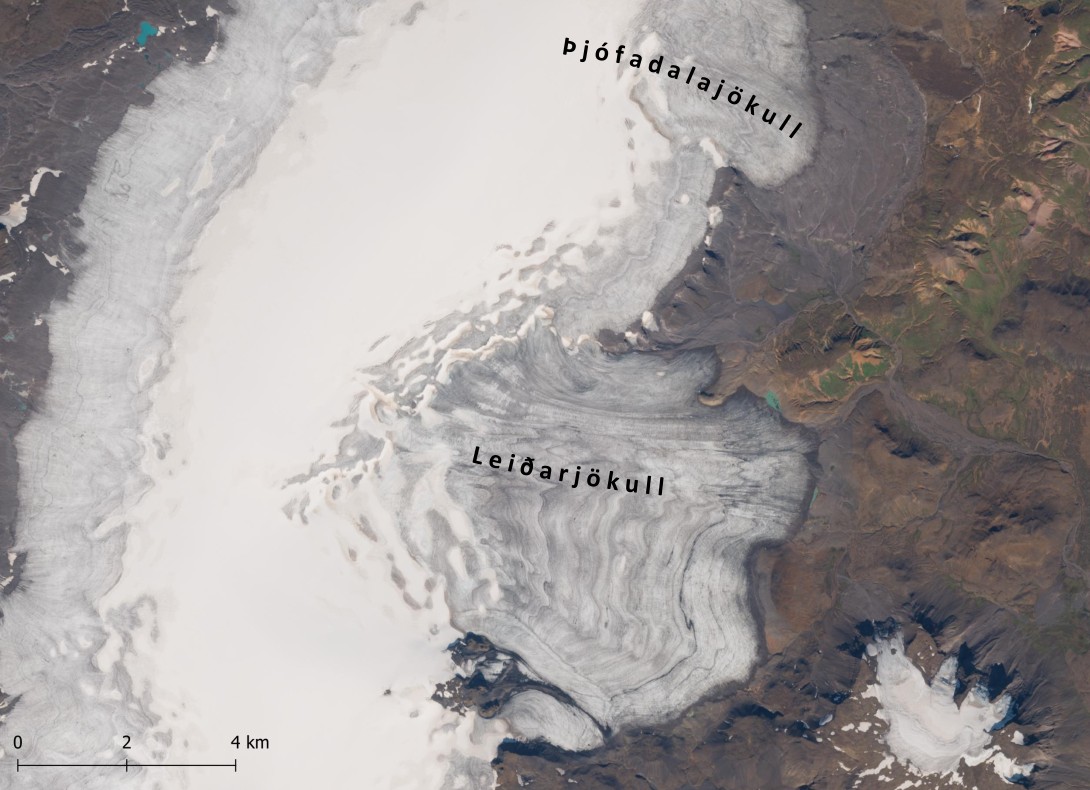

The Leiðarjökull is a wide glacier in the northeastern part of Langjökull. It descends from an altitude of 1400 meters to 800 meter, where the snout is wide and quite flat.

The snout of Leiðarjökull is eight kilometer wide and up to four hundred meters thick. Below it lies an old volcanic crater (Björnsson and Pálsson, 2020). Leiðarjökull hardly moves: the relatively steep part at an altitude of 1200 m has an yearly velocity of forty meters, but the lower and flatter it gets the more it decelerates. At the glaciers margin, ice velocity is no more than ten meters annually (Palmer et al., 2017).

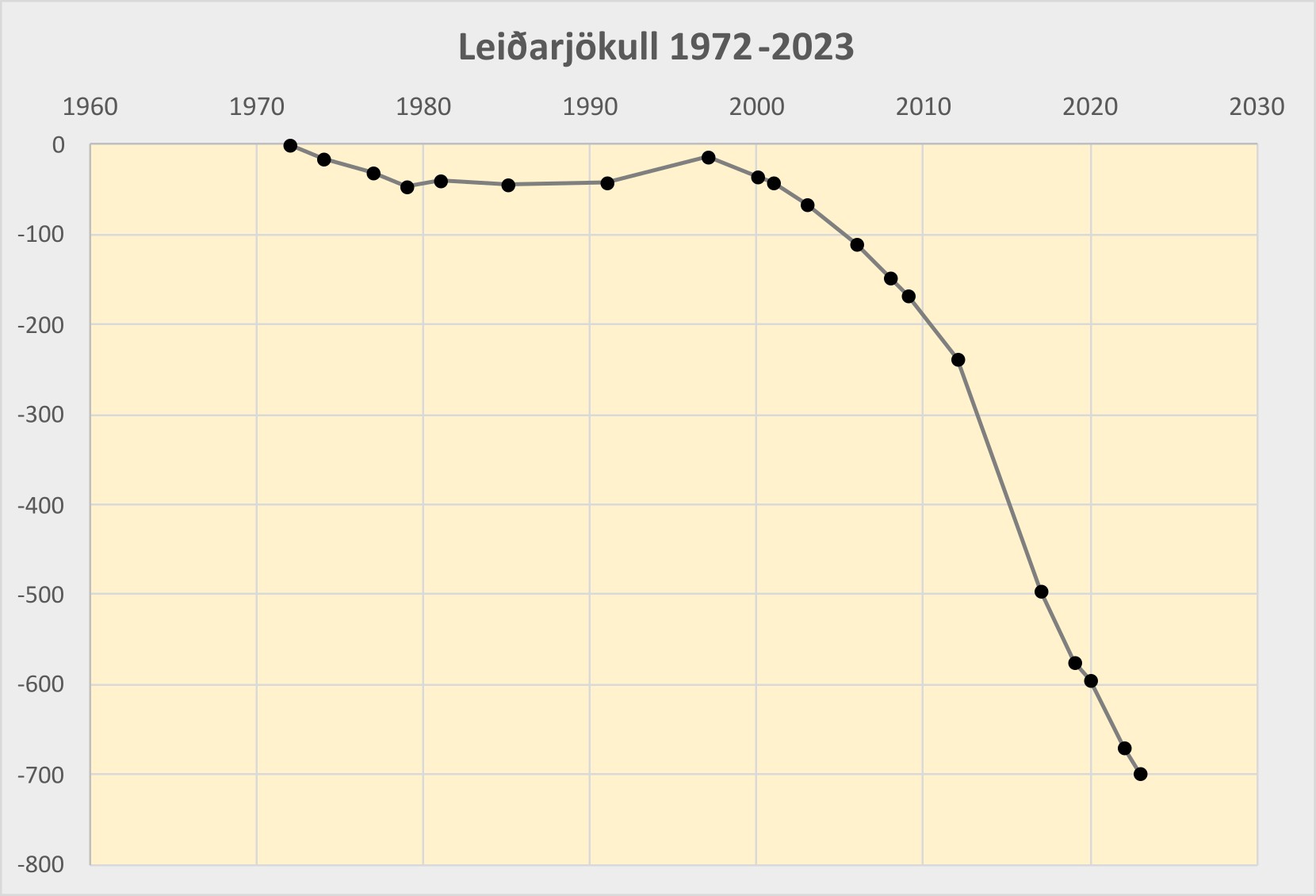

The entire Langjökull ice cap has shrunk over the past century, but there are regional differences. Its southern glaciers lost four kilometers of length, a lot more than their northern counterparts. Leiðarjökull is only half to one kilometer shorter than it was at the end of the nineteenth century. Remarkably, this does not mean Leiðarjökull is melting at a slower pace than other parts of the ice cap. The glacier is simply much thicker than other parts of Langjökull, so it takes longer to make it disappear.

Along the Leiðarjökull runs the Kjalvegur. Though this name nowadays (also) refers to mountain road F35, it is much older. The old Kjalvegur lies closer to the ice cap and was used by travelers with horses and flocks of sheep, for trade on the other side of the island. When walking the Kjalvegur, traces of all those animals are easily recognized in numerous trails running parallel to each other. While the present-day F35 runs through a barren landscape deprived of vegetation, the old Kjalvegur crosses a much richer landscape, as cattle needed to to graze on their way.

About halfway the Kjalvegur you stumble upon the Þjófadalir, a sheltered valley close to the Leiðarjökull. The valley is separated from the glacier by the Rauðakollur, at 1065 m the highest non-glaciated mountain in the area. From its top there is a magnificent view over Leiðarjökjull and Þjófadalajökull to its north. Þjófadalajökull is much thinner and lost therefore more of its area than Leiðarjökull.

Leiðarjökull and Þjófadalajökull in 1927-1929 (left) and 2023. Photographer: Hans Kuhn, National Museum of Iceland, Lpr/2003-576-21.

Meltwater from Leiðarjökull and Þjófadalajökull runs to the south as Fúlakvísl river. It empties over thirty kilometer downstream in the Hvítarvatn, where Fúlakvísl forms a rich delta of sedges and heath by depositing glacially eroded sediments. The delta attracts lots of breeding birds, especially pink-footed geese.

Despite the varied and colorful landscape, very few tourist are tempted to walk the three-day hike over the old Kjalvegur. Most of them stick to driving around the island, and if they make time for a multiple-day trek at all, it’s always the Laugavegur between Þorsmörk and Landmannalaugar. For Icelanders, Kjalvegur remains their little secret.

Search within glacierchange: