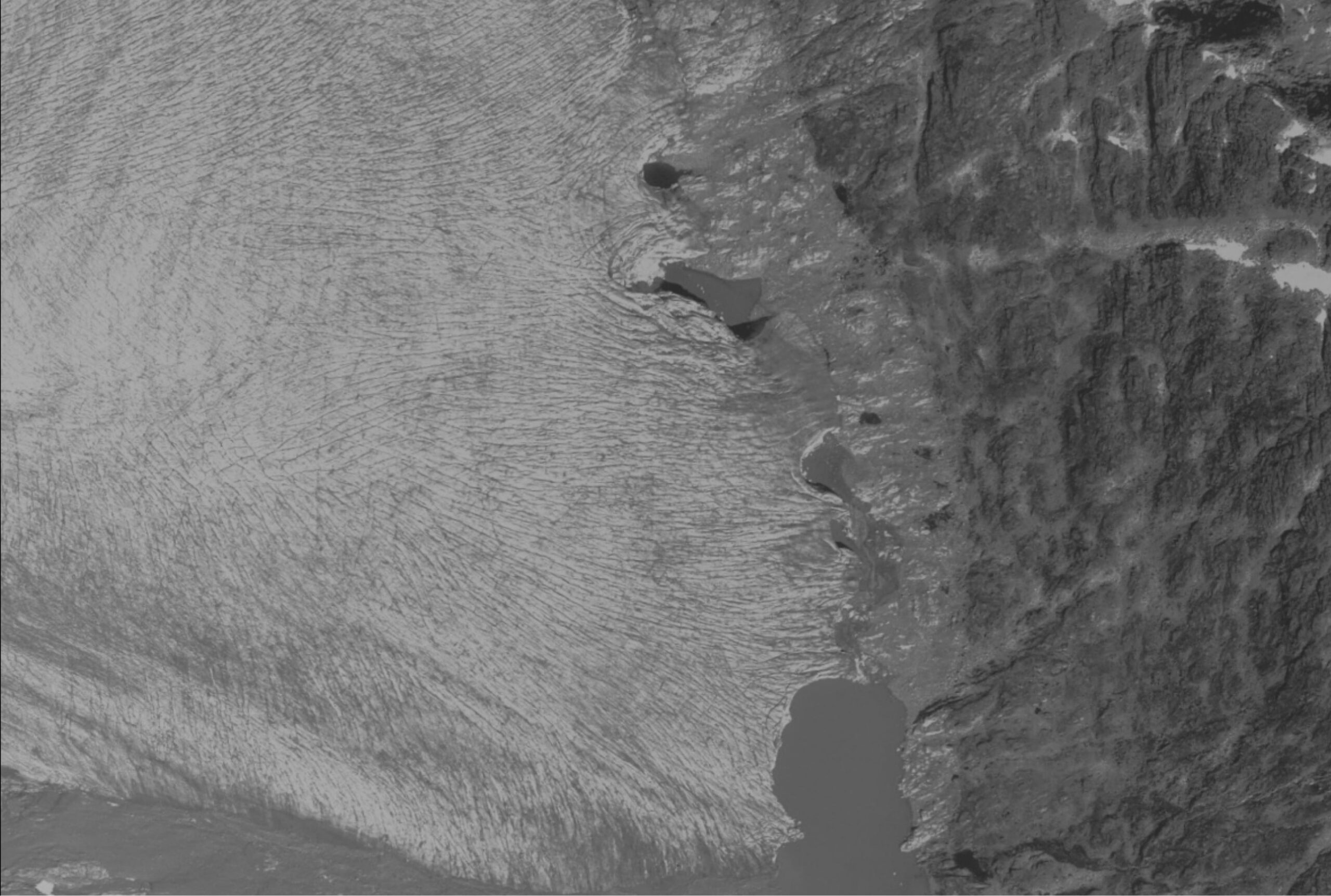

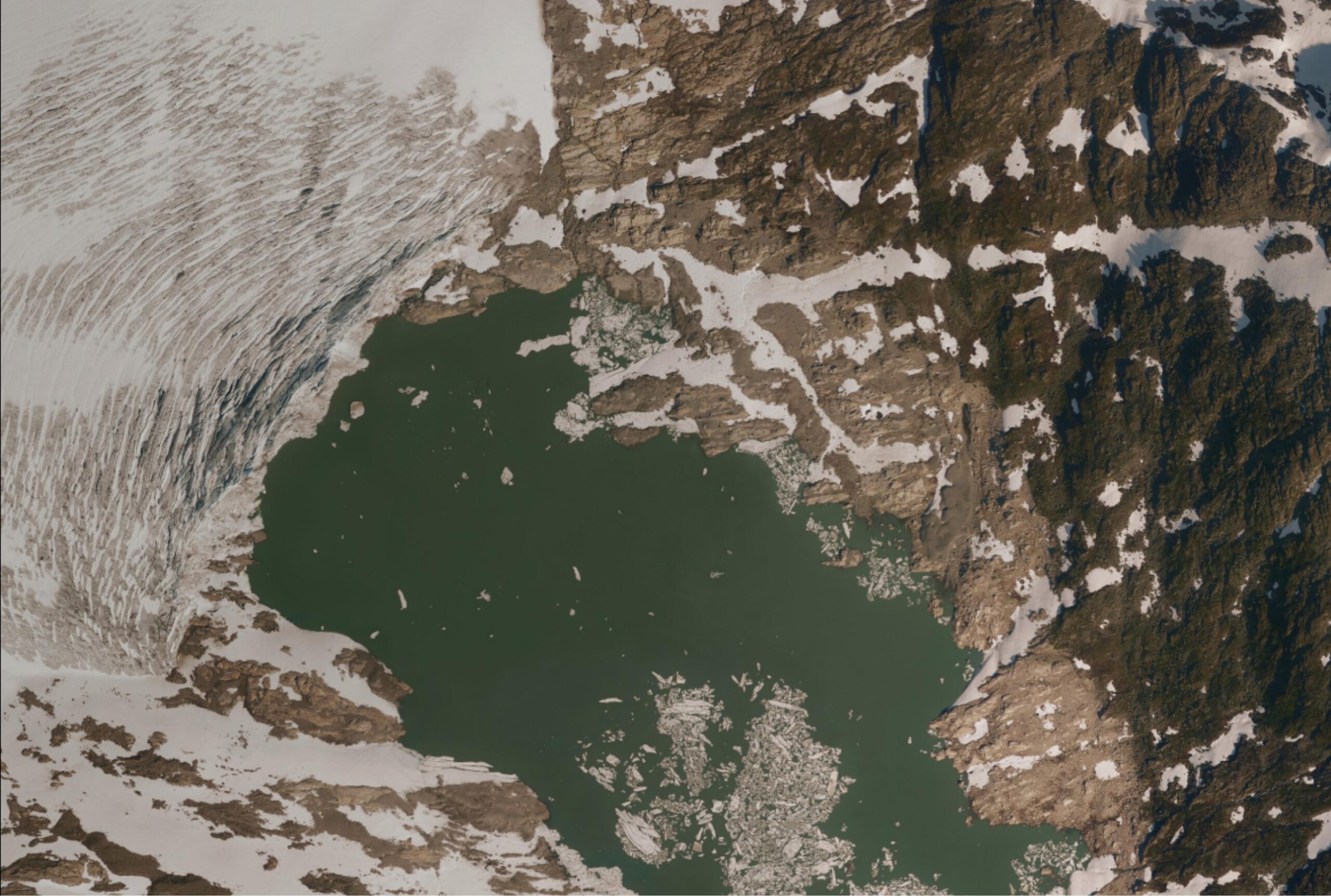

Austdalsbreen in 1966 (left) and 2015. Source: norgeibilder.no.

Before the construction of the dam in 1988, Austdalsbreen was already in decline. The glacier lost an estimated 10 m in thickness and 100 m in length over the period 1966-1988. This was in part due to calving, as Austdalsbreen already terminated into a natural lake (Austdalsvatnet, 1157 m a.s.l.) that was later transformed into a reservoir.

After 1988 the maximum water level in the lake was raised by forty meters and varies since then between 1140 and 1200 m, because the water is used for hydroelectric power. In spring, the snout doesn’t touch the water, because the lake is drained for hydroelectricity in winter. During summer the lake level rises again thanks to melting snow (and glaciers!), so Austdalsbreen terminates in the water.

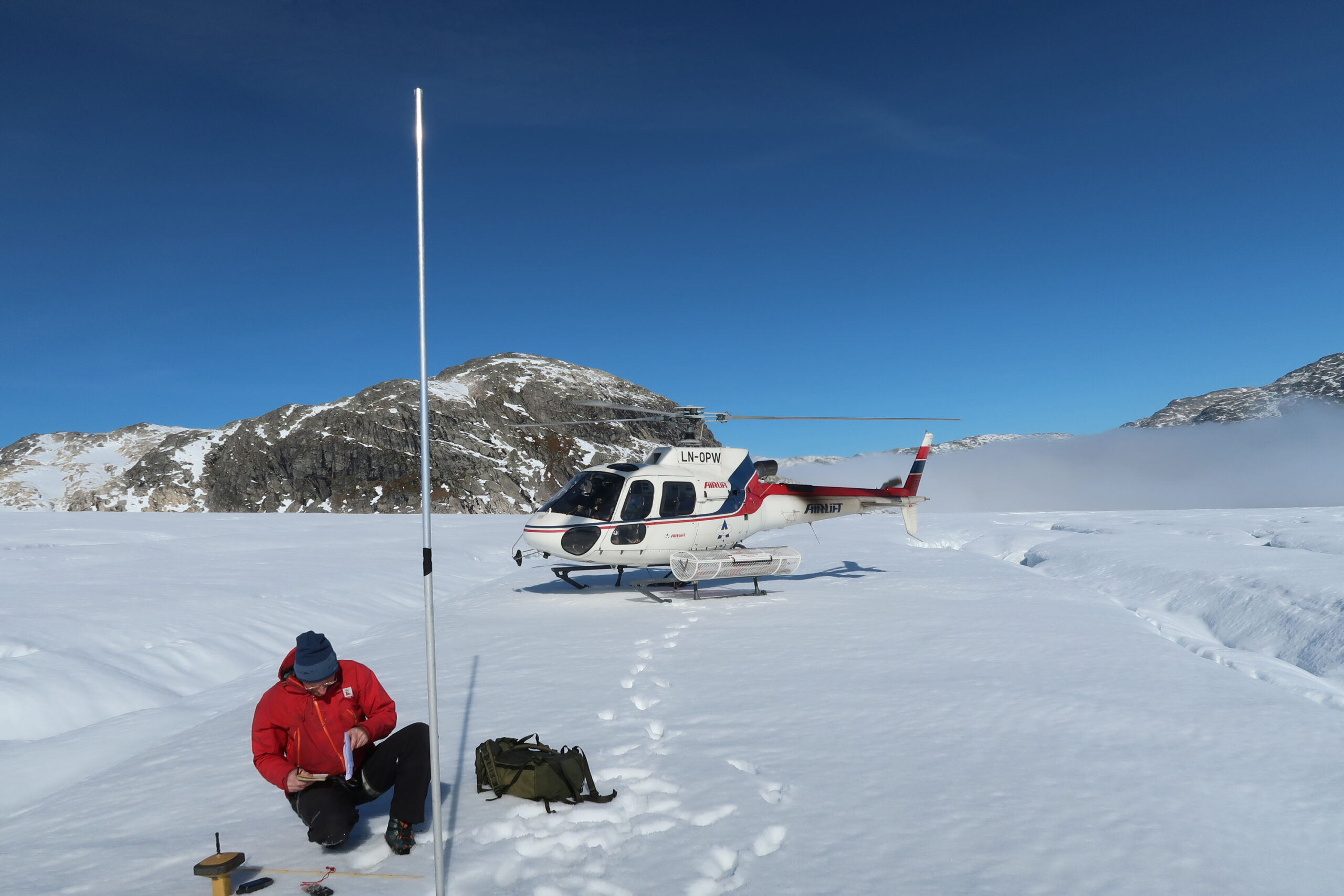

The Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Administration (NVE), responsible for both glacier monitoring and (hydroelectric) power, already expected the glacier to respond to the change of water level and started to monitor Austdalsbreen more closely. The bed topography, glacier velocity and mass balance were investigated. The glacier is up to 300 m thick and covers a flat and broad valley (NVE, 1990).

Just before Austdalsvatnet became a reservoir, stakes were drilled into Austdalsbreen to measure its flow velocity. In the beginning, the glacier snout moved seven centimeters a day (or 25 m yearly). As soon as the water level rose the glacier picked up speed, because water creeped underneath the glacier and reduced friction. Also, the glacier started to float partially. Sliding velocity doubled to 13 cm per day or 50 m a year (Laumann and Wold, 1992). This increased speed would lead the glacier terminus to advance, if it wasn’t for calving: at the same time as velocity increased, calving rates did too.

The combination of increased velocity and calving rate was expected to result in 500 m of retreat within the first ten years after 1988 (Hooke et al., 1989). Indeed, the front of Austdalsbreen retreated swiftly over the first few years after inundation. But the rise in lake level happened to coincide with the start of a period of positive mass balances, meaning that the glacier received more snow than was melted. In these years the lake often stayed frozen well into summer, which decreased calving at Austdalsbreen. After ten years the length change was 320 meters, a bit less than projected.

At the start of the hydropower project, the effect of greenhouse gases on the earth’s climate was already widely recognized. So with respect to the future behavior of Austdalsbreen, researchers at NVE also projected length chance as the combined effect of rising temperatures and increased calving (Laumann and Wold, 1992). The estimated retreat of 1 km by 2040 is comparable to the actual retreat of 700 m over the 1988-2022 period (based on the yearly NVE Reports). Quite the achievement.

Even though Austdalsbreen is melting quite fast, the glacier is still impressive. Its calving front is close to a kilometer wide and forty meters high (Andreassen et al., 2023). But this won’t last forever. The bedrock underneath the glacier rises eventually above the maximum lake level. After decades of strong retreat, the glacier terminus is now getting very close to this point. Not only is the lake getting more narrow as a result, the retreat of the glacier also decreased considerably over the last four years. In fact, in the 2019-2022 period the frontal position was stable for the first time since measurements began in 1988! This could indicate that the snout lies on bedrock so high, that it’s hardly affected by the water (and therefore calving) anymore.

But even though mass loss through calving is decreasing, Austdalsbreen keeps melting from above. A rare form of ablation (calving) is thus being replaced by a very common one (melt). Bad luck for everyone wanting to get a taste of Svalbard in southern Norway.

Search within glacierchange: