Glacier de Bionnassay (Bionnassay Glacier) is a glacier in the west of the Mont Blanc massif. Here, a fatal flood started and an ambitious railway project ended.

The glacier is named after the small village of Bionnassay at 1300 m a.s.l. In the 19th century, the glacier front was only 1.5 km from the village. At the end of a period called the Little Ice Age (1200-1850), Glacier de Bionnassay reached down to 1700 m and was about 6 km long.

Although the glacier thinned and receded a bit since then, no dramatic changes occurred in the course of the 20th century. Around the year 2000, the debris-covered snout still reached down to 1800 m and had only receded by a few hundred metres. It thinned considerably though.

A nearby glacier has a much more violent history. Directly north of Bionnassay Glacier lies the much smaller Tête Rousse Glacier. In 1892, a subglacial lake from it drained, blowing a hole in the snout and releasing 200.000 m3 of water. The flood carried with it mud, boulders and ice and devastated the villages of Bionnay and Le Fayet, and the bathhouse (spa) of Saint-Gervais. 175 people were killed by the night flood.

The ‘Catastrophy of Saint-Gervais’ triggered research into such hazards in general and the cause of the flood in particular. At first, two crevasse-born cavities were believed to have caused the flood. However, a more recent study concluded that the upper reservoir actually started as a lake on the glacier surface that was later hidden by new snow and ice (Vincent et al., 2010). Tête Rousse Glacier still has cavities, so in theory it could unleash a new flood (Guillemot et al., 2024).

The flood path included parts of Bionnassay Glacier, but the event didn’t affect the glacier. Climate change does. Since the start of the 21th century, the glacier experiences rapid melt. In front of the downwasting snout a lake appeared that is growing larger ever since. And in 2018, the snout became detached from the rest of the glacier at a steep part of the icefall at 2000 m. Within a few years the same will happen a little higher up the icefall at 2400 m.

French glaciologist Luc Moreau illustrates the movement and melt of glaciers with the help of timelapse cameras. In 2009, he installed a camera on the northern lateral moraine of Bionnassay glacier at an altitude of almost 2600 m. It is pointed towards a steep section of the icefall and registers the continuous sliding of the ice and serac formation and collapse. See a clip at https://dai.ly/xp7xas.

Visiting Bionnassay Glacier can be both hard and easy. The hard, though most rewarding way is by walking from the valley floor to Refuge du Nid d’Aigle (2390) or even Refuge de T te Rousse (3170). The latter mountain hut is large, as it is part of the normal route to the top of Mont Blanc. After T te Rousse, hiking booths have to be changed for climbing gear.

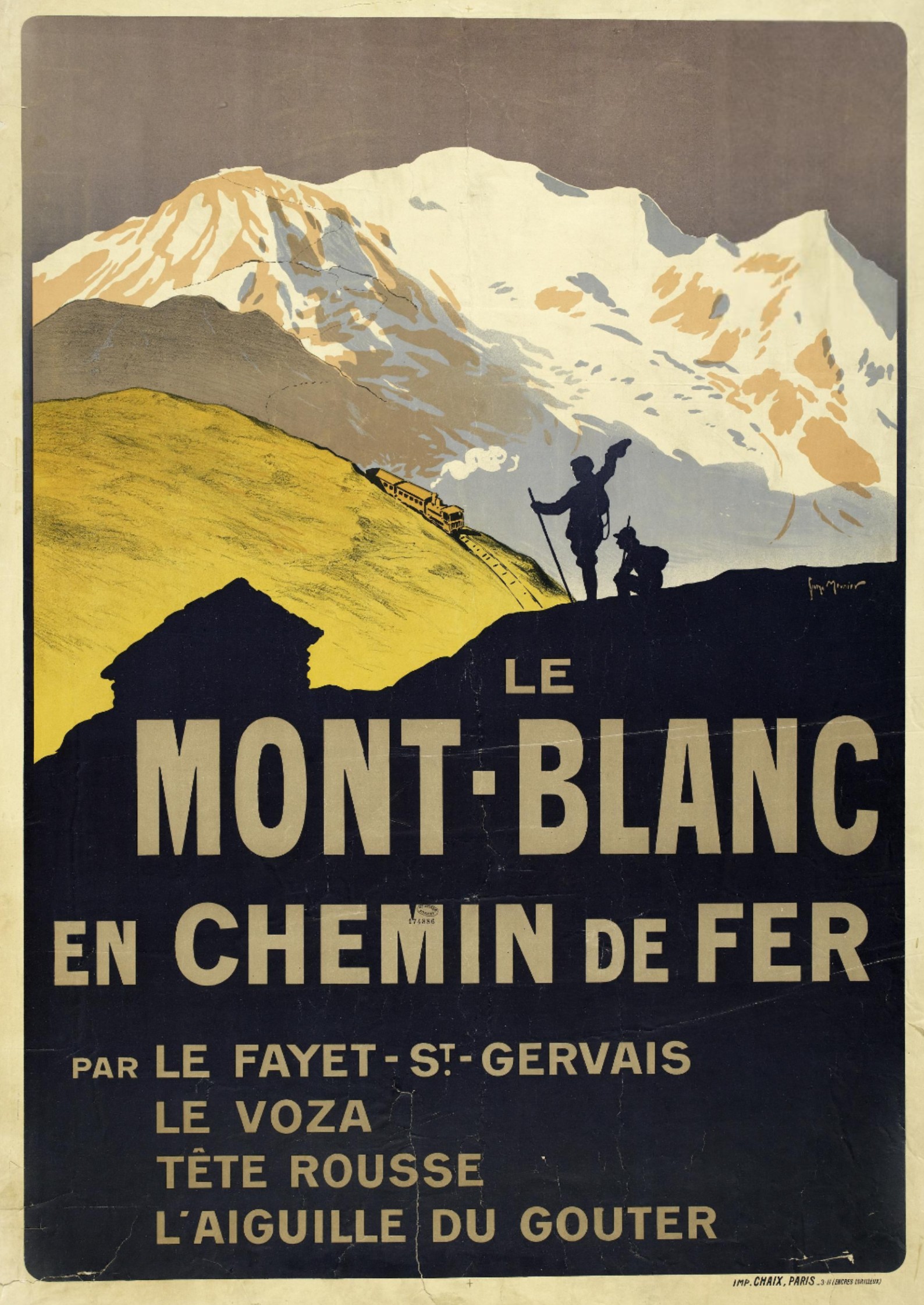

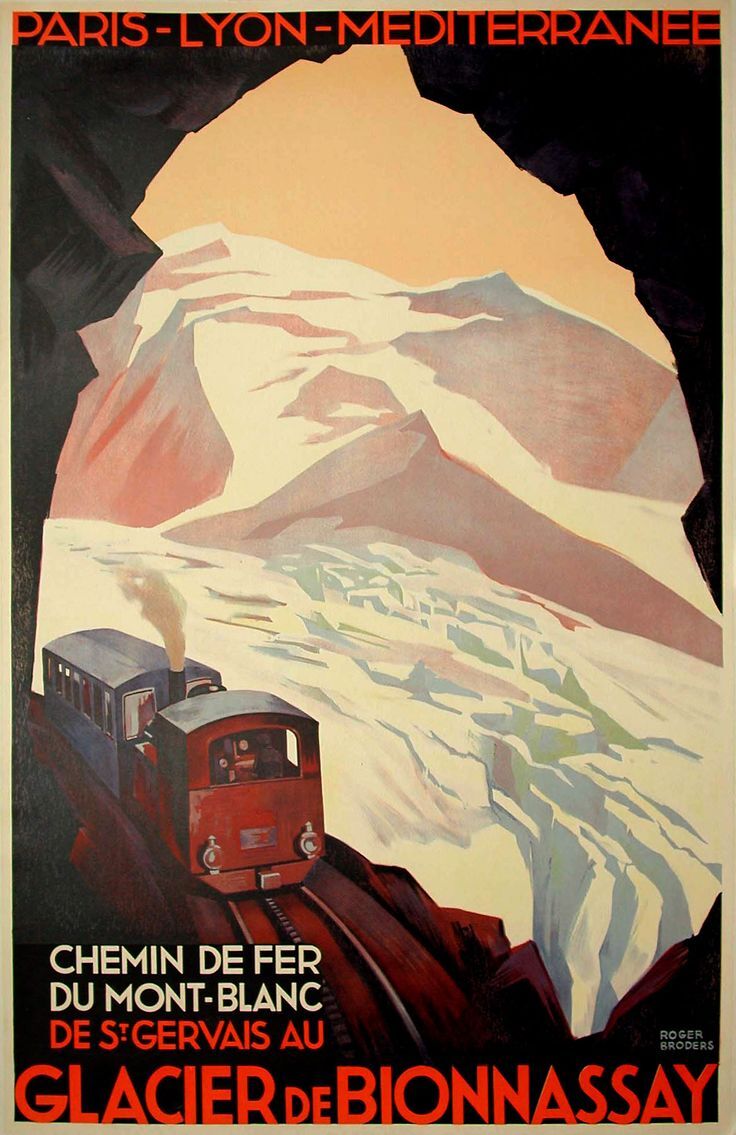

Alternatively, you can go the easy way and buy a ticket for the Mont Blanc Tramway, the highest railway line in France. It brings you to Nid d’Aigle station close to the mountain hut. When it was built, engineers dreamed of reaching the much higher Aiguille du Goûter (3860 m), but construction stopped when the first World War broke out in 1914. Without the war, climbing Europe’s highest mountain would have been a walk in the park!

Search within glacierchange: