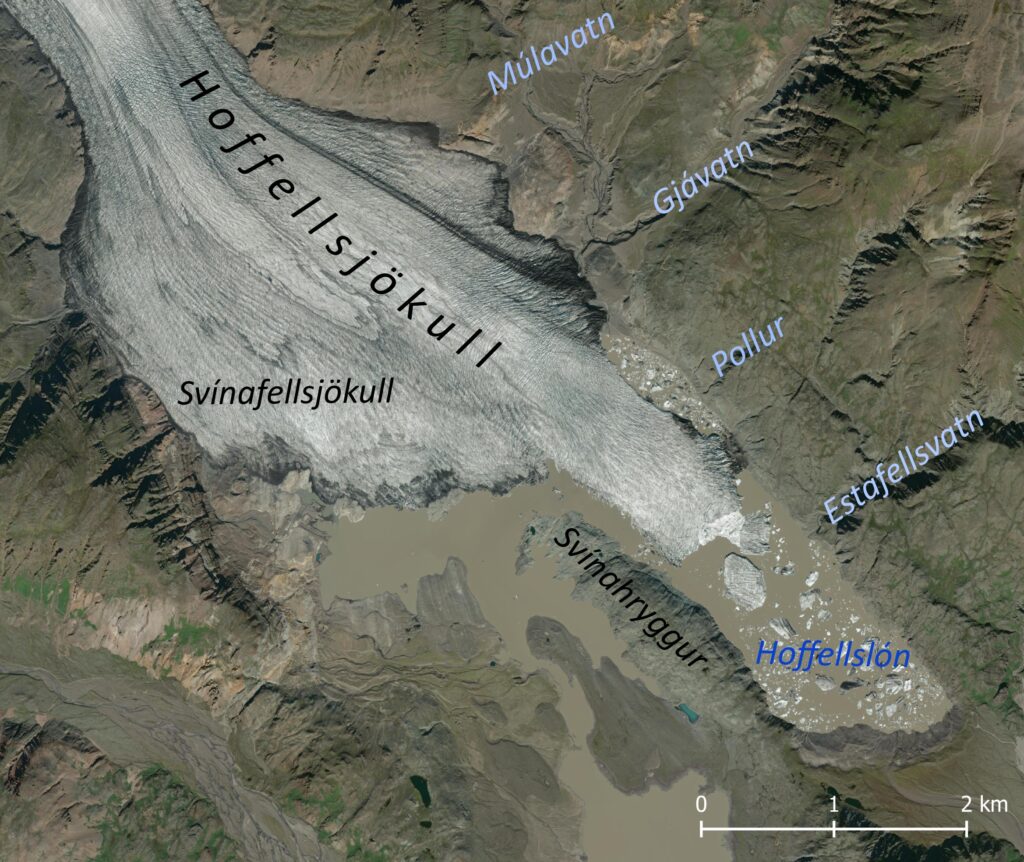

Hoffellsjökull is a south-facing outlet glacier in eastern Vatnajökull. Its large snout is falling apart in an expanding lake.

The upper part of Hoffellsjökull is located between the subglacial mountain ranges of Breiðabunga in the west and Goðahnúkar in the east. From both areas, an ice stream flows on either side of mount Nýjunúpar before merging downflow. The glacier then passes an icefall with a speed of 400-500 m a year (Aðalgeirsdóttir et al., 2011). Below the 1.2 km wide icefall, the glacier fans out into a lobate snout.

The snout is subdivided into two glaciers. Its broader western part is called Svínafellsjökull, after the prominent mountain in front of the glacier. The eastern part continues as Hoffellsjökull, its name derived from the settlement downflow. This part is more elongated, because it is confined to a narrow valley. In older times, both branches were separated from each other by Svínahryggur ridge, also known as Öldutangi. When the glacier had its largest extent during the 1800’s, the ridge wasn’t visible at all.

Four ice-dammed lakes existed along the eastern margin of Hoffellsjökull. The northernmost lake was Múlavatn. It was often connected to Gjávatn, the second lake. One kilometer to the south was Pollur, a much smaller lake. And closest to the snout lay the fourth lake (Efstafellsvatn), where the river Efstafellsgil bumped into Hoffellsjökull (Björnsson, 1976). It disappeared already around 1950 because of glacial thinning. Gjávatn emptied for the last time in 2015 in a dramatic way (Guðmundsson et al., 2015). Múlavatn drained permanently one year later, but it had already considerably reduced in size. By now, there are no ice-dammed lakes left.

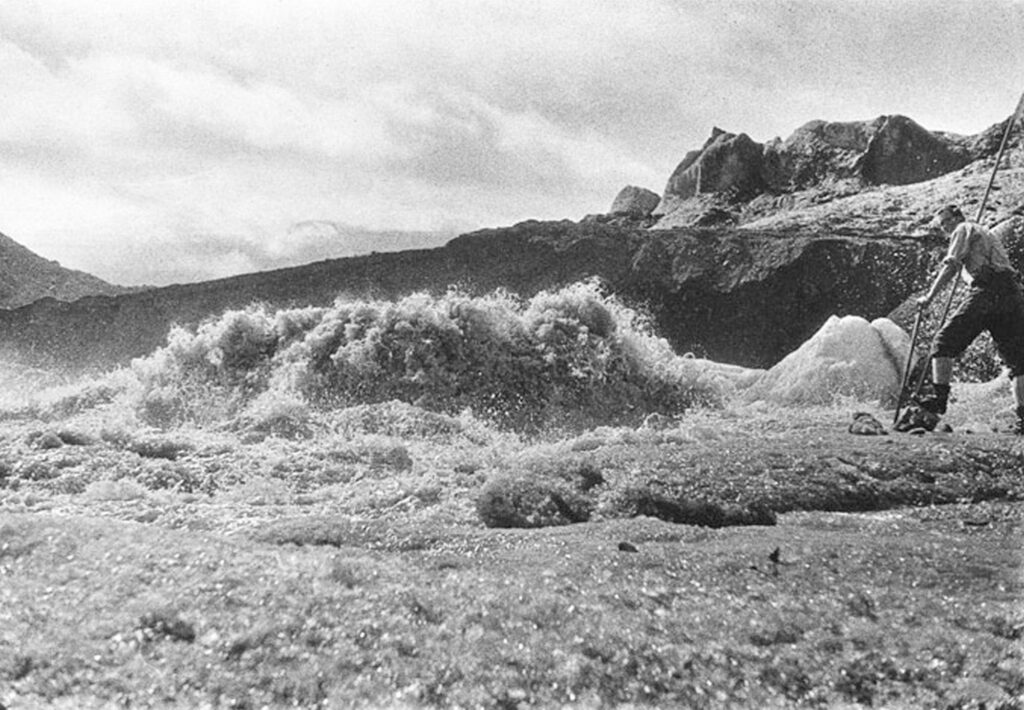

Each time one of the lakes burst out when its ice dam gave way, a powerful wave of water rushed over the glacier’s bed. With every such jökulhlaup, large amounts of sediments were removed and deposited at the outwash plain in front of Hoffellsjökull. Together with the erosive power of the huge glacier, the valley floor was lowered in the course of a few centuries to a depth of 300 m below sea level. Such a glacier-ploughed depression is called an overdeepening.

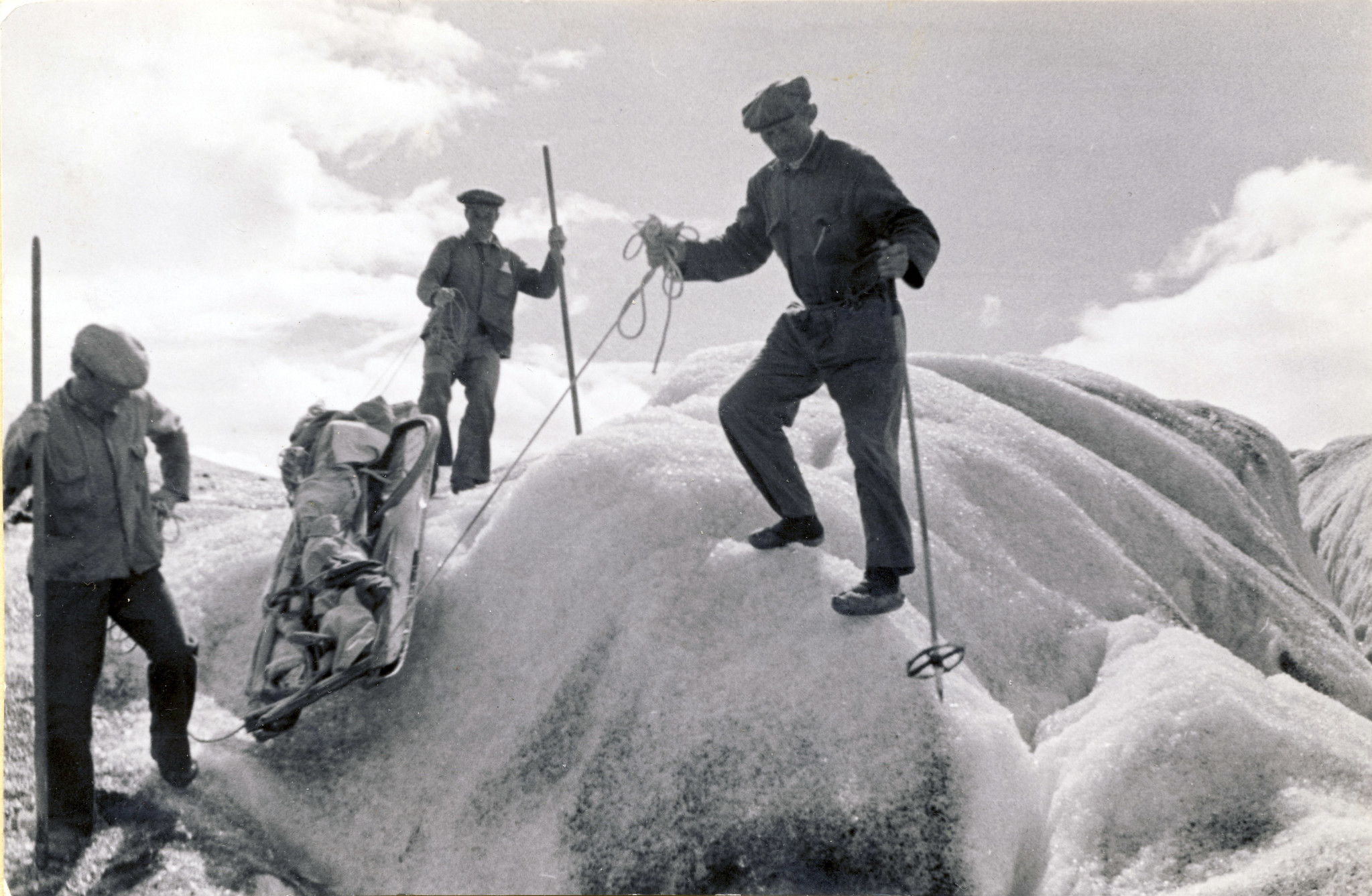

The glacier still completely filled the overdeepening when a Swedish-Icelandic expedition studied Hoffellsjökull very closely in 1936-1938. On the basis of its flow regime, mass balance, local climate and topography, the researchers got a much better understanding of the behavior of the southern Vatnajökull outlet glaciers. As part of these activities, Sigurður Þórarinsson made valuable photos of Hoffellsjökull. He later became a famous glaciologist. Even though Sigurður couldn’t see the depth of the valley, he knew it had to be deep:

‘’An enormous mass of water wells up almost vertically in front of the ice margin, which indicates that it is squeezed out under great pressure, and that the sandur plain in front of the glacier is considerably higher than the base of the glacier (Thorarinsson, 1939:204).’’

Because of the sheer thickness of Hoffellsjökull, it took many years before it actually started receding. It wasn’t before circa 1950 that some room was created between the glacier and its outwash head for a small lake to appear. This was the start of Hoffellslón. But it took another 50 years for the glacier snout to really abandon the outwash head. In fact, its stability over the course of the 20th century is unique for southern Iceland (Evans et al., 2019), notwithstanding the fact that it lost over 250 m in thickness (Hannesdóttir et al., 2015).

Hoffellsjökull in 1953 (left) and 2023. Note the lowered water level. Photo 1953: Björn Björnsson, Þjóðminjasafni Íslands nr. BB1-1879.

How different was the evolution of Svínafellsjökull, the part of Hoffellsjökull to the west of Svínahryggur. It gradually receded throughout the 20th century, creating push moraine sequences in winter and during periods of stability or readvance. The reason for their different behavior is that Svínafellsjökull wasn’t confined to a valley and slides over harder bedrock, therefore didn’t erode an overdeepening and could subsequently oscillate more freely instead of only thinning/thickening. In total, the glacier receded close to 5 km since 1890.

The main meltwater river of Hoffellsjökull had ‘always’ been Austurfljót to the east of Svínahryggur. It was the source of this river that Þórarinsson saw boiling up at the edge of the glacier. After all those jökulhlaups that deposited sediments in front of the glacier, the foreland of this part of the glacier was more elevated than that of Svínafellsjökull. But due to the bed topography, most meltwater had no other choice that to escape from the glacier here. Until 2008.

Because most water for forced into Austurfljót, the river on the western side of Svínahryggur, Suðurfljót, had always been much smaller, even though its foreland was lower. But in 2008, everything changed rapidly. After decades of glacier thinning, meltwater could suddenly bypass Svínahryggur in the north and flow towards Svínafellsjökull. In a matter of days or weeks, Suðurfljót became the only river that drained the entire Hoffellsjökull. Austurfljót completely ceased to flow due to a fall in lake level of Hoffellslón, the lake in front of Hoffellsjökull (Evans et al., 2019).

Hoffellslón will grow much larger: the overdeepening runs all the way to the base of the icefall, 5 km from the present glacier front. How fast the glacier will retreat is hard to say and easy to underestimate. Both Svínafellsjökull and Hoffellsjökull are retreating into deeper waters, which make them susceptible to collapsing. The glacier can calve and break up as it floats above the deepest part of Hoffellslón, like it did in 2010 (Evans et al., 2019). In 2023, 400 m long parts of the glacier broke off as well.

Eventually, even the top part of Hoffellsjökull will disappear. Although the ice surface is at a save 1200-1300 m, the bedrock doesn’t reach above a 1000 m. That isn’t high enough for snow to be preserved through summer, so it’s only thanks to the thickness of the ice itself that the glacier can survive. But as more ice will be drawn down now that the slope steepens due to ice loss, even the uppermost surface will lower. Add a bit of global warming, and Hoffellsjökull will inevitably vanish.

Search within glacierchange: