Glacier du Mont Miné (Mont Miné Glacier) and Glacier de Ferpècle (Ferpècle Glacier) are two glaciers in Ferpècle valley, south Switzerland. Fossil trees and old travelogues help to reconstruct their history.

The Mont Miné Glacier and Ferpècle Glacier (to its east) start at Tête Blanche, a 3710 m high mountain that borders Italy. From there, both glaciers flow in a northerly direction for 5 km. On their way down they get divided by the ridge of Mont Miné.

For a long time the glaciers rejoined in front of Mont Miné. But throughout most of the 20th century the glaciers retreated. Eventually, Ferpècle Glacier disconnected from Mont Miné Glacier in 1957 and has its own snout since then. Just before, a glacier-dammed lake was temporarily formed at their confluence. Its most dramatic drainage event was in 1953, when several bridged down-river got destroyed (Bezinge, 2001).

Because the glaciers share their accumulation area, they behave similarly: continuous retreat over the last 150 years, interrupted by a small advance in the 1980’s. However, their snouts look quite different. Mont Miné Glacier is dissected by an ice avalanche at 2600 m, after which its flat and debris-covered snout continues for another 1.5 km. Before circa 2006, the upper and lower parts were connected by an icefall instead of an ice avalanche.

Snout of Ferpècle Glacier in 2006 (left, jcplus via Flickr) and 2022.

Ferpècle Glacier, on the other hand, flows down more gradually. Its snout is thinner and broke in two in 2019. The lower part melted within a few years, and did so via a picturesque meltwater cave. The glacier is the better accessible of the two, as a trail runs along its western margin. It connects the abandoned Bricola hut to Cabane de Dent Blanche (3506 m) and further to Col de Tête Blanche connecting Ferpècle with Zermatt.

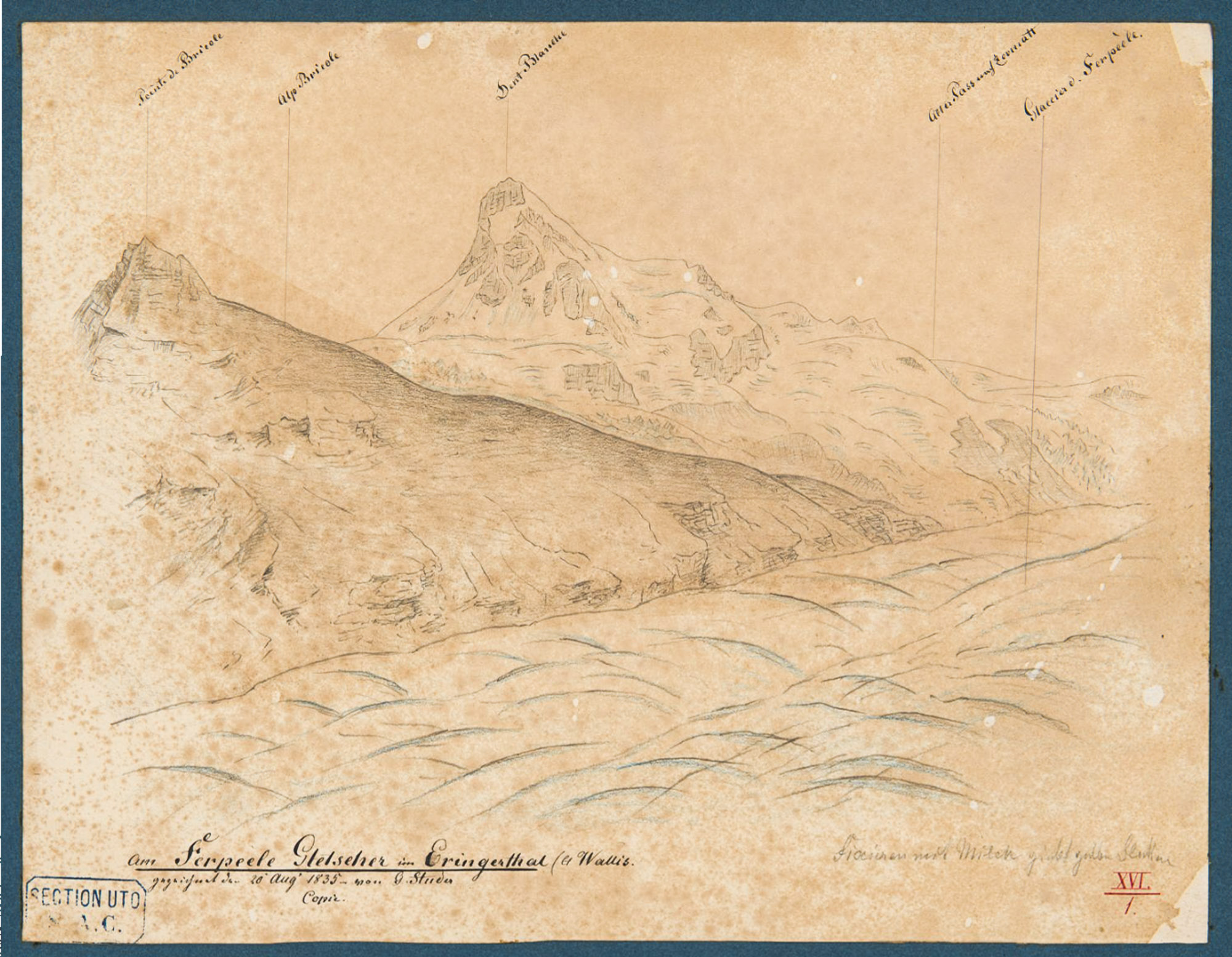

How different was the scenery in the mid-1800’s, when the glacier extended 2 km from the foot of Mont Miné. The glacier’s maximum extent more or less coincided with the first foreign travelers visiting the area. The German Julius Fröbel went to Ferpècle Glacier in 1839 and the Scotsman James David Forbes in 1842. Both were very negative about the local people’s disposition, but all the more lyrical of the landscape.

On a late July-evening in 1842 James Forbes stood at Bricola, a chalet above the glacier. He wrote: ‘’As now seen by moonlight, its appearance was indescribably grand and peaceful, and I stood long in fixed admiration of the scene, the most striking of its kind which I have witnessed (Forbes, 1843:294).’’

Julius Fröbel explored some valleys in Valais in the summer of 1839. Besides notes about local customs, topographical names and geology, he also had a look at some of the glaciers. At Ferpècle Glacier, or Biegno däu Ferpekhlo in local dialect according to him, he noticed how the braided river in front of it must have swallowed up pastures, as relics lay as islands in the river. Then, he came up to the glacier itself. It had reached a moss-covered rock outcrop with some trees on top of it, which was surrounded by a ‘’waterfall-like glacier’’ on one side and a hanging glacier on the other (Fröbel, 1840:110).

Fröbel was guided by a local notary who told him about a glacier flood in 1828 that took a huge Swiss pine. In his days, only larch trees could grow in the valley, which are better adapted to the cold. Moreover, he had knowledge of a document in the archives of Evolène from the 15th century concerning fertile fields at Les Manzettes, overrun by the glacier in later times. Just like the meadows, the document was lost, probably in a fire in 1934 (Röthlisberger, 1973:20). Last but not least he said that ‘’everybody in the village’’ knows of Roman coins, horseshoes and halberd points from the Middle Ages that have been found on the glacier (Fröbel, 1840:112).

All these remarks indicate that the glacier must have been much smaller in the past, if present at all. Hay was harvested where the glacier was in 1839, trees grew higher up, and the valley was crossed by horses and people, unthinkable in the glaciated valley of the 19th century. Luckily, there is science to test these anecdotes.

While advancing, the glaciers of Mont Miné and Ferpècle constructed huge lateral moraines. In it, old soils and logs are preserved. As the glaciers recedes, their moraines become instable and erode, exposing the embedded tree trunks again. 35 of them were dated by dendrochronology, a technique in which the trees are dated with the help of their growth ring sequences. Most of them turned out to have died between the years 1285 and 1311, so the glacier must have been advancing then. Somewhere in the 14th century the glacier reached a maximum extent that was similar to the size in the 19th century (Nicolussi et al., 2022).

This early peak in glacier extent was possibly initiated by a cluster of large tropical volcanic eruptions and ended around 1380. It was followed by a warmer period that lasted well into the 16th century (Nicolussi et al., 2022). This is in good agreement with the meadows deep in Ferpécle valley, but also reveals that their location had been glaciated before. So maybe the farmers of the 16th century told each other stories about a once-glaciated valley, not knowing it was about to happen again.

Ferpècle (far left) and Mont Miné glaciers in 1902 and 2022. Source 1902: Harry Fielding Reid, Library ETH Zürich photo Hs_1458-GK-B025-1902-0001.

![Dirt bands [Schmutzbänder] on Ferpècle glacier, 1902 [?] Ferpècle (far left) and Mont Miné glaciers in 1902. Source: Library ETH Zürich.](https://glacierchange.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/19700213-hs_1458-gk-b025-1902-0001-scaled.jpg)

To make things even more complicated: most of the trees that were killed by the glacier in circa 1300 were growing on an older moraine. That means there was another period of large glaciers before the trees germinated, probably in the 6th century (Nicolussi et al., 2022). Now, the foreland of the glaciers is once again being recolonized by trees (Ngan Tu et al., 2024).

At some point during the many stages of glacier extent in Ferpècle valley, horseshoes, coins and halberd points were lost. At least, if the villagers of Evolène are right. Possibly, the items (and owners) were lost while crossing Ferpècle Glacier into Mattertal, like Forbes did in 1842. He did so when the glacier was exceptionally large. Does that make the traverse easier, as the glacier smoothens the precipitous cliffs, or harder due to crevasses?

We’ll soon find out what the crossing is like without glaciers.

Search within glacierchange: