Briksdalsbreen is a popular glacier arm of Jostedalsbreen that advanced spectacularly in the 1990’s. But glacier tourists are in for a disappointment.

Briksdalsbreen is a steep and relatively short outlet glacier in the west of Jostedalsbreen. It plunges down from the ice cap. In just over 2 km it descends from an altitude of 1600 m to 550 m. The snout hangs 200 m above a lake in which it terminated for a long time. The blue ice in the mountain lake was a true attraction, but ceased to exist in 2010 when the glacier retreated from the lake.

Although the icebergs have disappeared, many tourists still make their way to the lake. In fact, special vehicles bring people from the visitor center into Briksdalen valley, a ride that saves you the walk of 1.5 km and 150 m up. Still, please walk if you can. That way you’ll have time to enjoy the waterfalls, woodlands and, last but not least, the old moraines that lay in the valley.

The first and oldest moraine lies just above Kleivafossen, a massive waterfall in Briksdalen. The moraine was deposited around the year 1760 (Pedersen 1976 in Nesje, 2005). Nobody described the advance of Briksdalensbreen in the 17th and 18th century that culminated in this moraine. The reason? The glacier didn’t threated any farms, unlike nearby Brenndalsbreen.

Norwegian meteorologist Christen de Seue was the first to both write about and make a photo of Briksdalsbreen, in 1869. He could hardly retrieve any moraine fragments, as they were largely washed away by the braided meltwater river (De Seue, 1870:18). In 1869 the glacier had already lost 600 m of its length since 1760, but Christen was lucky enough to caught the glacier in a state of readvancement. This led to a new moraine in 1872 that was captured in the same year by the well-known pioneering photographer Knud Knudsen (Nussbaumer et al., 2011).

Briksdalsbreen in 1872 and 2024. Source 1872: Knud Knudsen, Bergen University Library photo ubb-kk-1318-0878.

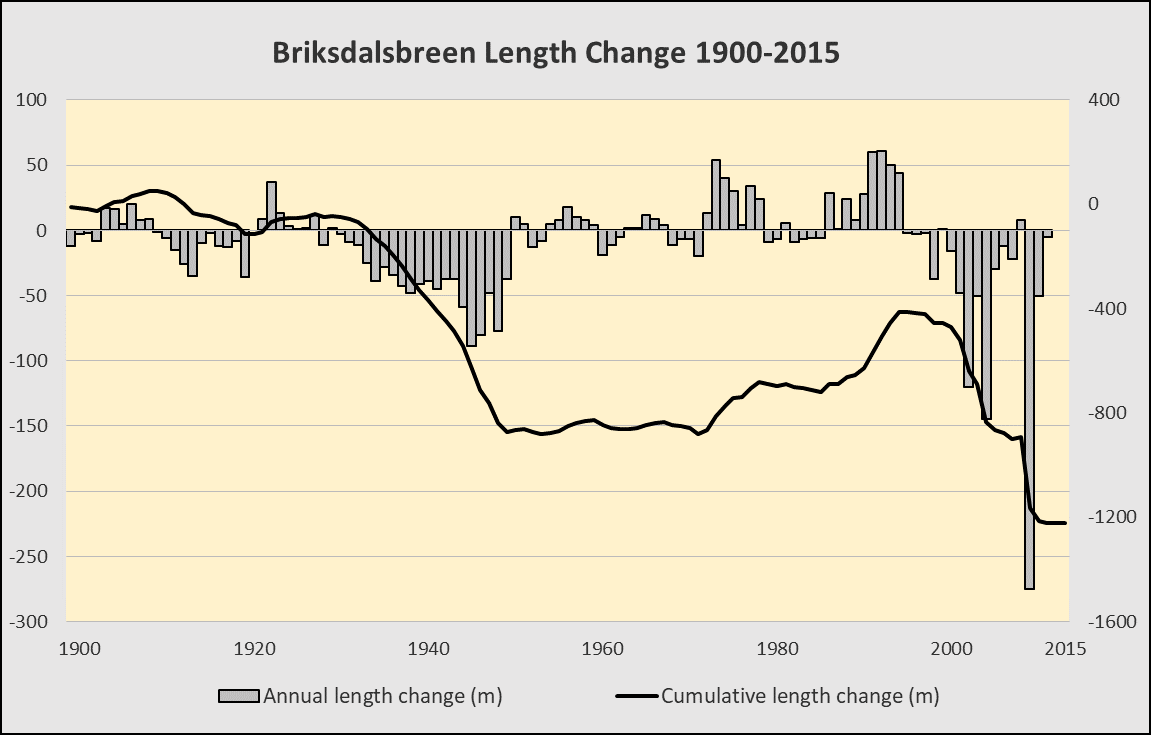

After 1872 Briksdalsbreen had a more or less continuous retreat until 1905, when a six-year period of advance started. By then geologist John Bernhard Rekstad had already started length change measurements, in 1900. For that purpose he engraved a large boulder in front of the glacier. From here, he (and others) measured how far the glacier was from his cross. That worked well as long as the glacier receded. But in 1908 the advancing glacier reached the boulder again. In the following years the huge stone was pushed forward 16 m and turned 180 degrees.

In 1911 Briksdalsbreen retreated again, followed by a new advance between 1923 and 1929. Even though these intermediate advances didn’t quite match the periods of retreat, the glacier only lost 200 m from 1872 to 1934. Then, the climate warmed and all of Jostedalsbreen’s glaciers receded massively. Briksdalsbreen lost 800 m in less than 20 years (data: NVE). By 1952 the glacier barely reached into the lake that was uncovered only a few years before.

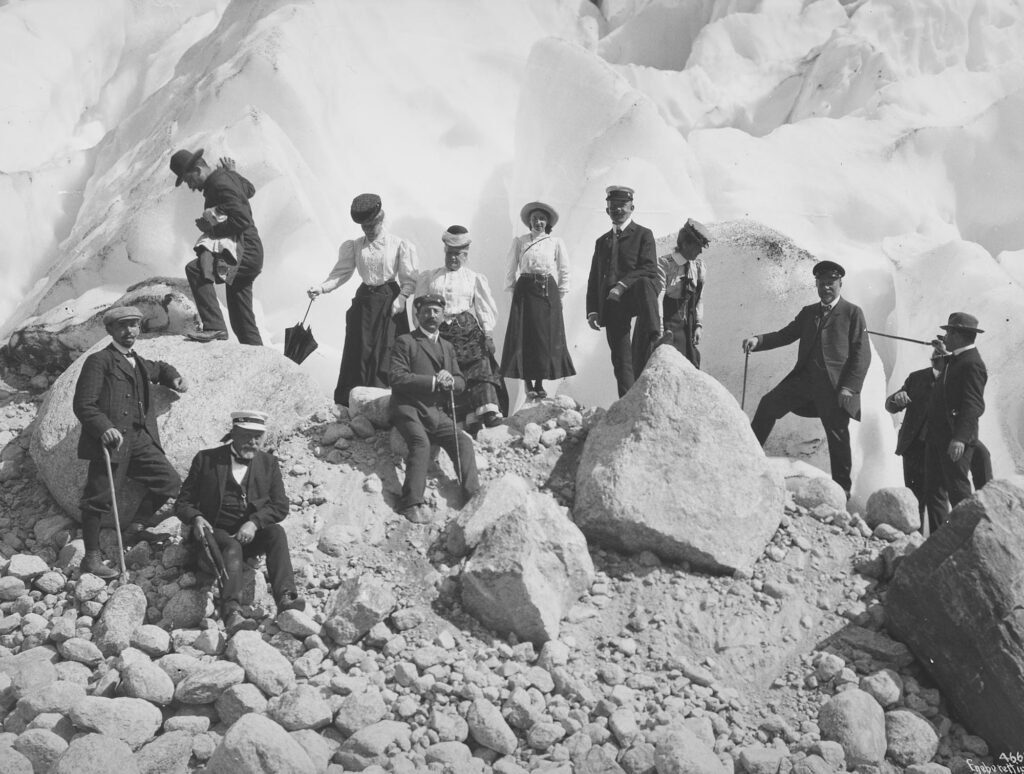

Many people witnessed Briksdalsbreen’s ups and downs. After De Seue, more and more travelers found their way to Oldedalen and its glaciers. They were helped by local farmers, who made a path from the main valley to the glacier in 1880. Nine years later the path was named Kaiser Wilhelm Trail, after the German emperor who visited Briksdalsbreen in 1889. By 1926-1927, up to 1300 people a day would go towards Briksdalsbreen (Eide, 1955).

Briksdalsbreen in 1888 and 2024. Source 1888: Axel lindahl, Geological Survey of Norway Photo Archive NGU001683.

During the 1940’s both visitor numbers and the length of Briksdalsbreen declined. Not long after peace returned to Europe, the glacier also stabilized. In the 1950’s and 1960’s its length stayed more or less the same.

In the mid-1970’s the glacier started to recover. Summer temperatures dropped slightly and snowfall increased. Around 1990 winter precipitation (snowfall) peaked, which accelerated the already advancing glacier. In just four years ( 1993-1996) Briksdalsbreen advanced a massive 278 m. Together with the preceding decades the glacier grew by 450 m and covered almost the entire lake again (Nesje, 2005).

The speed at which Briksdalsbreen grew in the 1990’s amazed glaciologists. Though every western outlet glacier of Jostedalsbreen advanced in response to the increase in snowfall, none of them reacted so vigorously as Briksdalsbreen. In 1994 it grew by 61 m, the largest annual advance ever recorded in Norway since measurements began (Winkler and Nesje, 1999). Second best is an advance of 60 m in 1993, again by Briksdalsbreen!

The increased snowfall in the 1980’s and 1990’s was caused by a dominance of low pressure zones in the North Atlantic, when westerly winds bring mild and humid weather to coastal Norway. Therefore all glaciers along the coast of Norway profited from increased snowfall and advanced in the 1990’s. But because the advance was particularly prominent at Briksdalsbreen, this phase is termed the ‘Briksdalsbre Event’ (Nesje & Matthews, 2012).

The Briksdalsbre Event is not only known for its quick and widespread advance. The subsequent rapid retreat to pre-advance conditions was just as impressive. Again, Briksdalsbreen is a prime example. After holding on to its length until 2001, it lost the same 400 m it had regained in just seven years. In 2007 the glacier had the same length again as in the period 1950-1970. In the following years the ice retreated from the lake, the snout got disconnected and disappeared. This catastrophic break-up was for a large part caused by disintegration in the lake water (Hart et al., 2011). By 2015 only the icefall was left, terminating high above the lake (NVE Glacier Periodic Photo). The length change measurements that were initiated by Rekstad in 1900 had to be discontinued, for the snout has become inaccessible. The glacier will retreat even further in the coming decades (Laumann & Nesje, 2009).

Briksdalsbreen in 2002 and 2024. Source 2002: Clemens Gilles via Flickr.

Surprisingly, Briksdalsbreen keeps attracting flocks of tourists, despite its strong retreat. Maybe they are misled by images displaying a glacier descending well into the lake, maybe they appreciate the landscape with or without a glacier. Either way, it’s an good location to see climate change in action.

Search within glacierchange: