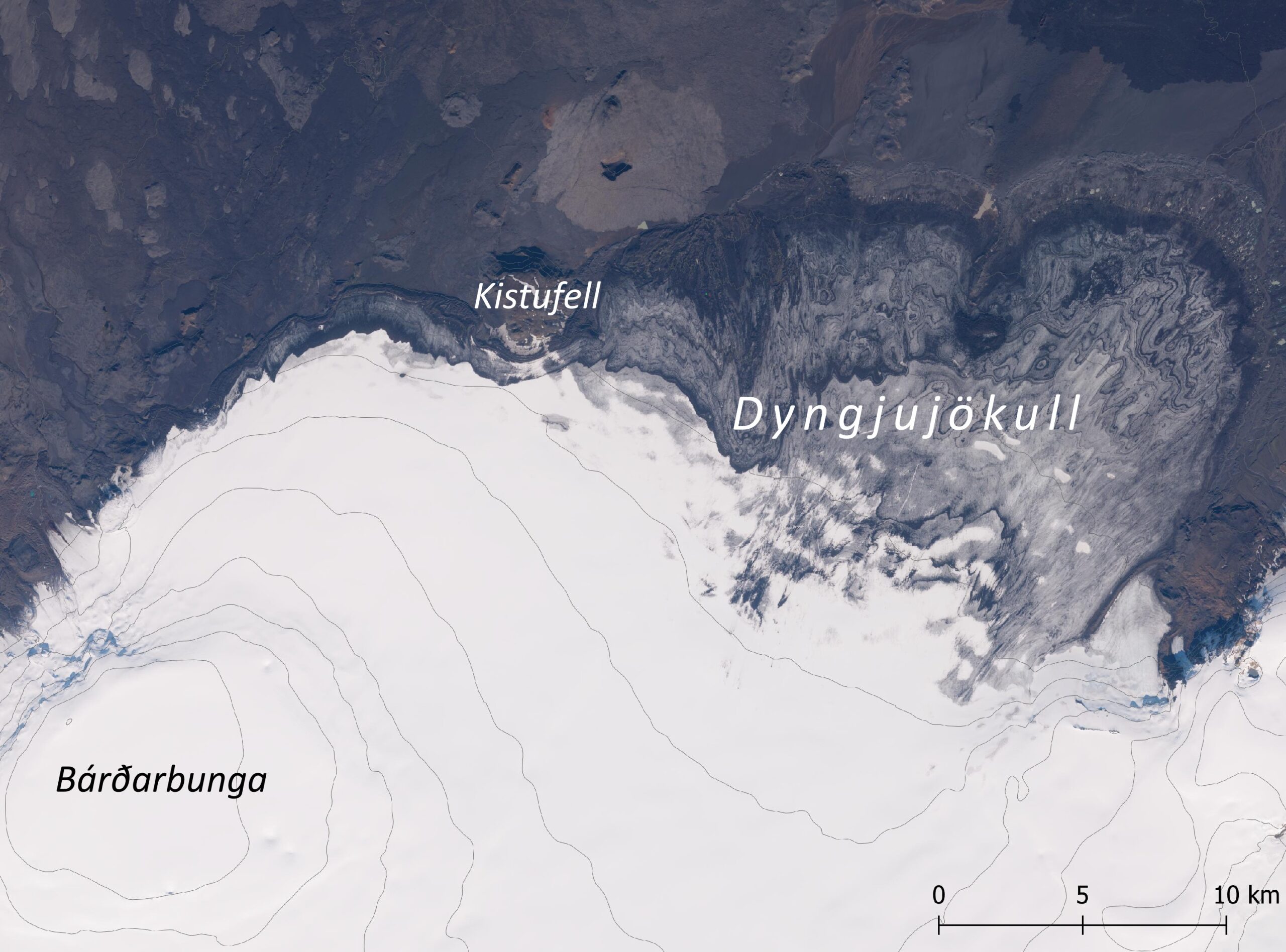

Dyngjujökull is a surge-type glacier in the far northwest of Vatnajökull ice cap. It’s wrapped around Kistufell mountain, which overlooks a unique part of the ice cap.

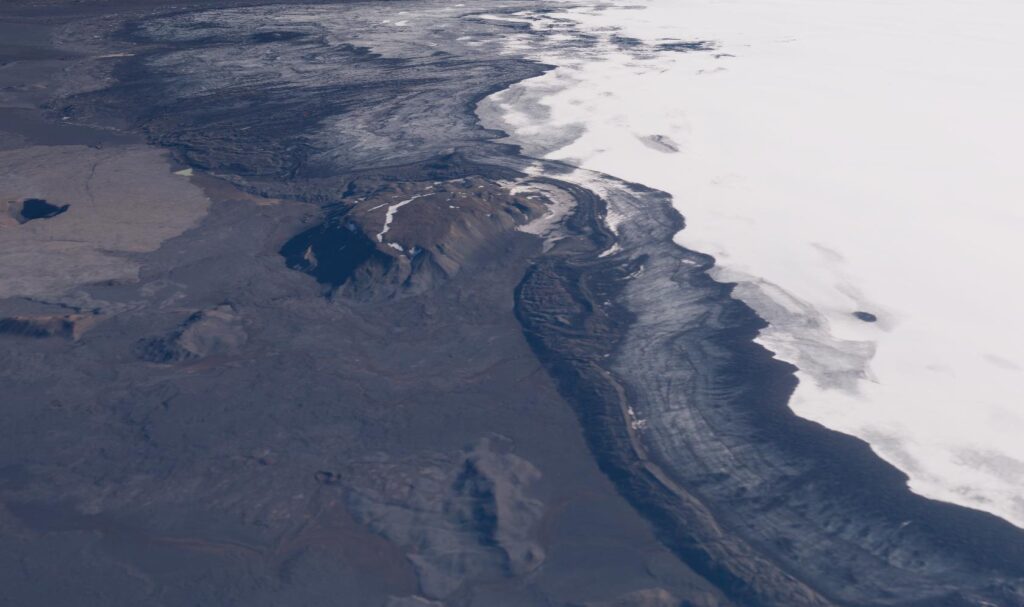

The northern and western glaciers of Vatnajökull differ greatly from those in the south. Instead of temperate valley and mountain glaciers, the ice forms 10 to 20 km broad and flat snouts. In normal times they hardly move, so their surfaces lack crevasses. The glaciers actually share many characteristics with those laying over northwestern Europe during the last ice age (Björnsson, 2017:378).

All of these wide, lobate glaciers with small inclines are so-called surge-type glaciers. They don’t move gradually, but mainly during short-lived events. In a matter of months they advance hundreds or even thousands of metres. When the event is over, the glacier comes to a virtual stillstand again.

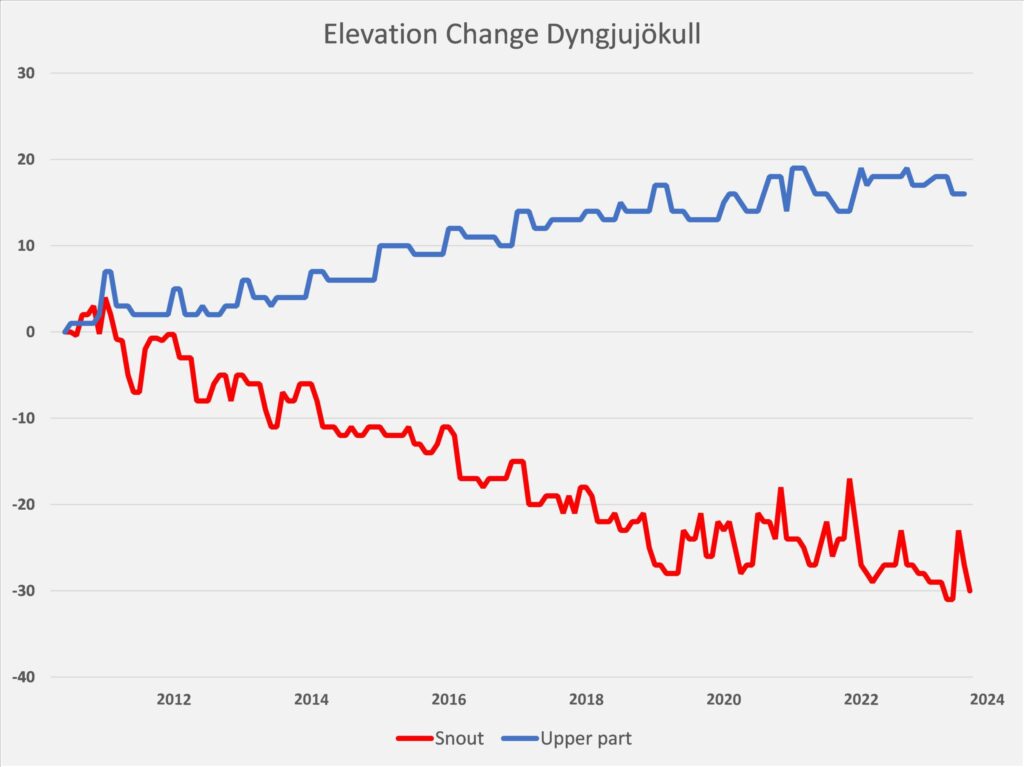

The mechanism behind surge-events is an imbalance in glacier mass. In normal times, the snout thins (melts) and the upper parts or accumulation zone thickens (snow turns into ice). Because of the very small inline, flow velocities aren’t sufficient to compensate these opposite trends. As a result, the glacier’s surface steepens over the course of several decades. Eventually the gravitational force reaches a threshold and pulls the glacier down in a surge event. Ice mass from the accumulation zone flows towards the snout: the upper part thins, while the snout thickens and advances. When the surge is over, the cycle starts over again.

Dynjujökull to the east of mount Kistufell behaves in this way. Since its first recorded surge in 1893, it did so close to every 20 years (Björnsson et al., 2003). The last one occurred in the winter of 1999-2000, when the glacier advanced around 1250 m. This was also the last major surge of any of Vatnajökull’s outlets. In between surges, the surface of Dyngjujökull moves only at a few to 30 m per year (Nasa ITS_LIVE Global Ice Velocities).

Since the turn of the century, not a single Icelandic glacier has surged (apart from a few minor ones in Dranga- and Hofsjökull ice cap). Climate change is to blame. In a warming climate, even the upper parts of the glaciers are not able to amass enough snow to reach their surge-threshold. Luckily, there is one area where Vatnajökull ís thickening: the higher parts of Dyngjujökull, roughly above an altitude of 1300 m. Since satellite measurements began in 2010, the glacier surface has risen by about 15 m. Simultaneously, the margin has lowered by 30 m (data: ESA, CryoTempo Eolis). The gradient of the glacier thus increases and, if sustained, might lead to a new surge.

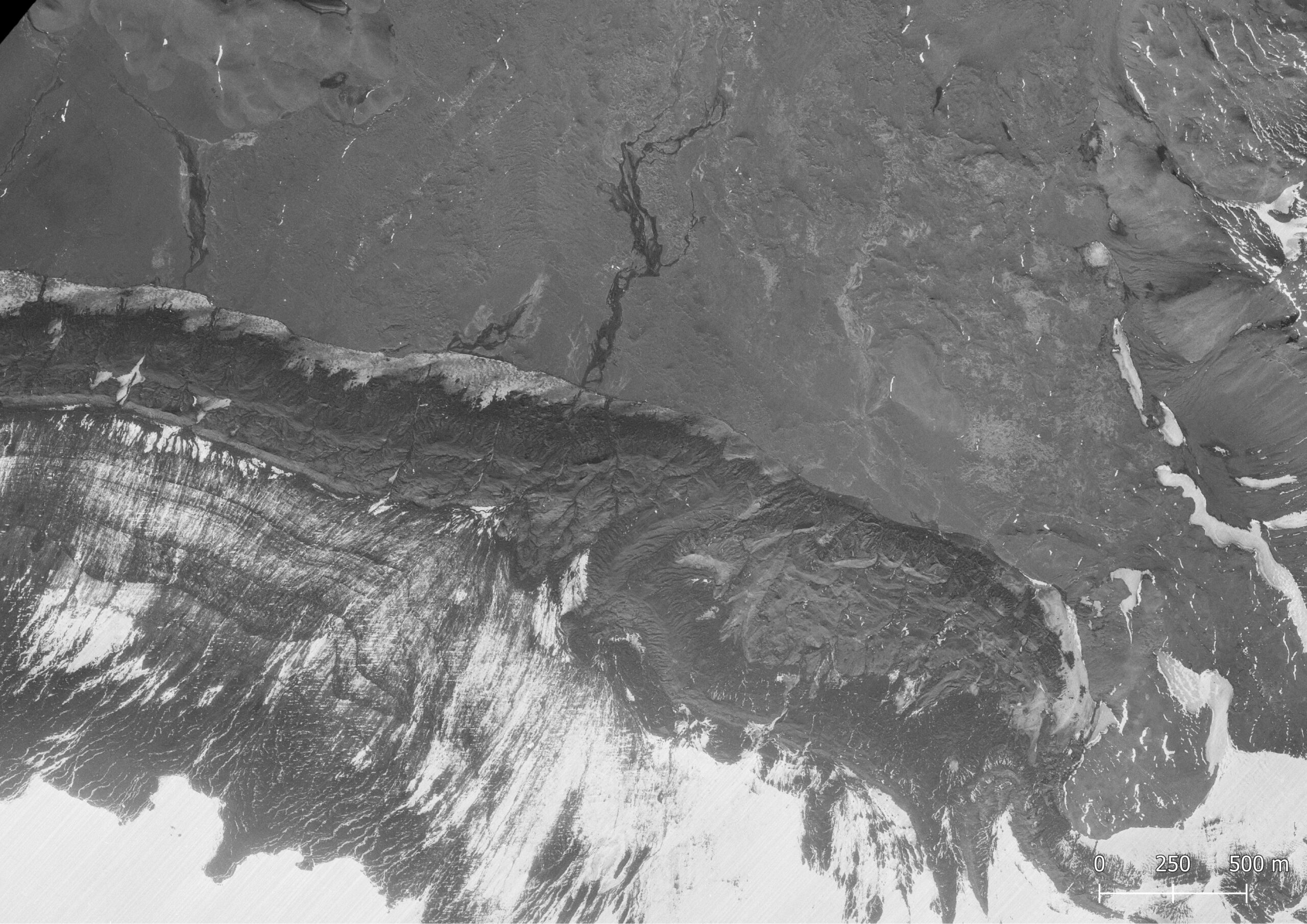

At the other (western) side of Kistufell mountain, the situation is quite different. While Dyngjujökull to its east has receded about one km in the past 20 years, the ice front in the west remained in place. According to the glacier outlines database from the Icelandic Meteorological Office, the part of Dyngjujökull west of Kistufell has been stable since 1890, varying a negligible 200 m (gatt.lmi.is). That’s truly unique for an Icelandic glacier and very remarkable, because the climate has been far from stable over that same period.

Directly west of Kistufell there even seems to be a stretch where the glacier is presently more extensive than ever before. Between 1970 and 1997 the glacier advanced 300 m and a few extra metres since then, without noticeable thinning. The location might explain this anomalous behavior: with an elevation of almost 1100 m, the margin of Vatnajökull is highest around Kistufell. In this very cold and dry climate, the glacier might respond differently (slower) to climate change.

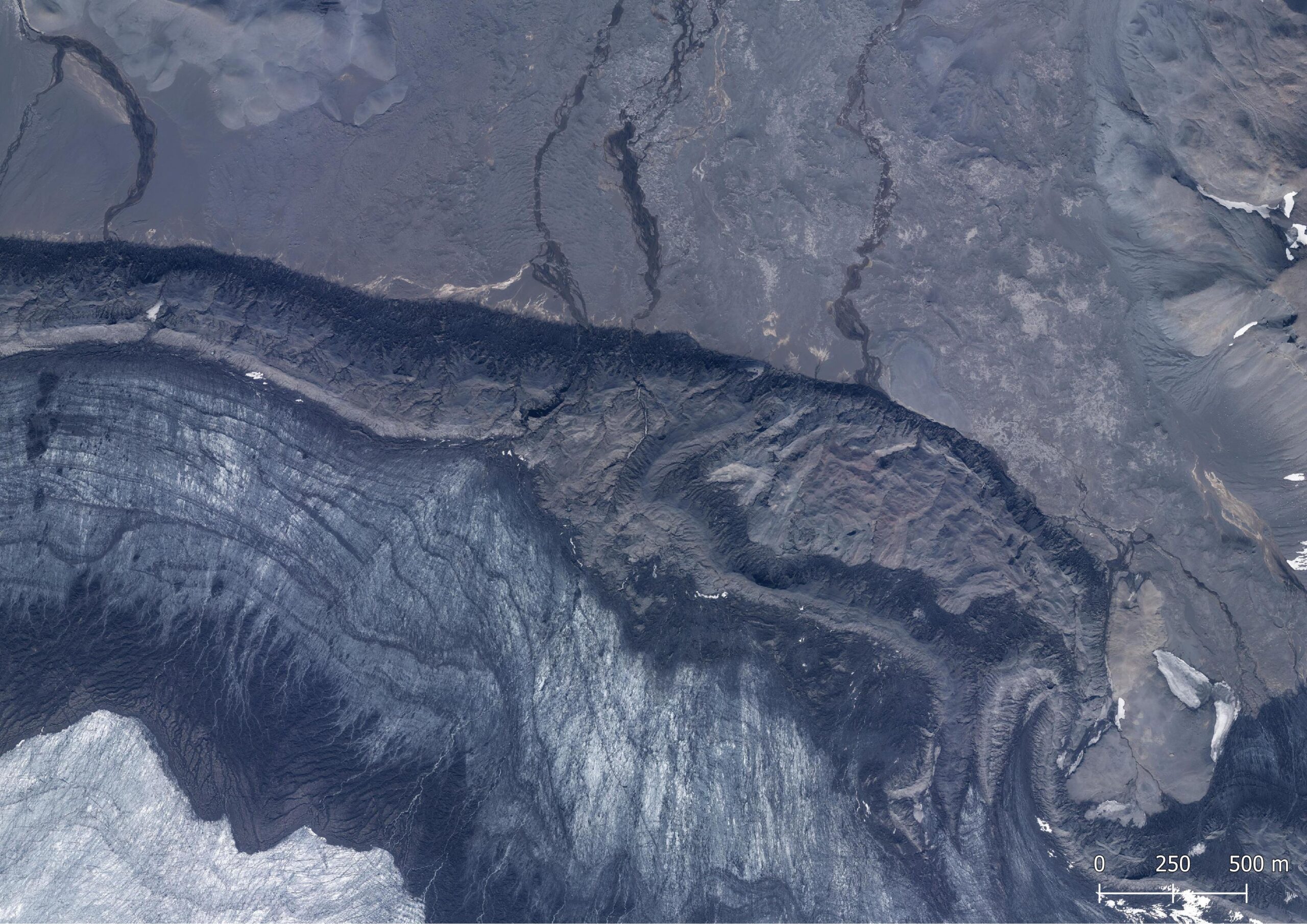

Dyngjujökull west of Kistufell in 1970 (left) and 2021. Source: Landmælinger Íslands and Loftmyndir ehf.

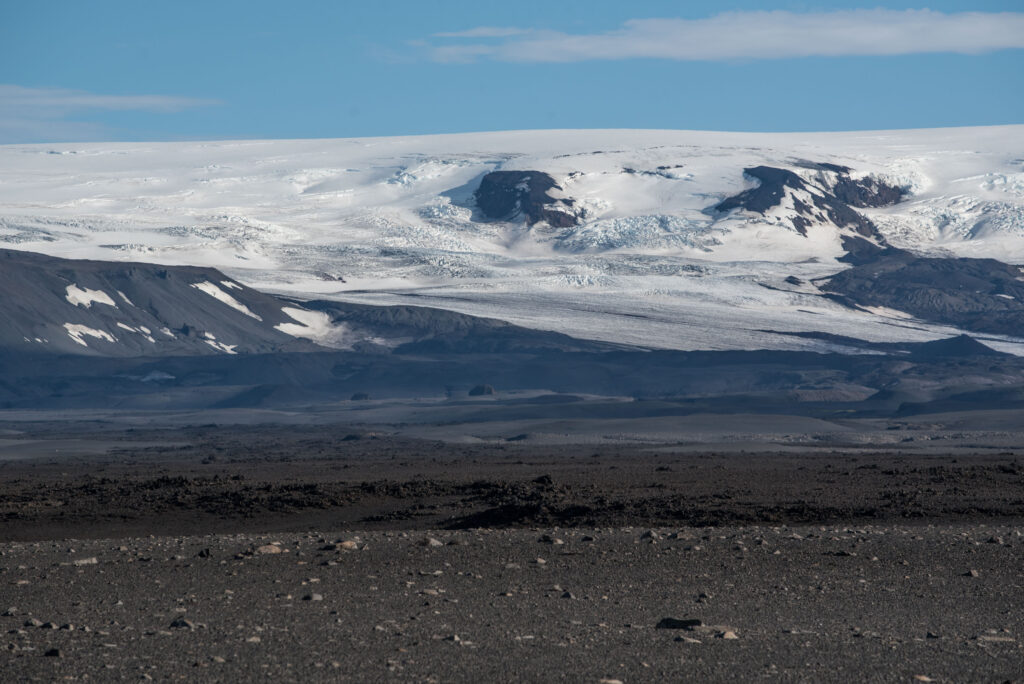

The unique part of Dyngjujökull directly west of Kistufell is hard to reach. A very rough mountain track leads up to Kistufell hut through miles and miles of bumpy lava fields. 2 km of sands and lava fields separate the hut from its name giver. Though flat, the terrain is treacherous, for dry sands can turn into wild rivers within the hour. Most water penetrates the sandy soils here, but abundant meltwater from Dyngjujökull can change conditions quickly.

Once at the foot of Kistufell, only a steep climb of 450 m stands between you and a majestic view over the northwestern part of Vatnajökull. Despite the inhospitable landscape and climate, men travelled this area for centuries on their way across Iceland. They ascended Vatnajökull close to Kistufell to reach the fishing grounds in South-Iceland, for example (Björnsson, 2017: 507).

While Dyngjuökull east of Kistufell receives its ice from the central parts of Vatnajökull, the lobe to the west of Kistufell is more reliant on Bárðarbunga subglacial volcano (and therefore doesn’t surge). This 2000 m high ice dome is one of Iceland’s largest volcanoes, with a caldera 11 km long and 8 km wide. Although it is part of a huge (200 km) and very active volcanic system, no eruptions are known from Bárðarbunga itself in historic times. Nevertheless, the ice dome subsided by dozens of metres in 2014-2015, because magma from the volcanic system erupted 40 km to the north. It formed the enormous lava field Holuhraun. If Bárðarbunga would erupt subglacially it could spark a huge flood.

Chances are global warming will trigger more eruptions, as the thinning ice cap is less capable of suppressing them. At the same time the land rises now the overburden pressure of the ice reduces. Eventually the terrain below Vatnajökull could rebound by 100 m if Vatnajökull melts completely. One of the last glaciers to die is Dyngjujökull, thanks to its elevation and close proximity to the 2000 m high Bárðarbunga.

Search within glacierchange: