Fjallsjökull is the largest glacier that descends Öræfajökull volcano. After a series of icefalls, Falljökull terminates in lake Fjallsárlón, where icebergs break off from the impressive calving front.

Fjallsjökull is a popular glacier, thanks to the lake full of icebergs in front of its large calving front. Many people book boat tours here to sail in between the icebergs and along the calving edge, which is up to 35 m high (Bell, 2018). One can even sleep in ‘igloo boats’ that drift in the lake. But a hundred years ago, there was no lake, let alone boat tours.

At the end of the 19th century, Fjallsjökull was bigger than it had been for thousands of years. The glacier splayed out to form a piedmont lobe and was coalescent with Breiðamerkurjökull to the east. it receded slowly between 1900 and 1930. Then, a 20-year long period of increased melt started, revealing the easternmost part of the overdeepening that developed into Fjallsárlón lake. In 1946 the glacier became separated from Breiðamerkurjökull, whose western meltwater river Breiðá flows into Fjallsárlón since 1954 (Björnsson, 2017:462).

To the west, Fjallsjökull originally coalesced with another glacier, called Hrútárjökull. They were therefore together called Hrútárjökull and began separating from 1945 onwards. However, it took until the start of the 21th century for them to lose all contact. The ridge that now lies in between the two glaciers is composed of material of the former medial moraine. At one place the ridge is incised by a spillway that formed in 2002-2003 and catastrophically drained a lake (Evans et al., 2023).

While receding, Fjallsjökull left behind recessional moraines. Most of them are constructed in winter, when the glacier creeps forward a bit and forms a ridge by squeezing and pushing subglacial till. Along the shores of Fjallsárlón, extensive areas of closely spaced recessional moraines were formed in the 1930’s and 1940’s.

More recently, Fjallsjökull has left behind recessional moraines on its southern margin. These moraines, generally 1 m high, are extremely sawtooth in form, which mirrors the crevassed morphology of the ice margin. Some moraines look like hairpins, as they have very long limbs that indicate places where sediments have been squeezed into longitudinal crevasses.

Remarkably, the moraines to the south Fjalljökull are formed more frequently than once a year. In between the higher, wintry recessional push moraines lie several smaller (0.4 m high) squeeze moraines that have been formed during the melt season. The abundance of meltwater makes the ground beneath the glacier water-soaked and the material is then squeezed into marginal crevasses and to the margin by the overburden pressure of the ice. The stronger the melting and recession are, the more squeeze moraines are formed. The ridges that are constructed this way in early summer will be preserved, while late-summer ones could be obliterated by the next wintry advance. But even if they are not overwritten, their preservation potential is low due to their small heights (Chandler et al., 2020).

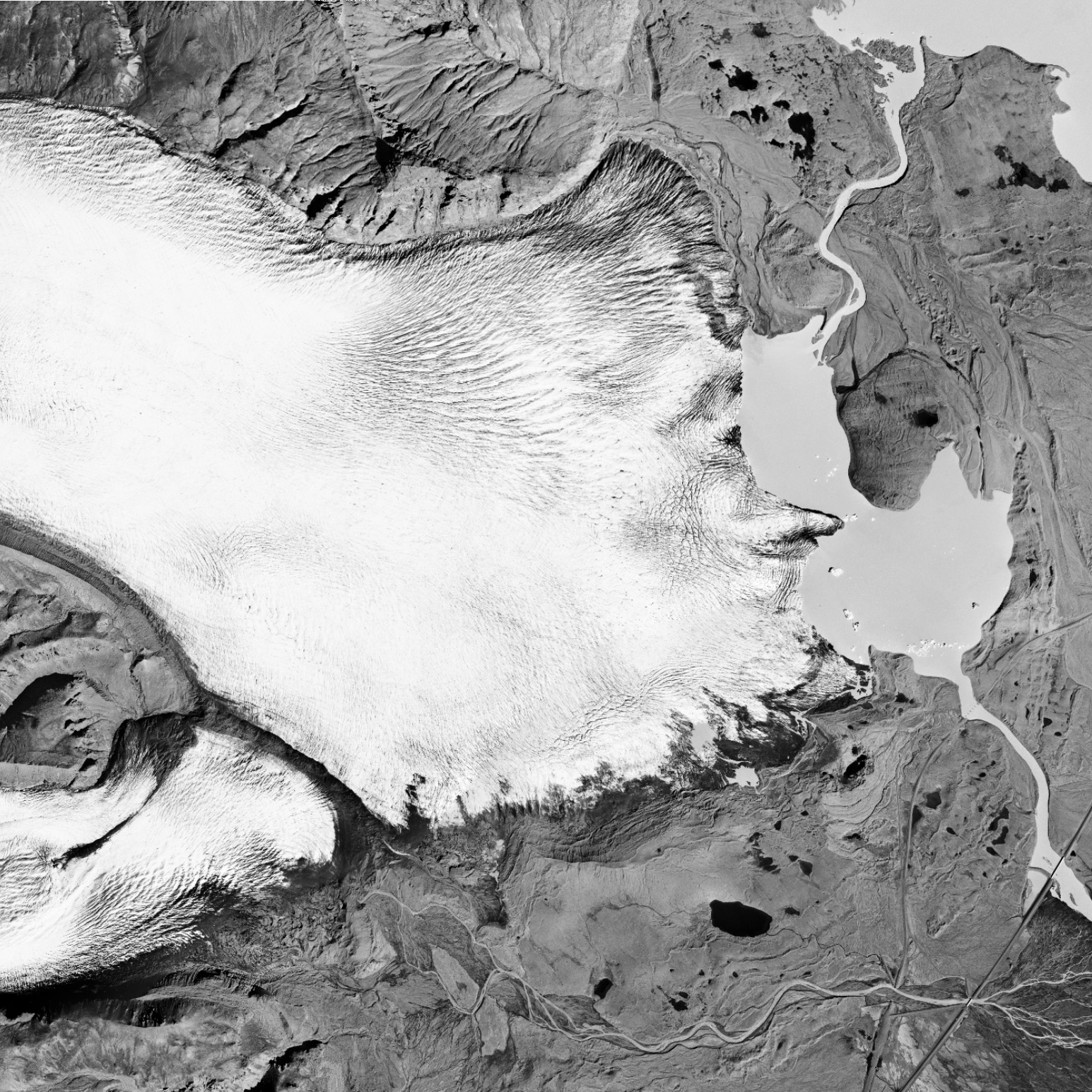

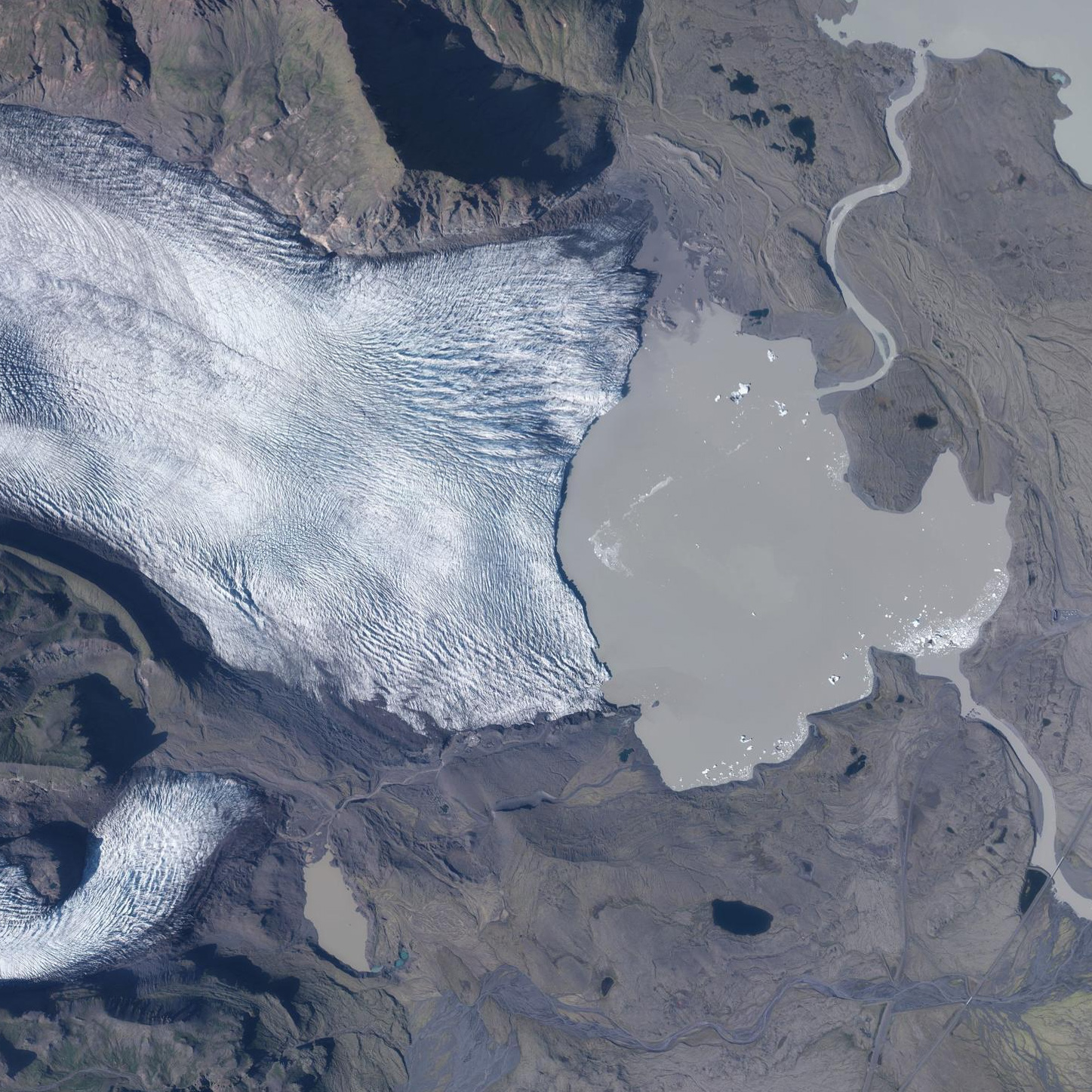

Orthofhoto of Fjallsjökull in 1998 (left) and 2021. Source: Landmælingar Íslands and Loftmyndir ehf.

Moraines are formed where Fjallsjökull terminates on land, but most of the snout now ends in the proglacial lake Fjallsárlón. Due to higher summer temperatures, the glacier thinned and strongly receded since the late 1990’s, consequently expanding the lake. And as the calving front of Fjallsjökull moved westward, it receded into deeper waters. That has induced a problematic positive feedback loop.

Now that the glacier is situated above the deepest part of the lake, the snout has become nearer to flotation. The increased buoyant forces have reduced basal drag (resistance from the lake bottom). Therefore, the glacier snout experienced a strong increase in flow velocity. In comparison to 1990, the glacier doubled its speed to up to 200 m per year. The higher flow velocity stretches the ice in return, thinning the ice (longitudinal extension), increasing crevassing and therefore calving (Dell et al., 2019).

The speed of the glacier is dictated by the bed topography: where the lake is deepest, the flow velocity is highest. The trough that holds lake Fjallsárlón continues for another 3 km up-glacier and will therefore expand as the glacier retreats. Its bottom is deepest in the north, where a trench is carved out 200 m below sea level. In the south, there is a second channel, 120 m deep. Where the glacier overlies these deeper parts, (relative) buoyancy of the glacier draws most ice down and Fjallsjökull’s speed and calving rates are highest (Dell et al., 2019).

Change of the calving front over one week time: July 8th (left) and 15th 2021. Data: Baurley (2022) via zenodo.org.

Now that the glacier’s margin is situated above the deepest part of the lake, a positive feedback mechanism between longitudinal extension, calving activity, frontal retreat and increased velocities occurs, termed dynamic thinning. The calving front has accelerated to a maximum of 1.2 m a day and calving events have become more frequent. Calving mainly happens above thermal erosion notches, which are incision at the waterline that undercut the ice. Here, the lake water melts up to 1 m of ice every day. This way, the ice above the notch becomes instable and eventually collapses (Baurley, 2022).

It could be argued that an increase is flow velocity should lead the glacier to advance. After all, more ice is transported to the snout. But as calving has increased just as much as (and even outpaces) the increase of ice transport, the result is an ever shrinking glacier. There is one place though where the snout of Fjallsjökull terminates more or less on land. Despite rising temperatures, this northern section has barely retreated since 2009, coincident with the increase in flow velocity.

Eventually, Fjallsjökull will retreat out of its overdeepening. That will reduce its flow velocity, but would inevitably also put an end to calving. Although it will take several decades for the glacier to leave the lake, the company that offers boat tours on Fjallsárlón is already monetizing climate change by suggesting it might be your last chance to visit the glacial lagoon. Or just another chance to profit from climate change?

Search within glacierchange: