Mýrdalsjökull ice cap sits on top of Katla volcano. The crater rim is lowest in the east, so most ice flows out in that direction. That’s the start of Kötlujökull, an impressive glacier.

Katla’s elliptical crater has a diameter of 14 km and is completely filled with ice up to 700 m thick (Björnsson et al, 2000). Once the glacier has left the caldera, Kötlujökull continuous to flow for another thirteen kilometers and terminated two hundred meters above sea level. On its way down the glacier has to pass a relatively narrow valley three kilometers wide, after which it fans out and forms a piedmont glacier. This more or less circular glacier type forms when the ice is no longer laterally constricted and can flow out in all directions.

Katla frequently erupts: twenty times in the last thousand years. Its magma melts ice like crazy and causes gigantic glacial floods known as jökulhlaups. Nowhere in the world is this natural phenomenon as powerful as in Iceland, specifically Katla. Up to three hundred thousand cubic meters of water is released each second, washing everything away on its path to the sea.

As soon as the first Scandinavian people set foot on Icelandic soils, they were confronted with the forces of Katla. The settlers interpreted its plume of ash full of lightning, landslides and flash floods in contemporary ways. A housekeeper named Katla was believed to have ran up the volcano wearing magic breeches, dived into the crater and thereby triggering an eruption. Also, man with magical staffs led the water by means of witchcraft away from their farms. People were even believed to have survived on icebergs drifted out to open sea (Björnsson, 2017:223). Although these saga’s no longer hold any truth, they help in dating Katla’s eruptions in the first centuries after settlement.

Since the time of settlement Katla erupted more or less every fifty years, breaking through the ice cap and causing jökulhlaups. Almost all floods rushed down the Kötlujökull eastwards. Frequent jökulhlaups prevented vegetation to grow on the plain between the glacier and the sea called Mýrdalssandur. Despite the fact that Katla hasn’t erupted since 1918, the Mýrdalssandur is still largely deprived of plants due to poor soils and battering sand storms. Plants only grow where they have been actively planted, like alongside the ring road. This has greatly reduced the number of days on which traffic has to be stopped due to blinding sandstorms.

While Kötlujökull is awaiting the next devastating eruption, climate change is eating him away bit by bit. Just like most glaciers in (southern) Iceland Kötlujökull is shrinking since the start of the twentieth century, only interrupted by a short-lived period of growth in the 1980’s. Research shows Icelandic glaciers experienced their Holocene maximum extent in the nineteenth century, but Kötlujökull doesn’t quite fit the image. By dating the moraines using tephrochronology (technique using ash layers in the soil profile to date its age) researchers showed Kötlujökull’s outermost moraines were pushed up at the start of the fifth century AD (Schomacker et al., 2003). They extent a whopping two kilometers beyond the nineteenth century ones.

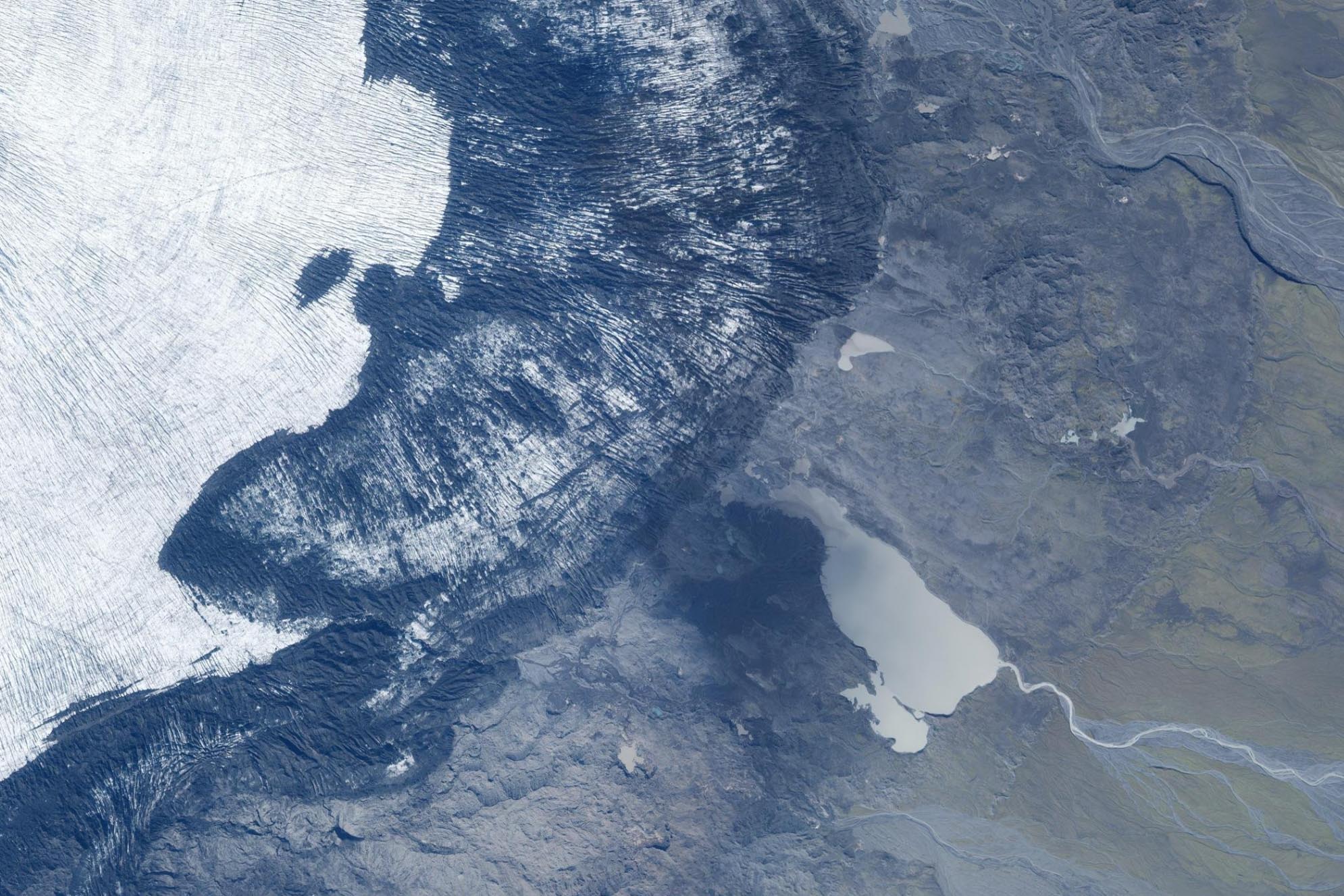

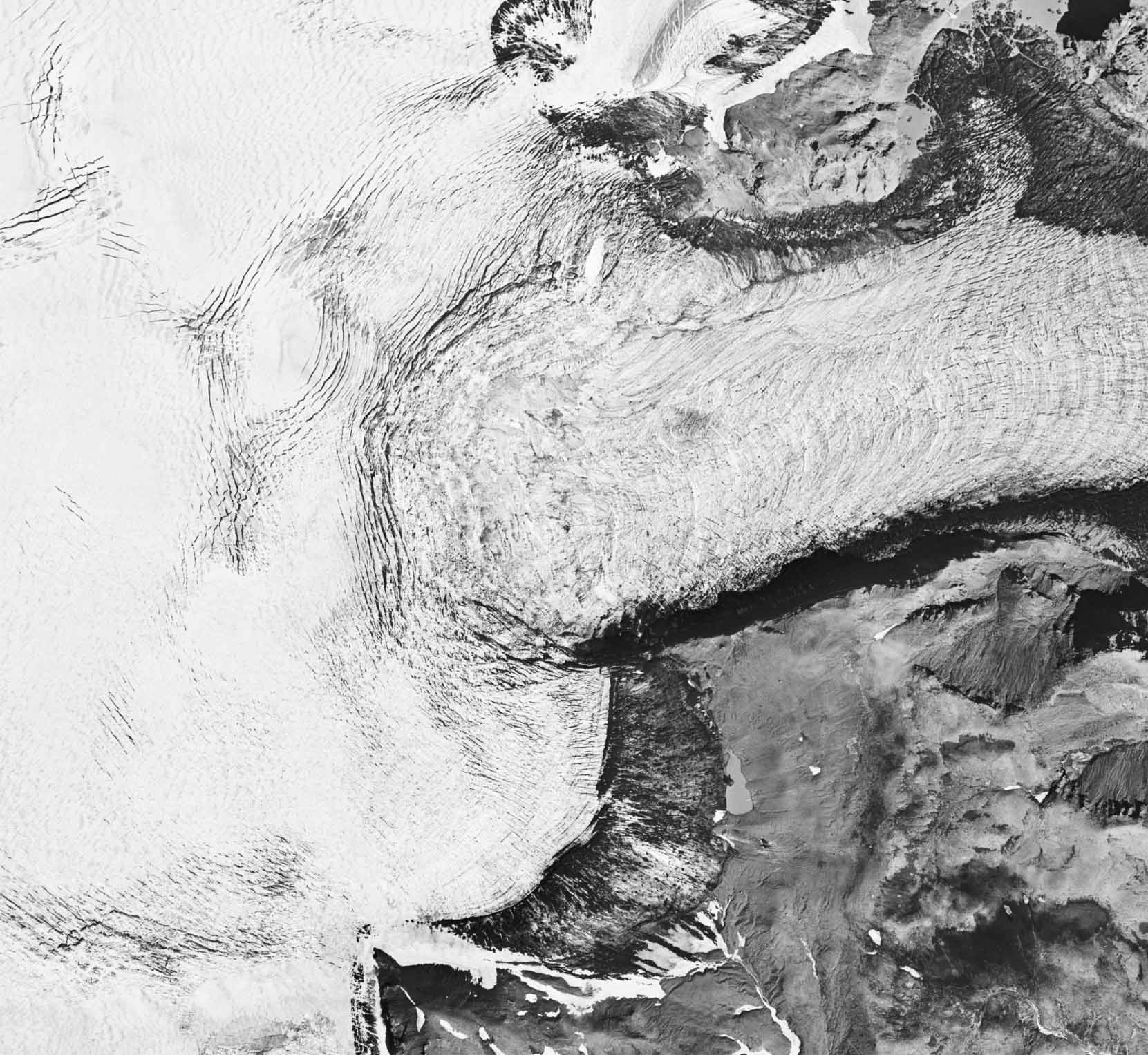

Orthophoto of Kötlujökull in 1996 (left) and 2020. Source: Landmælingar Íslands.

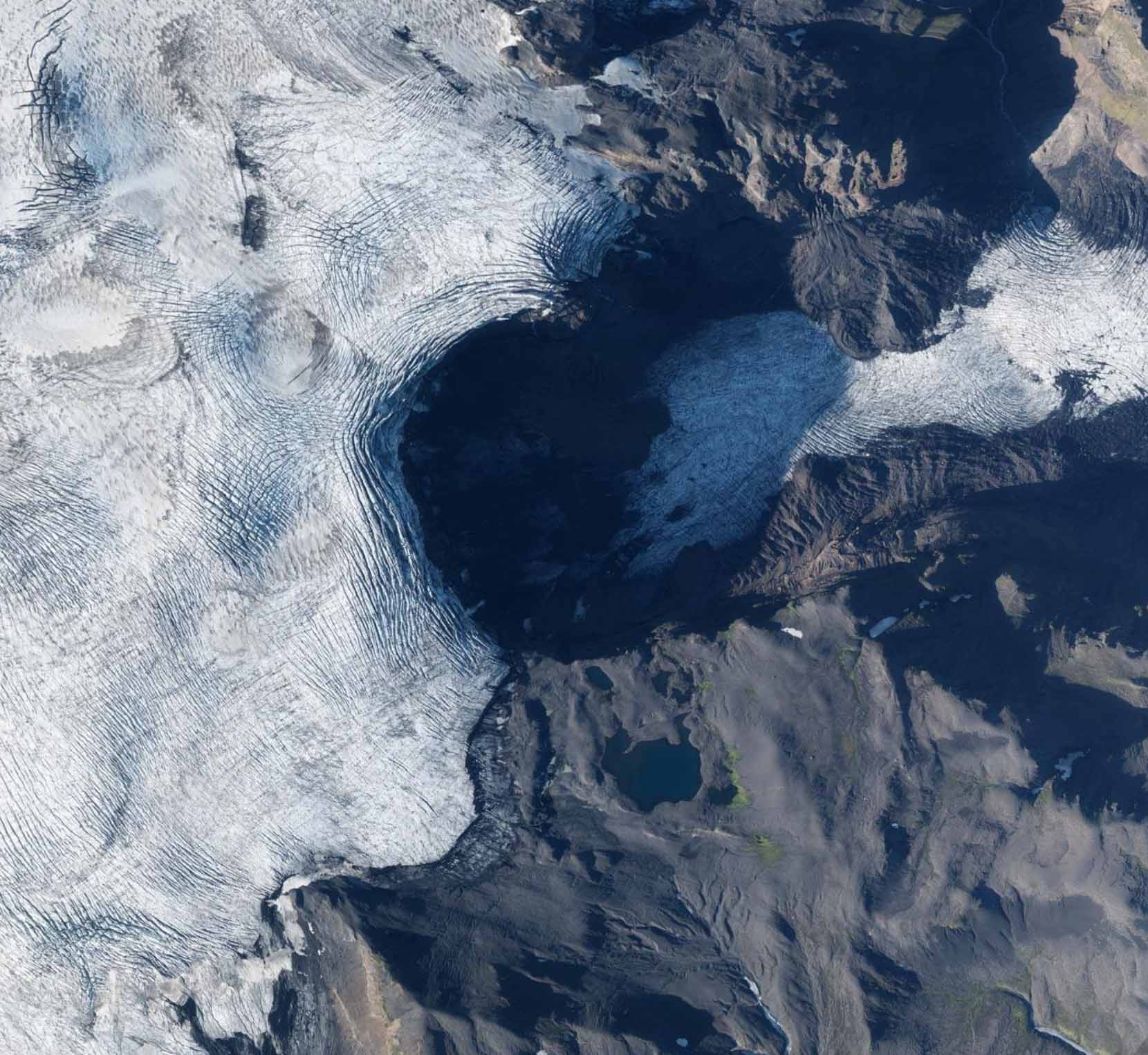

Orthophoto of Huldujökull in 1996 (left) and 2020. Source: Landmælingar Íslands.

Over the last thirty years Kötlujökull receded 1 to 1.5 kilometer. The southern ice margin receded much less though, because it is covered by an insulating layer of debris that slows down melt. Several tour companies gratefully use this patch of non-moving dead ice, decoupled from the rest of the glacier. They organize excursions into the drained meltwater tunnels inside the glacier. Safely, as the ice no longer moves.

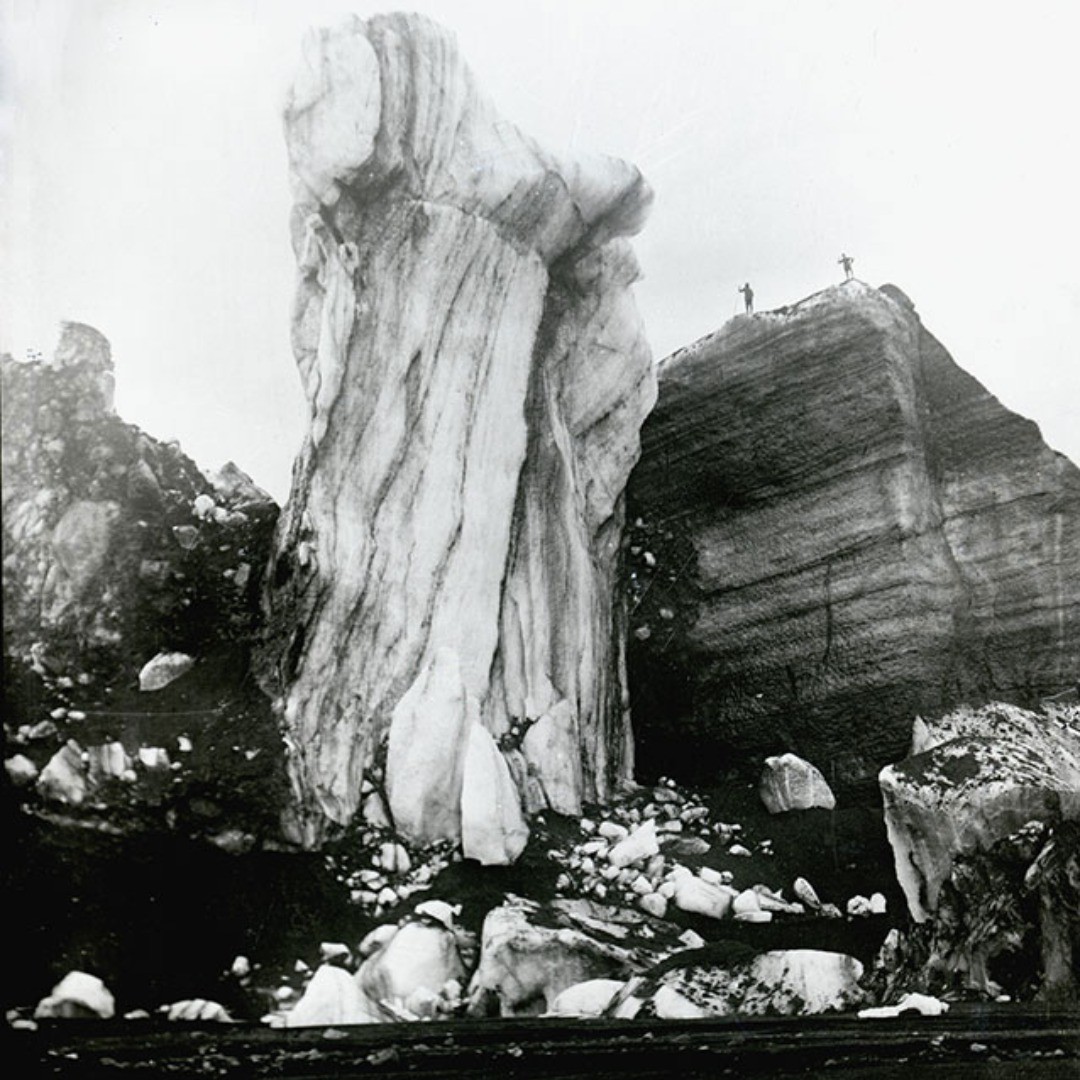

Another place where the ice is virtually stagnant is at Huldujökull, a small tributary of Kötlujökull. Nowadays ice tumbles down a vertical cliff onto the Huldujökull below, but as recent as the start of the 21st century no bedrock was visible. The glacier flowed uninterrupted down and supplied Kötlujökull with ice. In just twenty years the glacier has been replaced by a spectacular waterfall. One of many ways in which ice is replaced by water.

Search within glacierchange: