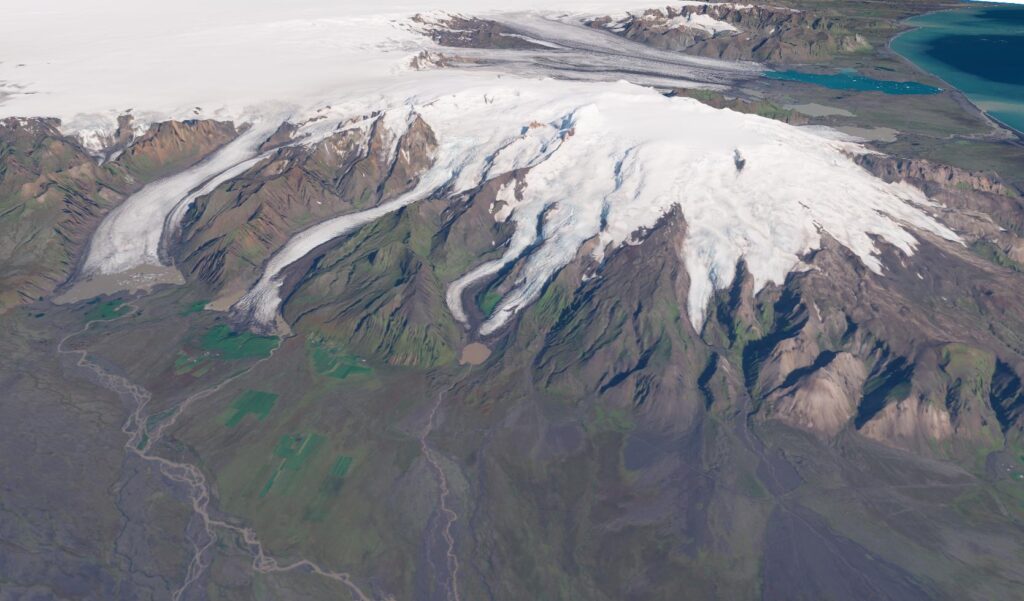

Falljökull is a steep outlet glacier of Oræfajökull. Together with Virkisjökull, it forms a glacier with a violent history and strong fluctuations. At present, the slightly advancing glacier attracts many tourists.

Falljökull descends steeply from the rim of Oræfajökull. At 1200 m the glacier bisects into two arms, the northern arm forming Virkisjökull and the southern Falljökull. They flow on either side of a prominent bedrock ridge named Rauðikambur. Three km down-glacier, at 200 m, the glaciers recombine in their terminal zone. This part could be called either Falljökull or Virkisjökull, as both arms constituted about half the snout (with a medial moraine in between). Nowadays, the name Falljökull makes more sense, as Virkisjökull barely reaches the snout anymore.

In the 19th century the recombined glaciers continued for another 2.5 km. 5000 years before, the glacier was even 2 km longer. Lateral moraines from those days are preserved on Sandfellsheiði, a hill to the south. In front of the glacier only younger moraines are present (apart from a few small isolated remnants close to the main road), because older ones have been washed away by the jökulhlaups of 1362 and 1727. Back then, Öræfajökull erupted and massive floods of meltwater rushed down (Gudmundsson, 1998).

The eruption of 1362 was the most devastating of the two. Pyroclastic waves, ash fall-out and floods destroyed all vegetation. Boulders weighing more than 500 tonnes lie 5 km from Falljökull, transported by a massive flood that is estimated to have had a peak discharge of 100.000 m3 per second, most of it emerging from underneath Falljökull. The area in front Falljökull was renamed as Langafellsjökull, because so many copious blocks of ice were left on the sandur (Roberts and Gudmundsson, 2015). Burning hot pumice, thick ashes and floods killed most livestock and people. Those who survived, abandoned the area. When people returned after some decades, the district previously known as Hérad was given a new name: Oræfi, wasteland in Icelandic (Thorarinsson, 1958).

Falljökull is one of Iceland’s busiest glacier. Everybody who books a glacier hike in this part of Iceland will end up at Falljökull, as it is one of the last glaciers that is easily accessible. Not that long ago, most glacier tours were held at nearby Svínafellsjökull and Skaftafellsjökull, but they have retreated to a point that it’s no longer safe or practical to go there. This means you will often find several groups on Falljökull.

Normal cars have a parking area one kilometer in front of the snout, but excursion companies can park their all-terrain vehicles right next to the glacier. A small dam diverts the meltwater. From here, a zigzag-path is carved out into the steep side of the glacier. One group after the other passes here, everybody with a helmet, pickle and crampons. On the flat snout, they get to walk over the glacier and get a chance to see crevasses from up close.

The glacier tour should start well before the actual glacier. Upon leaving the main road, you pass a flat plain for the first kilometer. Then, the landscape becomes hilly: this is the moraine that was formed in the 19th century, when Fallsjökull-Virkisjökull reached its maximum extent. The normal parking area is just within this moraine. At the end of the 19th century the glacier started to retreat and melt rates increased in the 1930’s.

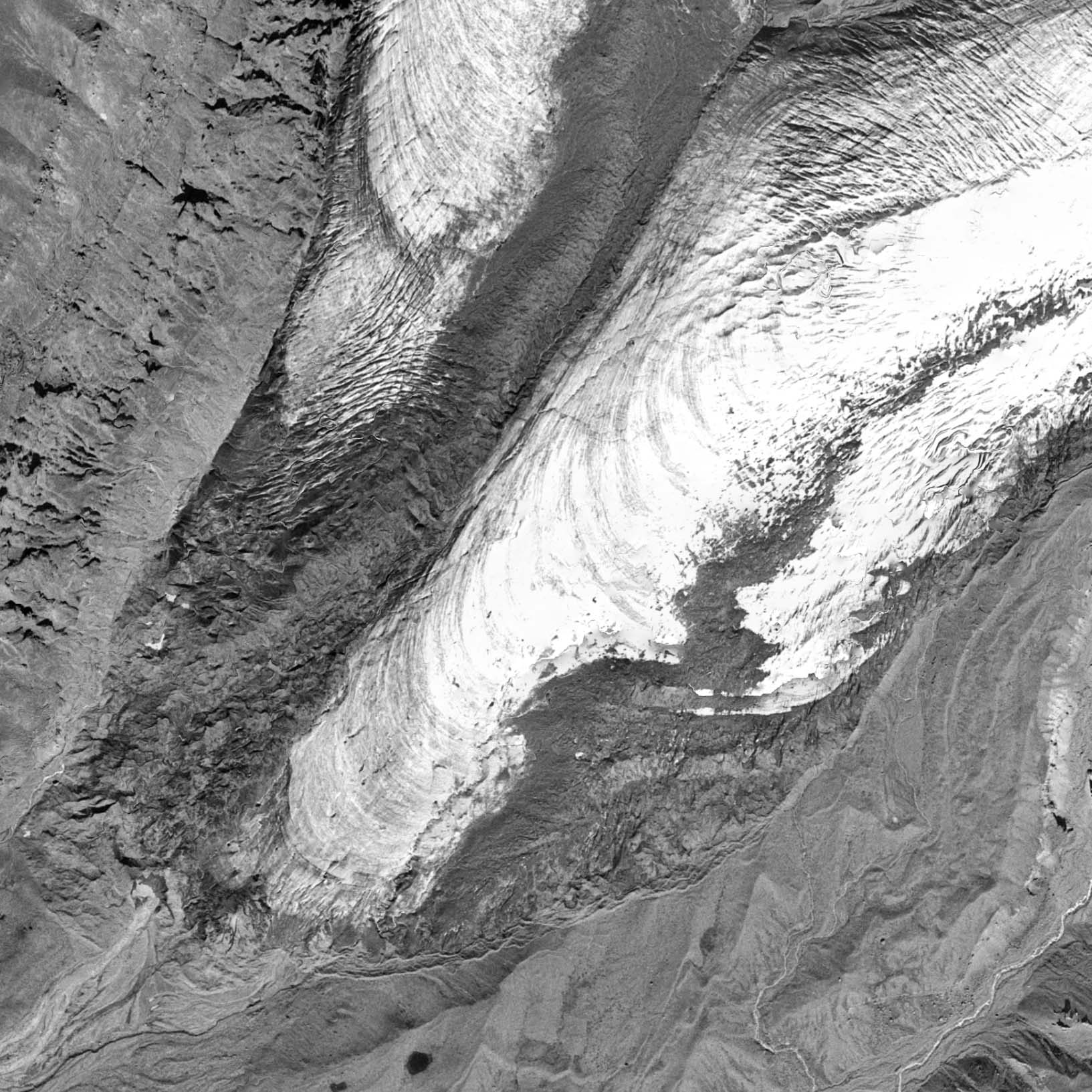

After receding about 1 km, the glacier readvanced slightly between 1975 and 1990. In total, Falljökull grew by 200 m and formed a new terminal moraine some 3 m high. The footpath from the parking area passes this moraine after 600 m. Within the 1990-moraine, annual (recessional) moraines are present. Such moraines form at the margins of glaciers when forward ice-front movement during the winter outpaces the negligible ablation. The resulting small advance bulldozes or squeezes sediment at the ice front to create a minor push moraine. Bradwell et al. (2013) were able to assign a moraine to every year for the period 1990-2003.

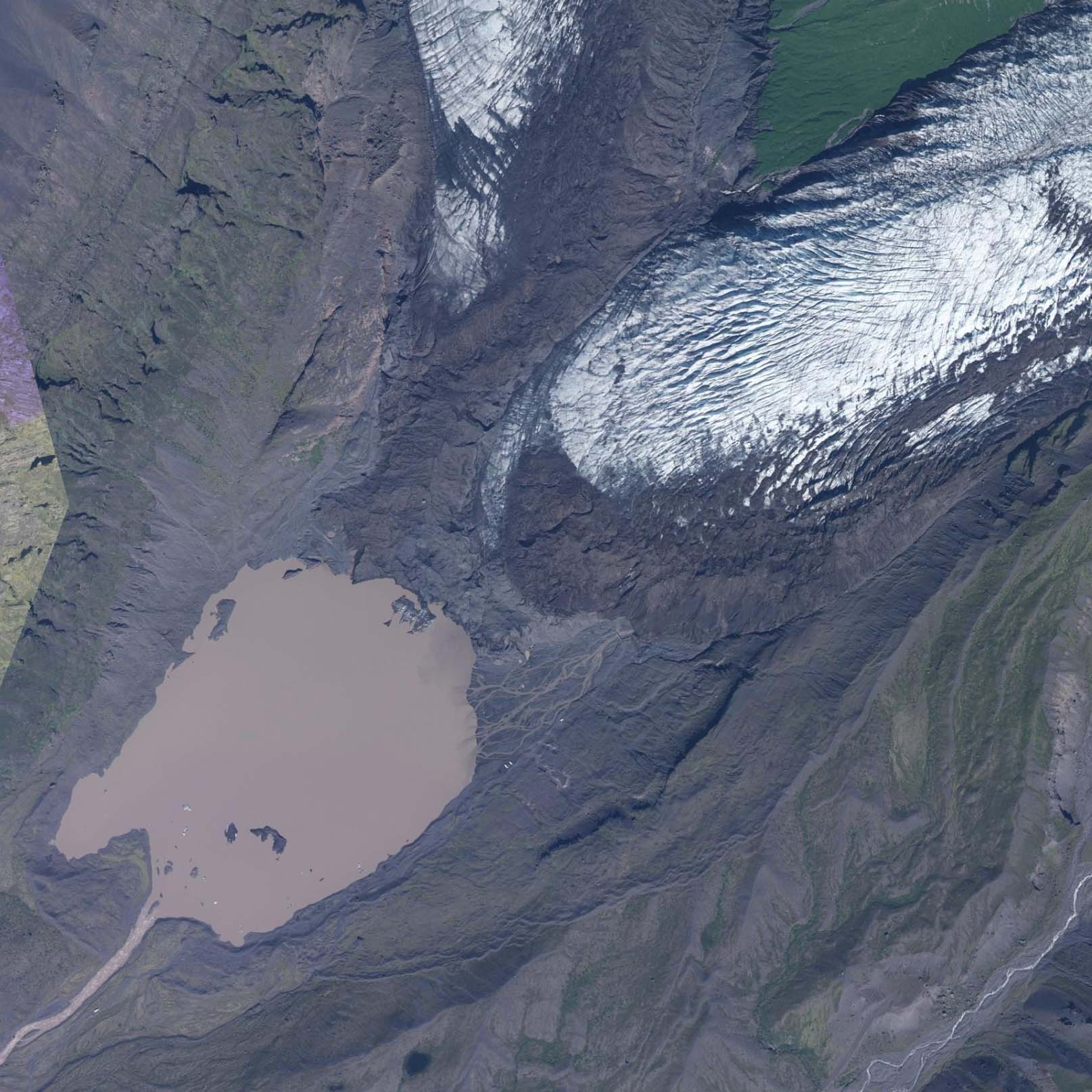

De Falljökull in 1997 (left) and 2021. Source: Landmælingar Íslands.

From 1990 onwards, Falljökull overall receded, with minor advances in winter. For the first five years moraines were formed only a few meters apart, meaning that wintry advance almost equaled summer retreat. In later years, especially after 2000, the ridge spacing increased to 30 m. Summer temperatures were higher, so retreat was stronger, while wintry advance slowed down. After 2004, Falljökull didn’t produce recessional moraines anymore, because the snout became stagnant. It was no longer undergoing forward motion, so it couldn’t form annual push moraines (Bradwell et al., 2013).

A lake appeared from underneath the melting snout. At Iceland’s south coast, most glaciers have eroded their beds to the extent that they sit in depressions that become lakes as the glacier retreats. This also happened at Falljökull, where buried ice melted out and revealed a lake. The first open water appeared around 2007 and the lake has grown to 700 m in length by now. The process of buried ice being replaced by a lake is captured by a timelapse camera of the British Geological Survey.

By 2015, most stagnant ice was melted. Until then, Falljökull receded 40 m and more per year. But since 2015 the length of the glacier has hardly changed. Instead of receding, the glacier is even advancing slightly. A comparison of photos and satellite images shows that the icefall directly above the snout has grown in size. That means more ice is flowing towards the glacier snout. And as summer temperatures haven’t increased further since the start of the 21st century, Falljökull is able to make a very modest forward move.

The growth of Falljökull is mainly manifested in its sides. The northern margin of Falljökull scrapes the old lateral moraine, that is colonized by Alaskan Lupine over the last 20 years. This creates a sharp contrast between the green vegetation and the ice. The southern margin of the glacier has breached the ridge confining it in two places: at a height of 800 m, just east of Grænafjall, where a new debris-covered side lobe is created. And at 400 m, at the foot of the steep slopes of Grænafjall.

When the snout practically stopped moving around 2004, the upper part still flowed down at 50 to 70 m per year. Where both parts of the glacier met, the stagnant ice was overridden by the active ice (Phillips et al., 2014). By 2023, almost all stagnant ice had melted and was replaced by a lake. Only a 50 m wide zone of buried ice remains, purged in between the lake and the advancing ice. Both parts look very different from each other: while the stagnant ice is completely covered by rocks and looks chaotic, the active ice is only partly covered, with a smoother surface and mosses growing on top.

Falljökull is one of few glaciers that has mosses growing on its surface. For moss to colonize the ice it needs clasts lying on the glacier surface. The mosses insulate the ice and become elevated on a pedestal. It eventually falls off and moves across the glacier surface, whereby it achieves a rounded form. Because of their roundness and ‘movement’ these moss cushions are called glacial mice (Porter et al., 2008).

While Falljökull is growing a little bit in size, Virkisjökull keeps receding, albeit slowly. A possible explanation for their different behavious is Virkisjökull’s hypsometry. The lower 2 km of its snout is below 400 m, while only 1 km of Falljökull is below 400 m. An increase in snowfall in the accumulation zone has therefore less effect on Virkisjökull, a glacier that would benefit more from cooler summers. But whatever the reason, the effect is that Virkisjökull transports less ice to the combined snout and could detach from Falljökull within the next ten or twenty years.

Search within glacierchange: