Skeiðarárjökull is a glacier full of danger, with its subglacial volcano’s. Another landscape feature that can bring havoc upon the glacial foreland are ice-dammed lakes, like the once enormous Grænalón lake.

The written history of Grænalón starts as early as the year 1201. That year there was such a catastrophic flood from the lake that people felt the need to write it down on the little paper they had. Luckily these papers have been preserved, as they hold valuable information about the extent of Skeiðarárjökull in those days. The glacier must have reached up to lake Grænalón, as it was able to dam it. In subsequent centuries there are no reports of Grænalón drainage events. Although this might indicate a retreated glacier, it is more likely to be a consequence of abandonment of the Skeiðarár plain. Farming there became too risky, so there was nobody living there anymore to be affected by the floods, let alone to write about it (Thórhallsdóttir en Svavarsdóttir, 2022).

The second account of a flood emanating from lake Grænalón dates from 1785, almost six hundred years after the first one. Skeiðarárjökull must have grown considerably in the meantime. And the bigger the glacier, the higher the dam that blocks Grænalón. The water level in the lake could therefore rise, though not unlimited: at 640 meters above sea level a col on the southern side of Grænalón governed the maximum elevation of the lake (Roberts et al., 2005). Beyond this point the water would flow over the col and eventually into Núpsa river.

Between 1785 and 1939 Grænalón was larger than ever. The lake measured about six kilometers in length, was up to three kilometers wide and at places over a hundred meters deep. Grænalón stretched so far to the west, that another glacier terminated in it at the other end. This glacier was aptly named Grænalónsjökull. In total, the lake could hold two cubic kilometers of water. For an event in 1898 it is known that all this water drained in just four days. The floodwater attained a maximum discharge of five thousand cubic meters per second and caused one fatality and significant degradation of farmland (Roberts et al., 2005).

Throughout the first 40 years of the twentieth century, jökulhlaups from Grænalón were comparable to the one in 1898. Each time the water pressure was high enough, the lake drained subglacially via an inlet at the lowest part of the lake bed enabling full drawdown. The water found its way under the glacier and propagated seventeen kilometers. It reappeared at the snout, bursting out from underneath the ice and inundating the western regions of Skeiðarársandur, routing primarily through the Súla river. Between 1935 and 1949 this happened every three to four years (Harrison et al., 2023). Afterwards the lake bottom would be filled with stranded icebergs.

After 1949 the lake would never again reach the maximum level. Instead of coursing beneath the ice dam, flood water cascaded over an ice buttress in the southeast corner of Grænalón. Behind the buttress there was (and still is) a trench at the flank of Skeiöarárjökull where water collected. The trench used to be about three kilometers long and the water entered a subglacial inlet at the end of it. This change of drainage regime substantially lowered the maximum water level, from 640 meter to about 580 meters. Jökulhlaups therefore were smaller, but they did became more frequent. From 1951 to 2011 the lake erupted 39 times with an maximum total discharge of 0,3 km³, seven times smaller than before. In 2001 Grænalón lowered even further to 520m and jökulhlaups were the product of just a few meters drawdown of water level.

Grænalón periodically released flood waves onto the plain down-glacier, so a long bridge over the river Súla/Núpsá was necessary. But with the disappearance of Grænalón, together with the changing course of Súla river (eastward, merging with Gígjukvísl) there was no longer need for the 420m long single-lane bridge. In 2023 the bridge was replaces by a much shorter two-lane one.

Skeiðarárjökull is thinning every year. Where it used to dam Grænalón, the glacier is losing five meters every year on average (Magnússon et al., 2020). In the heydays of Grænalón the lake used to be dammed by an ice wall 150 to 200 meters in height, but nowadays there only remains a fragment of maybe ten or twenty meters. Still an impressive sight, but by no means enough to hold back any water. Without a dam or ice buttress the jökuhlaups went extinct, the last event occurring in 2011. The remaining ‘puddle’ of water slowly fills up with sediments.

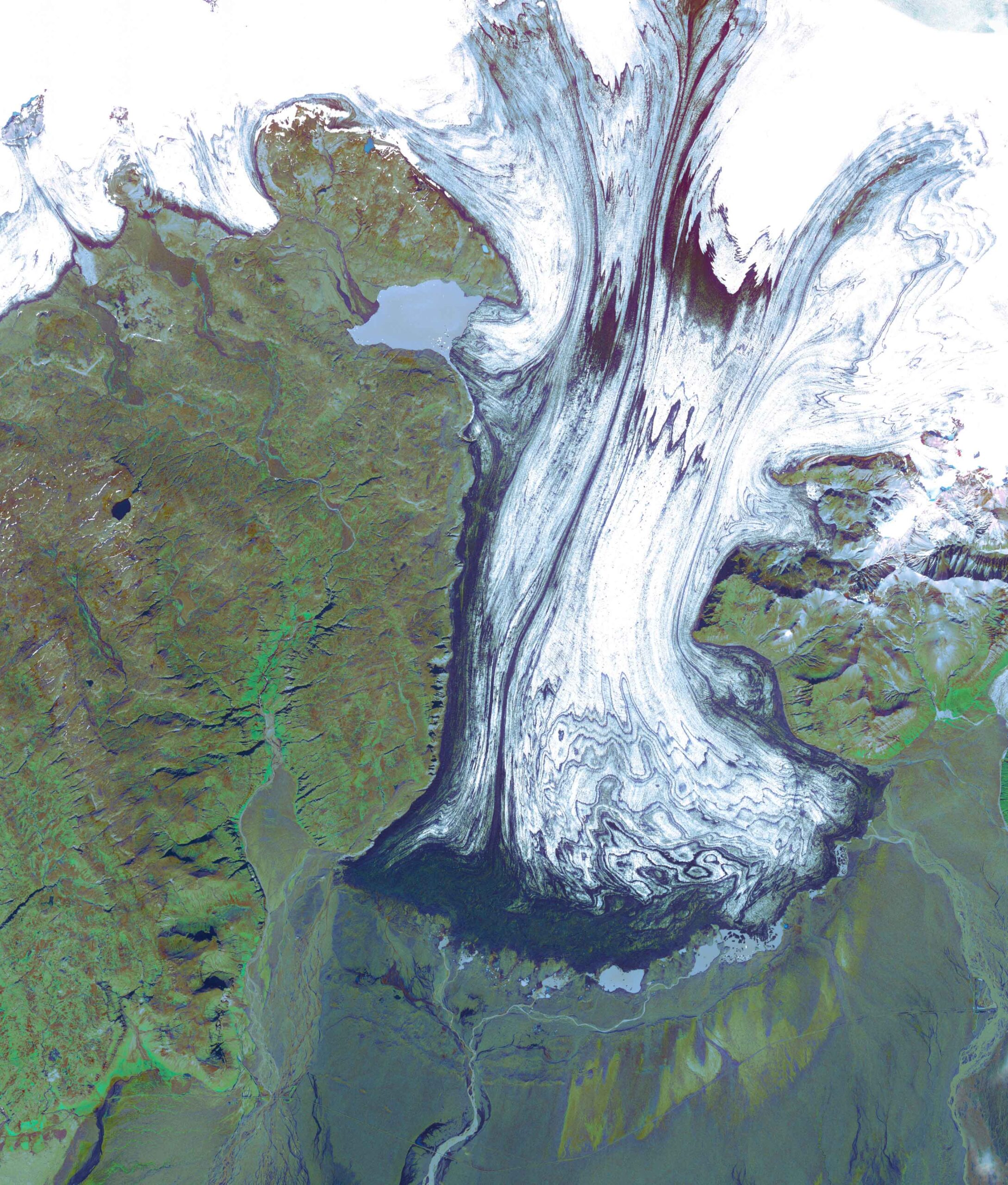

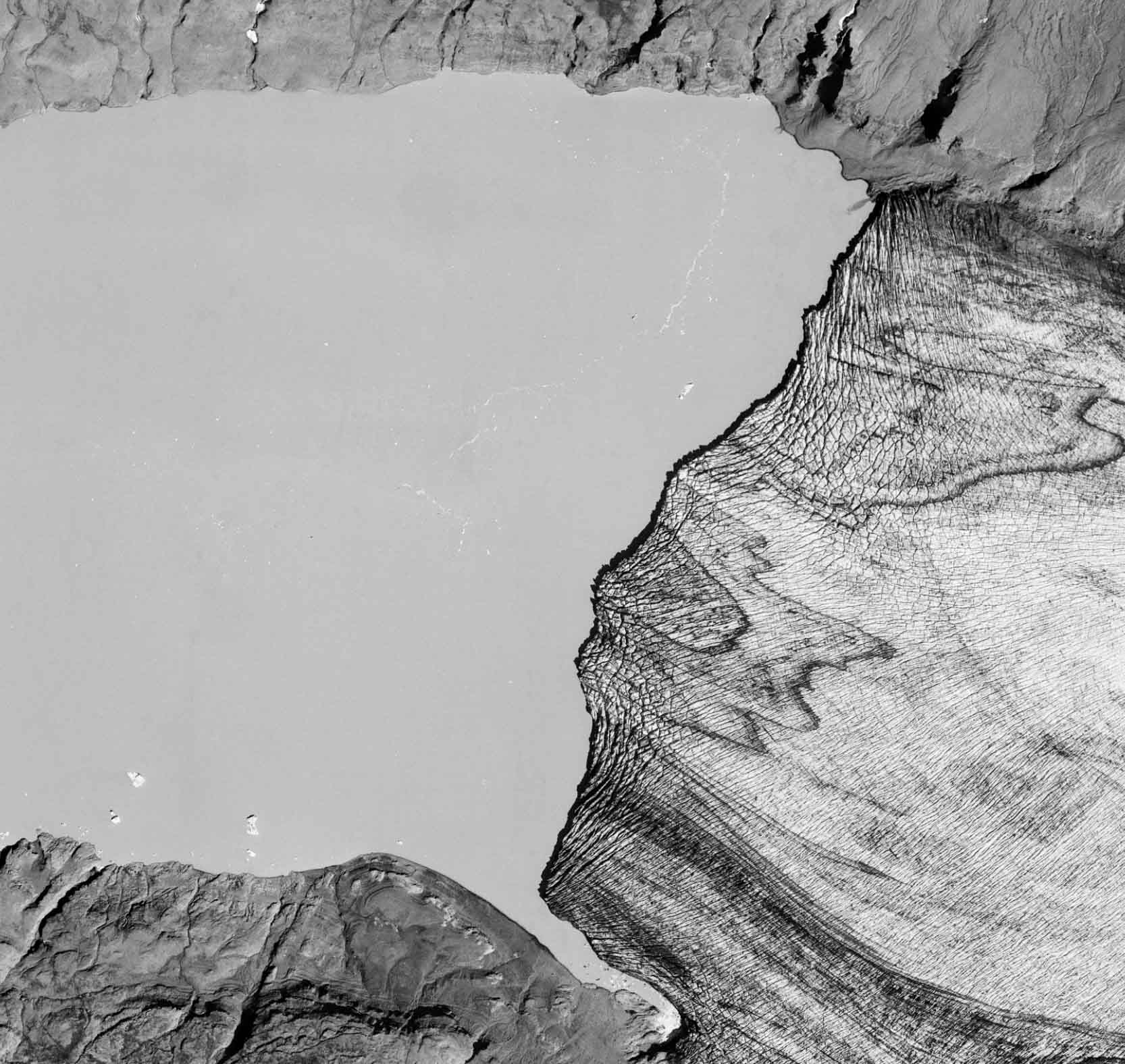

Grænalón in 1997 (left) en 2017. Source: loftmyndasja.lmi.is.

At the interface of the glacier and the mountains slopes there remains a trench. While it used to only carry water when the lake emptied, the trench now serves as a normal river. Well, maybe not that normal: a drainage channel carved deeply into the glacier with twenty meter high vertical walls of ice is by no means your everyday river. Blocks of ice regularly break off, falling into the river below or even onto the opposing shore.

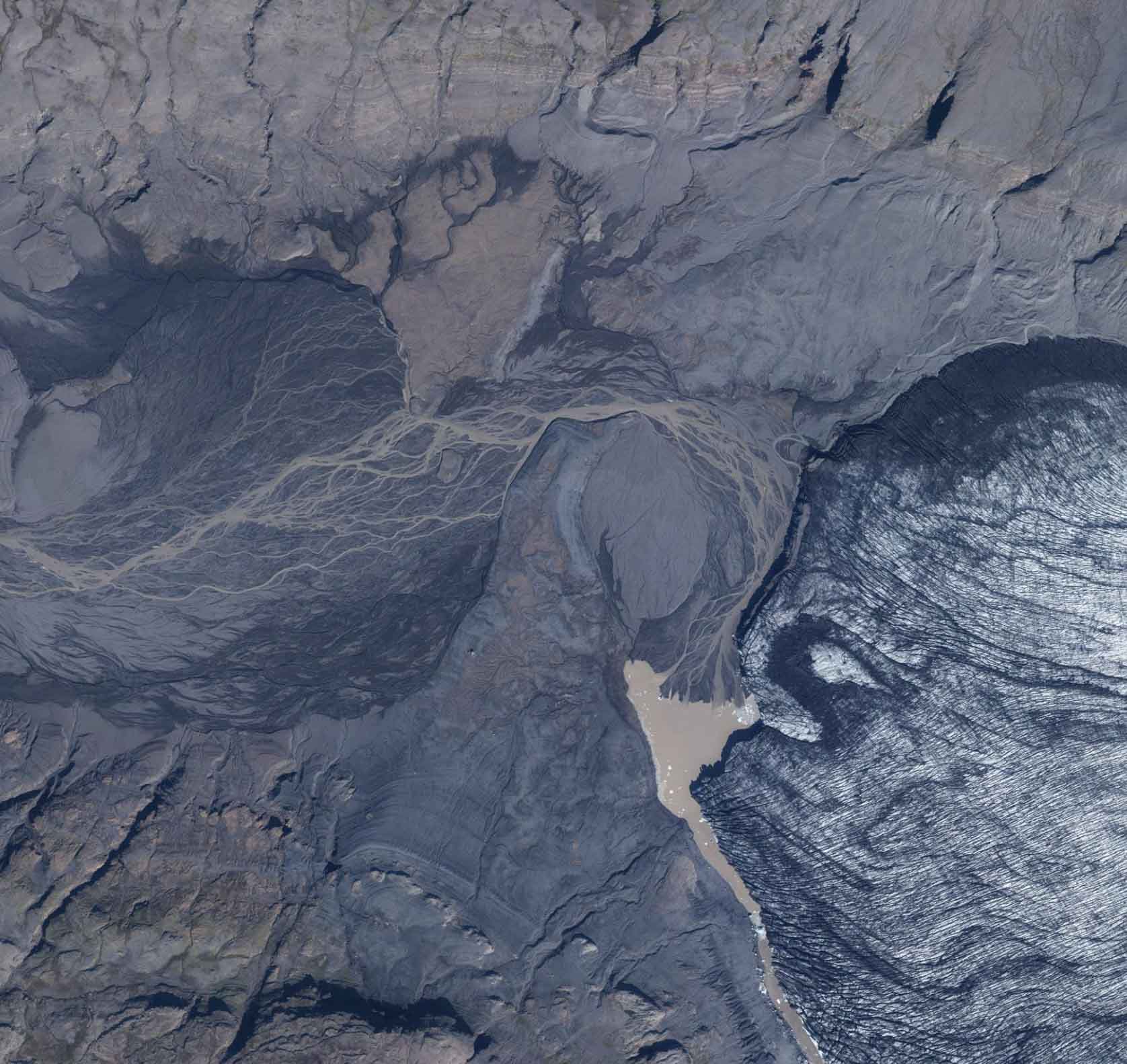

At present, the former lake bed of Grænalón is a plain where a braided river carries meltwater from Grænalónjökull towards Skeiðarárjökull. But things are about to change. At the moment the slope towards the glacier is very gently, thanks to Skeiðarárjökull. When the glacier recedes even further it will reveal a deep valley that’s now hidden beneath the ice. The river will choose a new path towards this deeper part and cut into the lake sediments of Grænalón, thus lowering the river bed and changing the landscape once again. Even now Grænalón is completely drained, the bottom is not yet in sight.

Search within glacierchange: