Axarfellsjökull is a glacier in the far east of the Vatnajökull ice cap. It lies in Lónsöræfi district, known for its pristine nature.

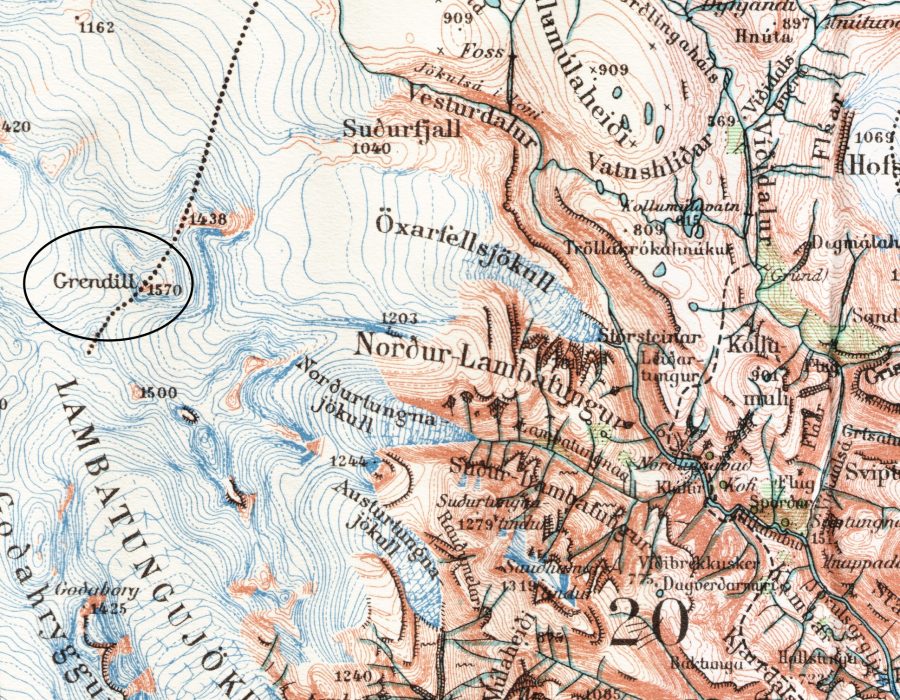

Axarfellsjökull (Öxarfellsjökull) is 10 km long and starts at 1500 m above sea level. There, a few small mountains peep through the ice. On a map that was made in the 1930’s, one of these nunataks is named Grendill (1570 m). Because this is an uncommon name in Iceland, Icelandic linguist and historian Stefán Einarsson dedicated some time to this remote nunatak. Is the name connected to old saga’s, the settlement of Iceland or just a modern name?

Einarsson found the name on a map that was produced by the Danish mapping expedition in the 1930’s. The highlands of East Iceland were surveyed by Steinþor Sigurðsson in 1930-1938. But because he was killed by the eruption of Hekla volcano in 1947, Einarsson couldn’t ask him where he got the name Grendill from. He did discover that the surveyor was assisted by a local farmer for some time. This Jón Sigfússon lived at Bragðavellir farm and could be the key to unraveling the mystery of Grendill.

Jón Sigfússon lived at Bragðavellir. In 1905, he found the very first Roman coin in Iceland, close to his farm. The site had mostly Viking Age structures and artefacts, but Jón nevertheless found a second Roman coin in 1933. Both date from the third century. In later years, four more Roman coins were found in Iceland, of which two are dismissed because they are probably deliberately planted at excavation sites to create a hoax (Heiðarsson, 2010).

The discovery of Roman coins contested the general idea that Iceland was first settled around 870. It also sparked new interest in the story of Pytheas of Massila, a Greek from Marseille that lived in the 4th century BCE. He wrote an account of his great voyage over the northern seas in which he described seeing land in a congealed or sluggish sea. He may have seen Iceland in icy waters and called it Thule (Hansley, 2019).

Could Roman sailors have visited Iceland already in the third century? Did they know about the mysterious land called Thule? And is there a connection to the uncommon name Grendill? Probably not. Despite theories of an archeologist and later president of Iceland that a Roman ship veered off course in stormy weather and ended up in Iceland, most evidence points towards the Vikings. They would have brought old coins to Iceland during their settlement (Heiðarsson, 2010).

Jón Sigfússon, the farmer of Bragðavellir who found two Roman coins at his farm, may have had an explanation for the name of the mountain at the top of Axarfellsjökull. But when Einarsson visited Bragðavellir, the farmer already died. He was survived by his two deaf-mute children, with whom the secret of Grendill was well-kept (Einarsson, 1956). Luckily, the mysterious name is still used on modern maps.

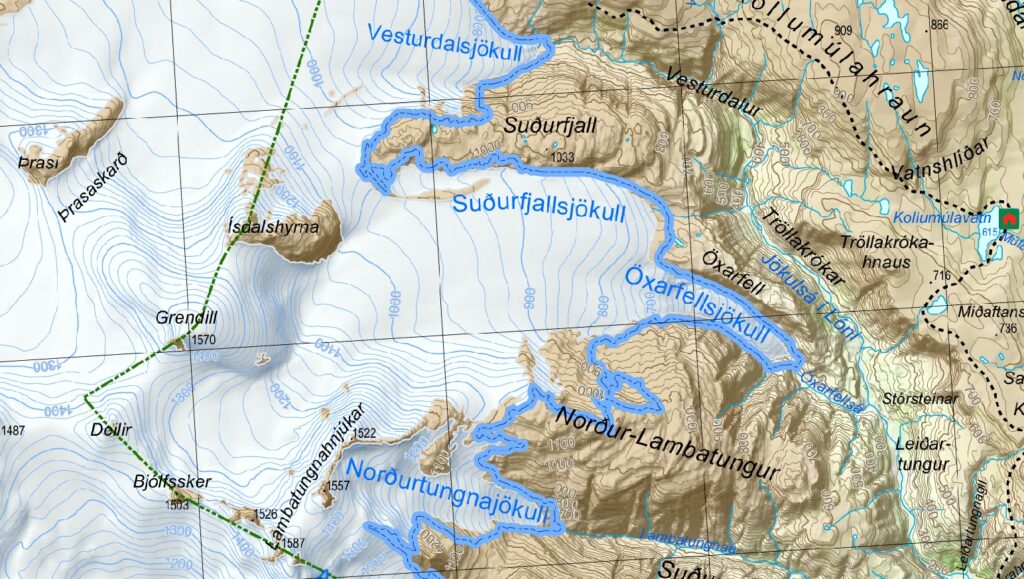

Axarfellsjökull descends from Grendill to the east as a 2 km wide glacier. So wide, that the northern part even bears its own name (Suðurfjallsjökull) and formed a secondary snout during the 19th century. But the bottom 2 km of the glacier plunges into a confined valley and is very narrow. At present, Axarfellsjökull terminates at 400 m above sea level, but it is shrinking fast.

Axarfellsjökull in 1935-1940 (left) and 2023. Photograph 1935: Steinþór Sigurðsson, Jöklarannsóknafélag Íslands.

Visiting Axarfellsjökull requires a demanding, yet rewarding hike. The glacier is namely located in Lónsöræfi (also known as Stafafellsfjöll), a wilderness area. The only road providing access to the area fords Skyndidalsá and runs up Illikambur ridge. Hikers can alternatively follow the left bank of Jökulsá river and cross it via an impressive footbridge. It was built in 2004 and opens up a spectacular route. After many miles the path joins the road at Illikambur.

From the northern tip of Illikambur, the Múlaskáli mountain hut is visible on the other side of the Jökulsá river. It is located near a narrow part of the powerful river, where people already crossed it with ropes in the 19th century. Back then, some farmers tried to make a living in the area, without much success. In the 20th century farmers only herded their sheep here and they constructed a first footbridge in 1953, which collapsed and was replaced in 1967. That bridge withstood the fierce Icelandic weather until 2018, when a winter storm destroyed it. The present bridge was installed in 2019 (mbl.is, 03-07-2019).

On the other side of the river lies Múlaskáli hut. From there, multiple routes bring you mountain peaks, ravines and other huts. Two paths climb out of the valley and go north, to Egílssel and Geldingafell huts. On their way they pass the Tröllakrókar cliffs, which provide a good view over Axarfellsjökull.

Despite new bridges and the presence of multiple huts in the area, Lónsöræfi remains a quiet area. Those who do go here, are hikers that praise the area for its lack of facilities and infrastructure. Compared to other nature destinations in Iceland, the hikers are more often Icelanders instead of foreigners. There has been some debate about whether the area should be opened up by building more bridges and other infrastructure, but so far Lónsöræfi has remained a primitive hikers paradise (Sæþórsdóttir, 2010).

Search within glacierchange: