Haugabreen (formerly known as Åmotbreen) is the main outlet glacier of Myklebustbreen.

Myklebustbreen is the seventh largest ice cap of Norway. It lies just west of Jostedalsbreen, which is ten times the size of Myklebustbreen. They are separated by Oldeskaret, a col 1100 m above sea level. A demanding but beautiful trail leads from Oldedalen to Stardalen valley through Oldeskaret.

Haugabreen is the only serious glacier arm of Myklebustbreen. Over its total length of about 6 km Haugabreen descends from the highest summit of Myklebustbreen (Snønipa at 1827 m) to just under 900 m. The otherwise relative smooth glacier surface is heavily crevassed at a steeper section around 1100 m. The snout is flanked by Kvannefjellet (1575 m) in the east.

On the other side of Kvannefjellet lies Flatebreen, a dying glacier that once reached all the way to the Oldeskaret col. A detailed study into the sediment load of Flatebreen’s meltwater revealed that the glacier has been more active over the last 800 years than during the preceding 8000 years (Nesje, 2001). That means Flatbreen was recently larger than in the preceding eight millennia. The terminal moraine from this maximum extent is very well preserved and lies right next to the trail.

A visit to Haugabreen usually starts in Stardalen. From Høyset farm a steep gravel road winds its way to a parking area at 630 m, close to the cabins of Haugastøylen. That’s where the trail to Oldeskaret starts, but another trail deviates from it after a kilometer. By then, the path already crossed multiple inconspicuous, though meaningful ridges.

The first of these ridges lies just beyond Haugastøylen. The path climbs a small mound, which represents the outermost moraine of Haugabreen. Once upon a time, the glacier came all this way. It’s safe to assume that this maximum occurred in the mid-18th century, like all other glaciers in the region and like has been demonstrated at Flatebreen. But to be sure, John Matthews carbon dated the soil beneath the outer moraine at multiple depths. He showed that the soil had been building up continuously for at least 7000 years and probably even 9000 years, until it was buried by the glacier in ‘recent’ times. This way, Matthews proved that Haugabreen hasn’t extended beyond its mid-18th century limit for many millennia (Matthews, 1980, 1991).

Many more ridges lie within the outermost moraine of Haugabreen. Following Haugabreen’s maximum size the glacier generally retreated, but occasionally experienced small readvances. In doing so, it pushed up about twelve new moraines. They line Haugadalen valley in front of Haugabreen like growth rings. Unfortunately, these moraines have yet to be dated.

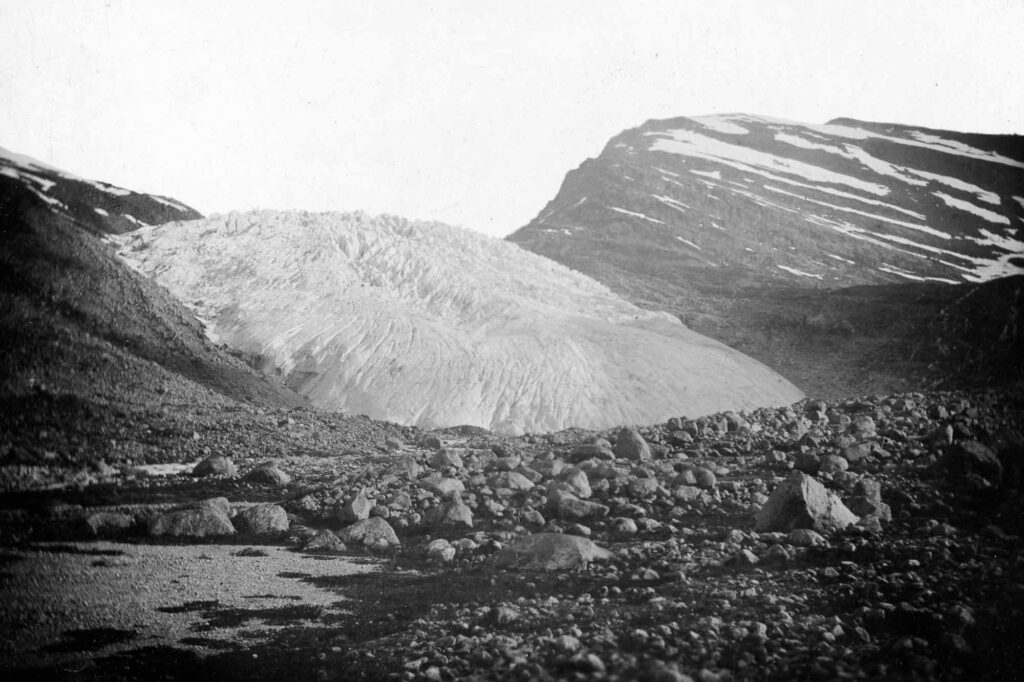

In the 1930’s the glacier retreated behind a steeper part of the valley and is no longer visible from Haugadalen since then. In this steep, rocky section of about 150 m high no moraines are preserved. It’s also the hardest part of the climb to Haugabreen, which is nonetheless an easy hike for Norwegian standards.

The front of Haugabreen has now retreated into flatter terrain, some 500 m from the rocky slope. That makes the ice approachable and glacier hikes are therefore organized here. It’s one of the more quiet area’s to participate in a guided walk over the surface of a glacier and learn about the ice. Half a kilometer up-glacier the steepness increases again and the ice becomes full of transverse crevasses.

Though Haugabreen isn’t as closely monitored as some nearby glaciers, it’s clear that the glacier advanced in the 1990’s (parallel to other glaciers in western Norway). A ’fresh’ moraine namely lies 300 m in front of the present-day glacier margin.

Haugabreen probably receded again from the early 2000’s onwards. Over the past years Haugabreen shrank around 25 m per year (NVE). In this pace Haugabreen could lose its accessible snout within 20 years. The glacier will retreat beyond a bedrock bump (where the transverse crevasses now are). By then, Haugabreen is out of reach to ordinary hikers and Norway will have lost yet another location for glacier hikes.

Haugabreen in 2007 (Daniel Saakes via Facebook) and 2024.

Search within glacierchange: