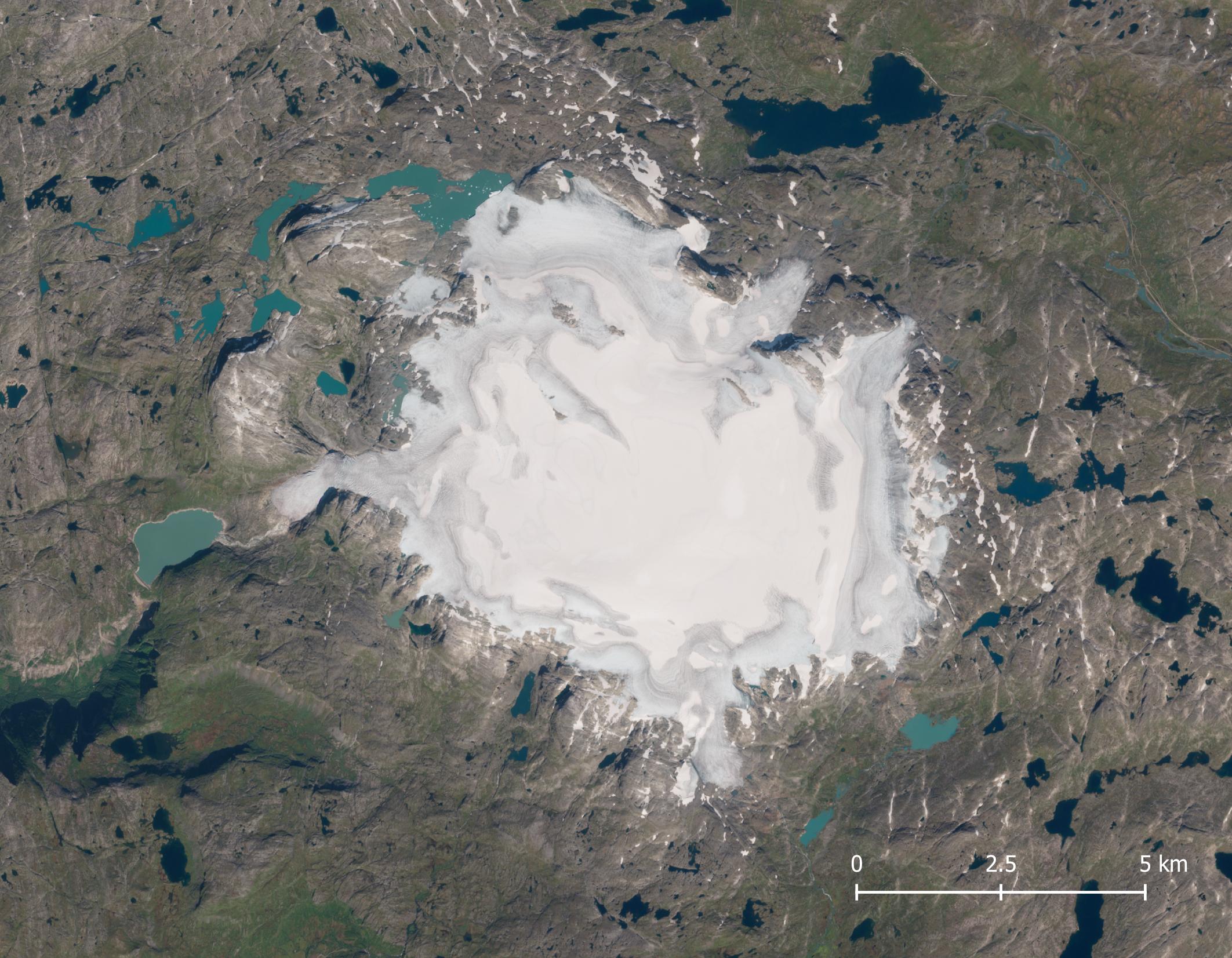

Where Europe’s biggest mountain plateau meets the deep fjords, there is an ice cap of sixty square kilometers named Hardangerjøkulen, Norway’s sixth largest ice cap. Hardangerjøkulen is probably not as well-known as the railway line passing its northern margin.

The Bergensbanen (mountain railway) connects the capital of Oslo to Norway’s second largest city of Bergen and was opened in 1909. Right next to the ice cap the railway has its highest station called Finse, which is also the country’s highest station and serves as a starting point for many hikes through the area. Finse station is also an ideal starting point for a tour around Hardangerjøkulen. Walking counterclockwise you first encounter Ramnabergbreen, a glacier terminating in a lake. The lake is yet to be named, as it used to be covered by ice. For now you can see icebergs drifting in the water, but it won’t be long before the glacier will withdraw completely from the lake.

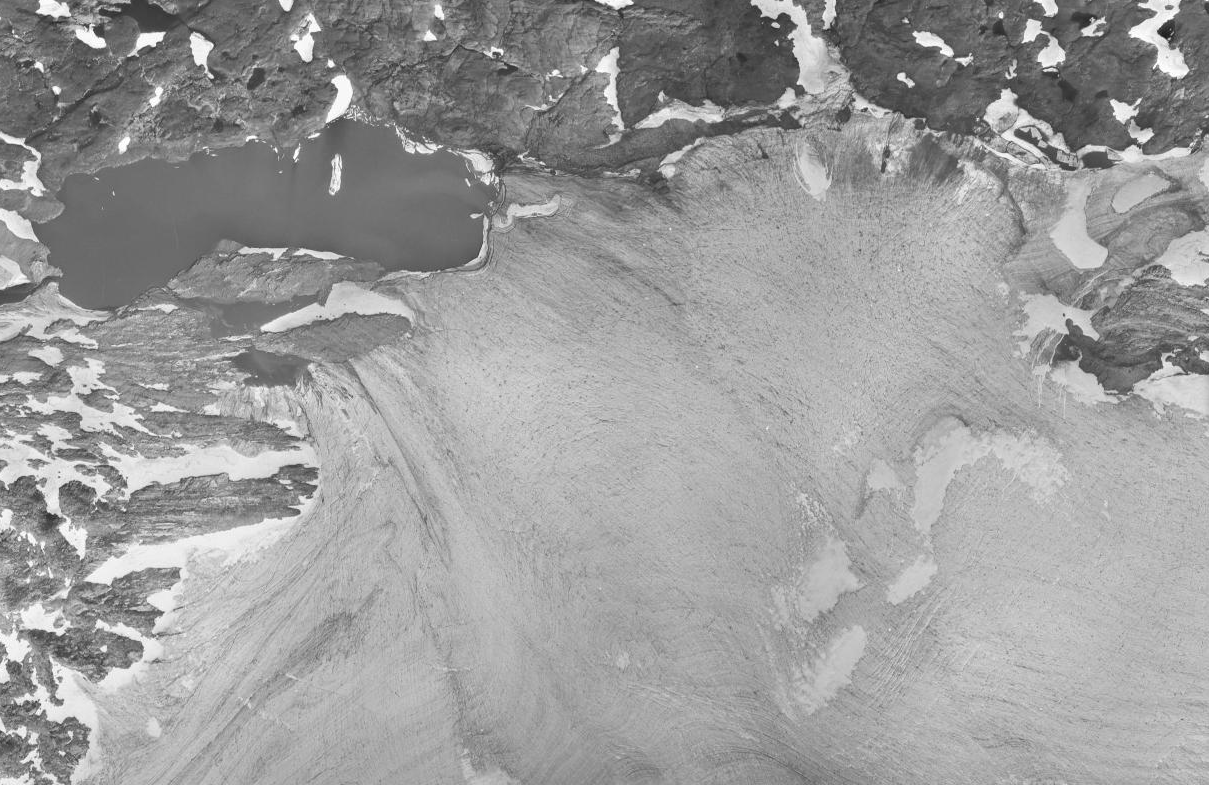

Ramnabergbreen in 1961 (left) and 2019. Source: norgeibilder.no

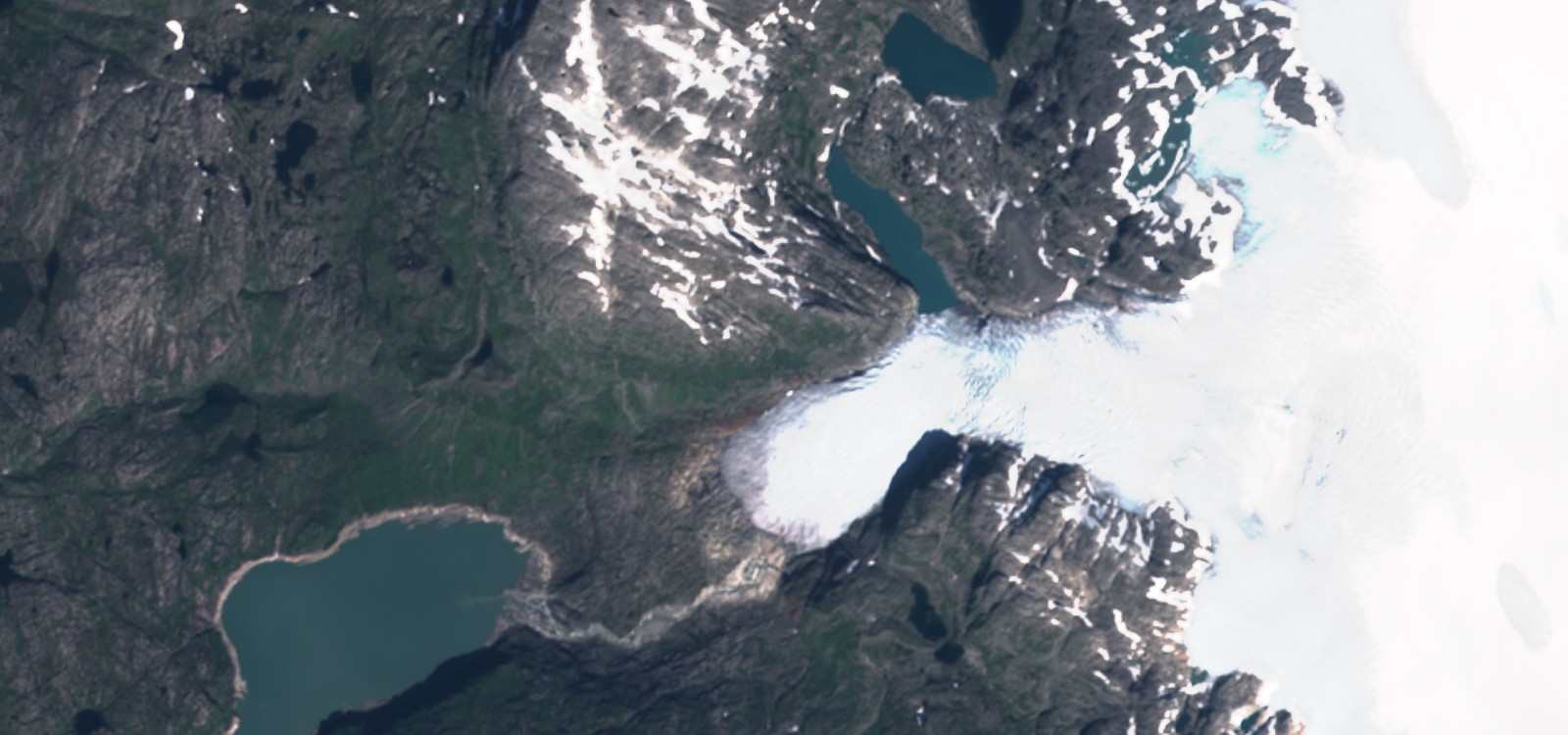

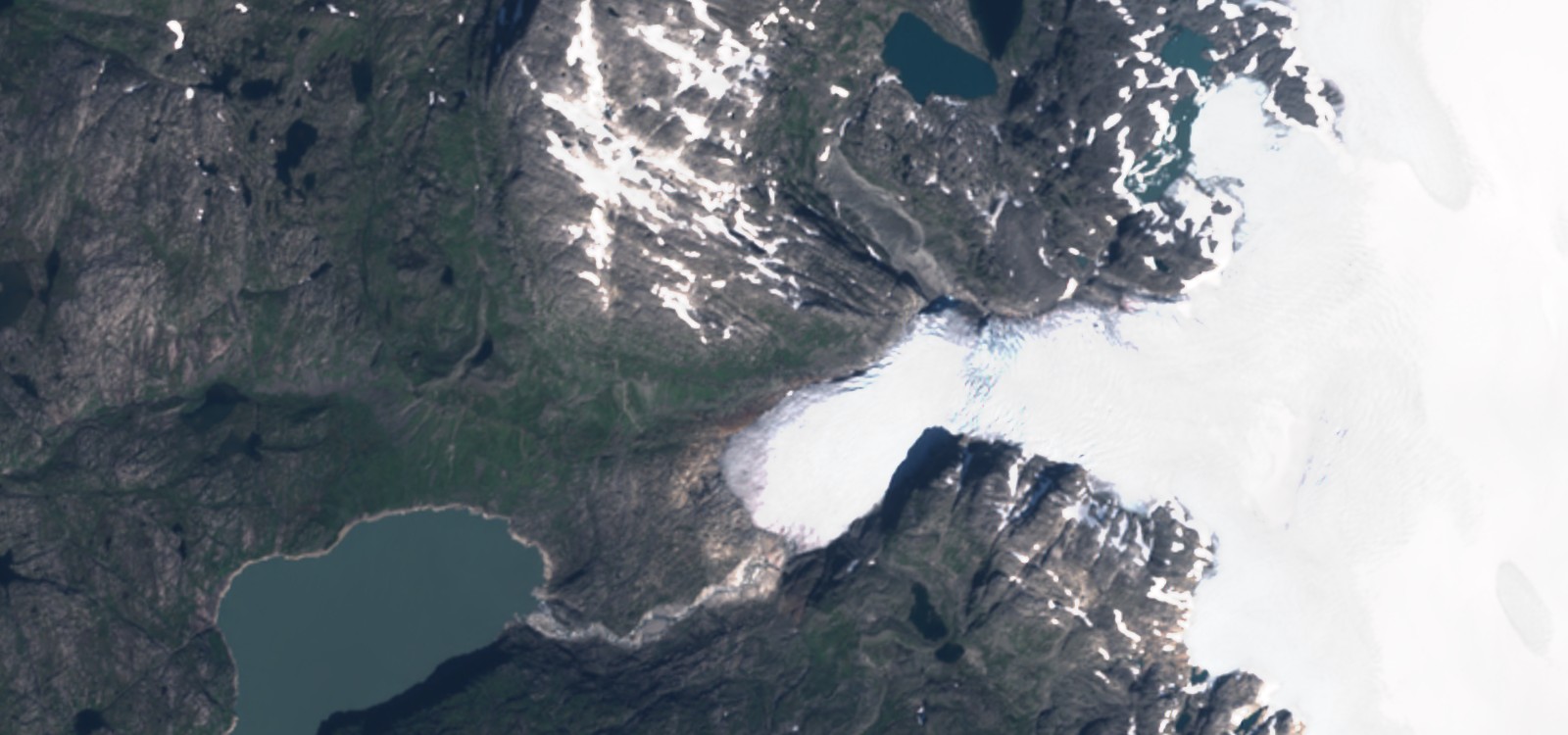

Nine kilometers ahead lies the Rembesdalskåka, a southwest facing outlet glacier. The glacier is relatively steep and thus full of crevasses. To the north, Rembesdalskåka dams a side valley, preventing water to escape. Only when the valley is sufficiently filled with water it bursts out from underneath the ice, causing small floods downstream.

Satellite image of Rembesdalskåka at 28-08-2022 (left) and five days later. The ice-dammed lake drained into the lower reservoir. Source: Sentinel-2.

The glacier-dammed lake fills every year and empties at the end of summer, when pressure has risen enough. Such glacial outburst floods happened usually in September, based on the years 2018-2022. But as a result of glacier thinning the ice dam gets weaker over time. In 2023 the lake hardly filled for the first time. Only in June the lake contained some water, but this was released the same month. A signal that of this special phenomenon will soon disappear completely.

From the southeastern part of Hardangerjøkulen two relatively unknown outlet glaciers flow down: the Vestra (Western) and Austra (Eastern) Leirebottsskåka. Although the western one is much bigger, the Austra Leirebottsskåka is the prettier one. It dives steeply from the ice plateau and is therefore full of crevasses. On top of that, it is closer to the trail rounding the Hardangerjøkulen.

From the railway station of Finse two glaciers are clearly visible: Blåisen to the left (east) and Middalen to the right (west). Leaving the train you can reach them within 1,5 hours and they are only one kilometer apart. That’s not to say they are similar. Blåisen is squeezed in between two steep mountain sides and ends on top of a chaotic plateau surrounded by debris. Middalen on the other hand is wide and smooth.

Hardangerjøkulen came into existence 4000 years ago, after having been absent for a few thousand years (Åkesson et al., 2017). The ice cap reached its maximum extend around 1750, when climate was relatively cold. Since then the ice cap lost half of its surface and outlet glaciers receded by 1.5 kilometers on average (Weber et al., 2019). The loss of area and length is increasing, so there is no future for Hardangerjøkulen: an increase in temperature by three degrees Celsius (relative to 1960-1990) is sufficient to make the ice cap disappear by the end of this century. If warming is limited to the present 2 degrees, Hardangerjøkulen will be around only a little bit longer (Giesen and Oerlemans, 2019).

Search within glacierchange: