Fláajökull is a southeastern outlet glacier of Vatnajökull, with exceptional moraines and a turbulent history.

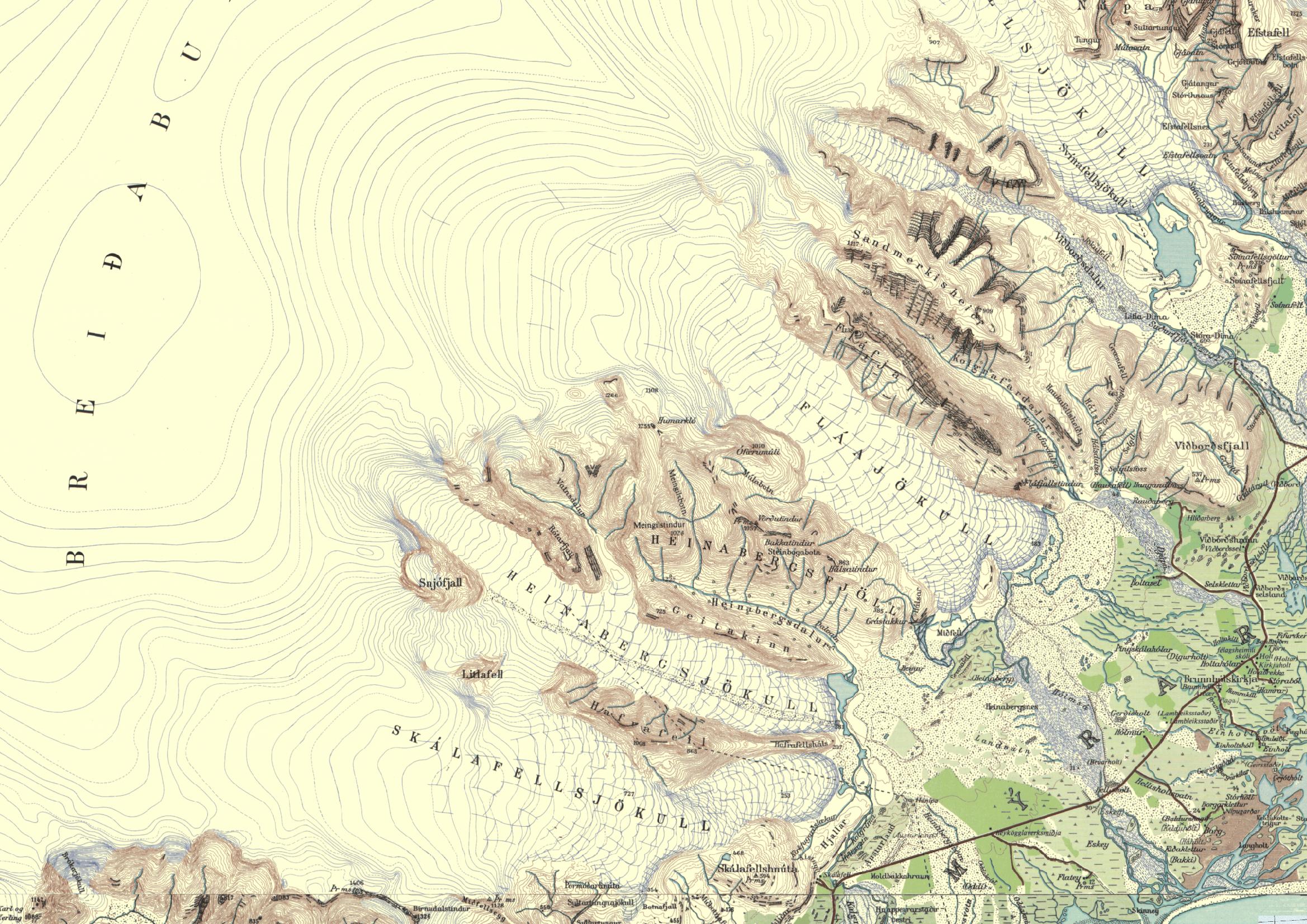

The most elevated part of eastern Vatnajökull is formed by Breiðabunga. Because of its height (1500 m) and close proximity to the sea this dome of ice receives lots of snow, enough to sustain multiple glaciers of twenty kilometers long. One of them is Fláajökull.

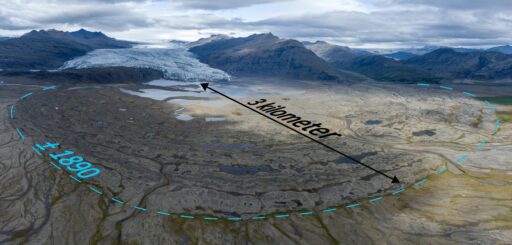

Up until the fifteenth century, outlet glaciers emanating from Breiðabunga were very modest due to a warmer climate. From then, the climate cooled and the glaciers started to cover fertile lands. Meadows were engulfed by the expanding glaciers and farms deserted. After expanding for a few centuries, the glaciers reached their maximum extent in the nineteenth century. While advancing, the glacier periodically experienced stagnation, forming moraines that were later overridden by the glacier again. Such arches of intermediate moraines are still recognizable, especially from above. The outer ring is deposited over the years 1880-1890 and forms the glaciers maximum extent.

Around 1900 Fláajökull started to recede, causing new problems for local farmers. Meltwater found an alternative route, running eastwards into Hleypilækur instead of southward through Hólmsá river. This new course threatened other farms, as Hleypilækur suddenly became a much bigger river. Dozens of man and horses were put to work in 1937 to dig a channel through the moraines in order to guide Fláajökull’s meltwater back into Hólmsá river. At the same time river Hleypilækur was dammed, but as the flow was narrowed the current became even stronger, flushing away all new loads of landfill. Finally, the wagons themselves were filled with rocks and dumped into the river, making it a calm brook again. The battle was won, for the moment (Björnsson, 2017: 477).

Fláajökull around 1900 (left) and in 2023 from the shore of Holmsá river near Stóra-Sandsker. Source 1900: Royal Danish Geographical Society, ES-212236.

In the middle of the twentieth century the ever receding glacier made room for a new meltwater river to flow eastwards. Again, people erected dams to prevent this from happening and guide water into Holmsá river, but that river can cause damage as well. Like in September 2017, when weather was extremely wet in this part of Iceland. Water levels in Holmsá river were so high that Icelandic authorities made three big gaps in the main road to let water trough. Otherwise, the entire road and several farms along it could have been flooded. While these gaps were fixed a few days later, the footbridge upstream was damaged beyond repair on September 27th.

Just one month before, a new hiking route from Skálafell to Haukafell was officially opened. Three new foot bridges spanning wild rivers should tempt more tourists to spend time in this area. But four weeks after the last bridge was finished, heavy rains made it impossible to complete the new hike, as the only three years old bridge over Holmsá river was washed away. A smaller bridge in a nearby stream was also destroyed. Besides making the trail useless, the Jökulfell in front of Fláajökull became inaccessible again. In 2023 construction started for a new bridge, finally.

Both the former and the new bridge span Holmsá close to Jökulfell, a mountain of two hundred meters high that splits the snout of Fláajökull. For a long time the mountain was completely covered by the glacier, but around 1930 glacial thinning revealed the top. During the twentieth century the glacier kept on thinning and receding, although not always at the same rate. After 1965 the retreat was halted and even reversed for some years at the end of the 1980’s. The glacier margin was stagnant for five years, giving the ice time to push up a new end moraine of some ten meters high.

At the turn of the century melt rates strongly increased. How much Fláajökull has receded since then is manifested in its recessional moraines. These are low moraines of about one meter high formed in wintertime, when the ever forward moving glacier can advance a little bit because of cold weather (thus no melt to counterbalance the forward motion). When summer kicks in, the glacier recedes again, followed by a wintry advance. But because the glacier recedes by more meters in summer than it grows in winter, a sequence of parallel moraines is formed. They read as growth rings, with the younger ones closest to the glacier.

Nowadays the glacier doesn’t leave behind new recessional moraines anymore. Fláajökull has receded so much (about three kilometers in total) that it now ends in a lake, making it also harder to measure annual length change. The lake was formed by Fláajökull itself, as it has been excavating its bed for hundreds of years. Most erosion is happening where the glaciers velocity is greatest, in this case the relatively narrow valley at the upper part of the snout close to Fláfjall mountain. There, even four kilometers of the glacier base is below sea level! When the glacier melts even further in the coming decades a very big lake will appear, just as Jökulfell did a hundred years ago.

Search within glacierchange: