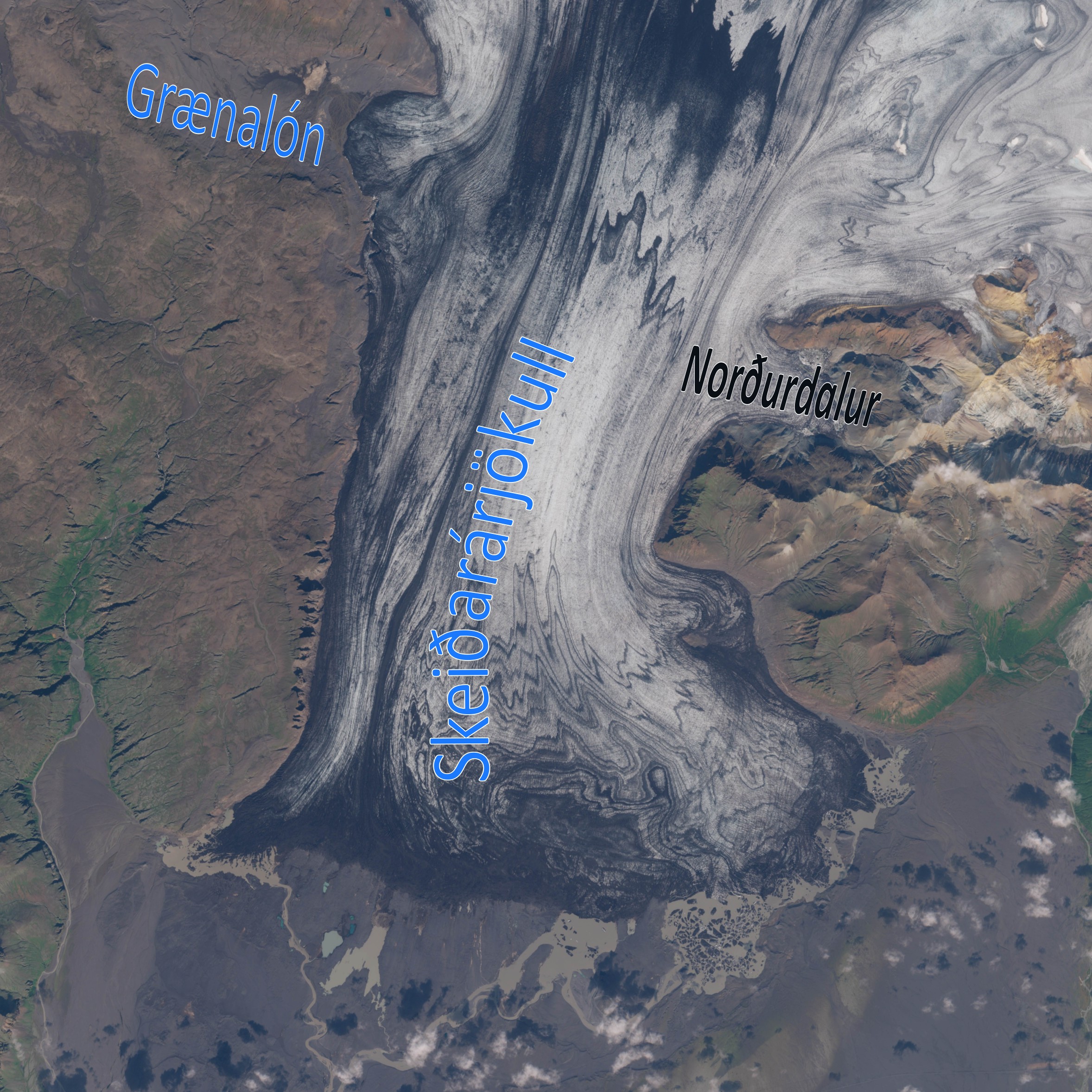

Norðurdalur is a short but wide valley along the eastern margin of Skeiðarárjökull. A glacial lake occupies this remote valley. Every summer the lake drains, but this is hardly noticed anymore due to drastic landscape changes.

Skeiðarárjökull is among the best studied glaciers in Iceland. Most attention is focused on jökulhlaups: floods of meltwater caused by volcanic eruptions or sudden outbursts of glacier-dammed lakes. By far the biggest jökulhlaups at Skeiðarárjökull emanate from Grímsvötn, a volcanic system and subglacial lake, but in the case of a smaller flood there are two other suspects: glacier-dammed Grænalón at the western margin of Skeiðarárjökull and Norðurdalur at the opposite side. While Grænalón no longer exists, the much smaller glacial lake in Norðurdalur is still active.

Where Skeiðarárjökull passes the Norðurdalur, the glacier is ten kilometers wide. A fraction of its ice is directed towards the two kilometer long valley of Norðurdalur. The ice reaches the surrounding hill slopes, but in the outer corners of the valley creeks flowing towards Norðurdalur have always created small lakes. Due to global warming these lakes are growing larger.

Norðurdalur is surrounded by the mountains of Skaftafellsfjöll. On their slopes there are horizontal lines, demarcating former lake levels. The upper line is an impressive 150 m above the present-day lake, meaning Skeiðarárjökull is that much thinner than before. Even here, 15 km upstream from the glacier snout, climate change is not to miss.

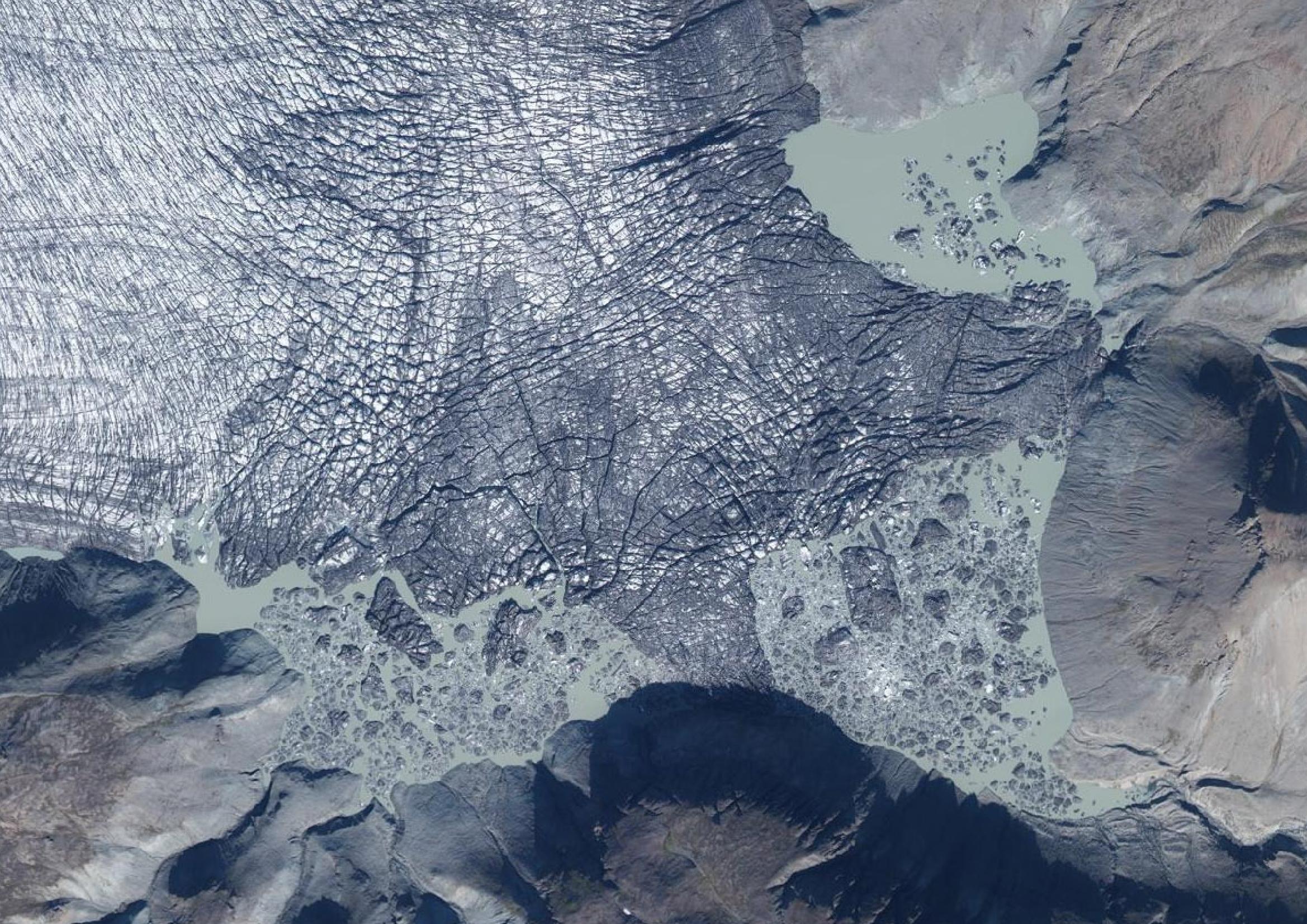

Climate change influences the lake volume in two opposing ways. On the one hand, higher temperatures melt more ice, thus enlarging the lake. Indeed, the small lakes in the corners of the valley are becoming more and more interconnected. On the other hand, thinning of Skeiðarárjökull lowers the maximum water level. Therefore, jökulhlaups (floods) from Norðurdalur have never really been dangerous. Often, the lake empties unnoticed. The lake fills with meltwater during spring and summer, to release its water again when water pressure is sufficient to find a way underneath the glacier. Because of this cycle, jökulhlaups occur almost every year, normally towards the end of summer. Recently it happened in September 2017, September 2018, July 2019, August 2020, August 2021, July 2022 and August 2023. Upon flooding, the lake erodes such an effective drainage path that it can only refill after winter, when everything is frozen up and compressed again.

Orthophoto of Nordurdalur in 1997 (left) and 2017. Source: Landmaelingar Íslands (1997) and Loftmyndir ehf.

Next time Norðurdalur will drain, the rushing water will pass a rapidly changing landscape. Until the start of the 21th century there was a second area downstream where water could also collect, for example. This lake, like Norðurdalur located in between the glacier and Skaftafellsfjöll, was filled by the Langagil, a river that is now deeply incised into the lake deposits. In December 2021 the lake was filled for one last time, because a part of the water released from Grímsvötn spilled here.

Because of continued thinning of Skeiðarárjökull a hill is appearing from underneath the ice. This fell doesn’t have a name, but it might once had. At the time of settlement over a thousand years ago, glaciers were smaller and this fell must have been visible. Therefore it could be the same fell that Landnáma (The book of settlement) refers to as Jökulfell (Skaftafell Geology facebook-page). Until the year 1343 there also was a small church close by. When glaciers advanced, the fell was submerged in ice and its name transferred to a neighboring mountain. Maybe it can be renamed once the rock is fully uncovered again.

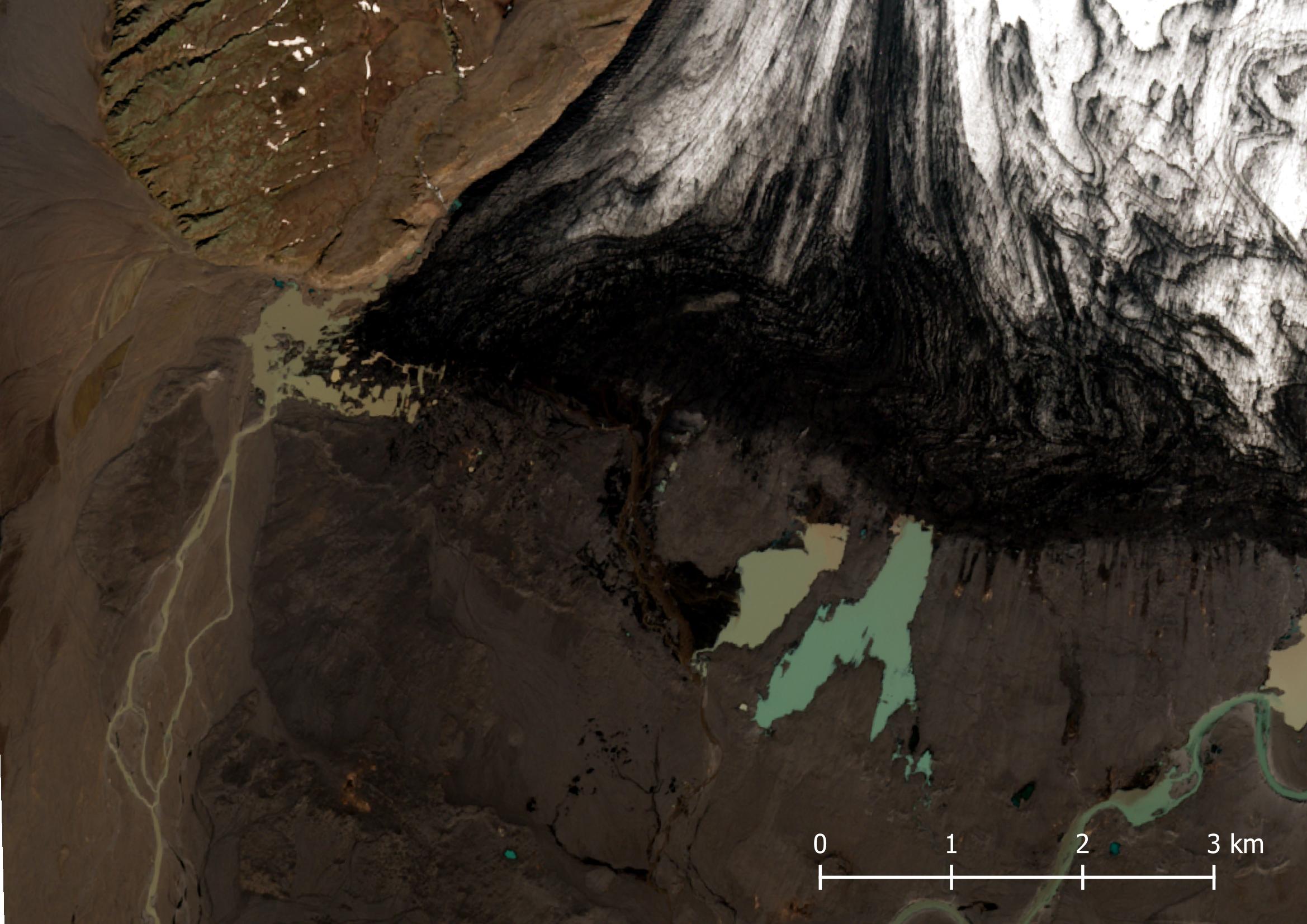

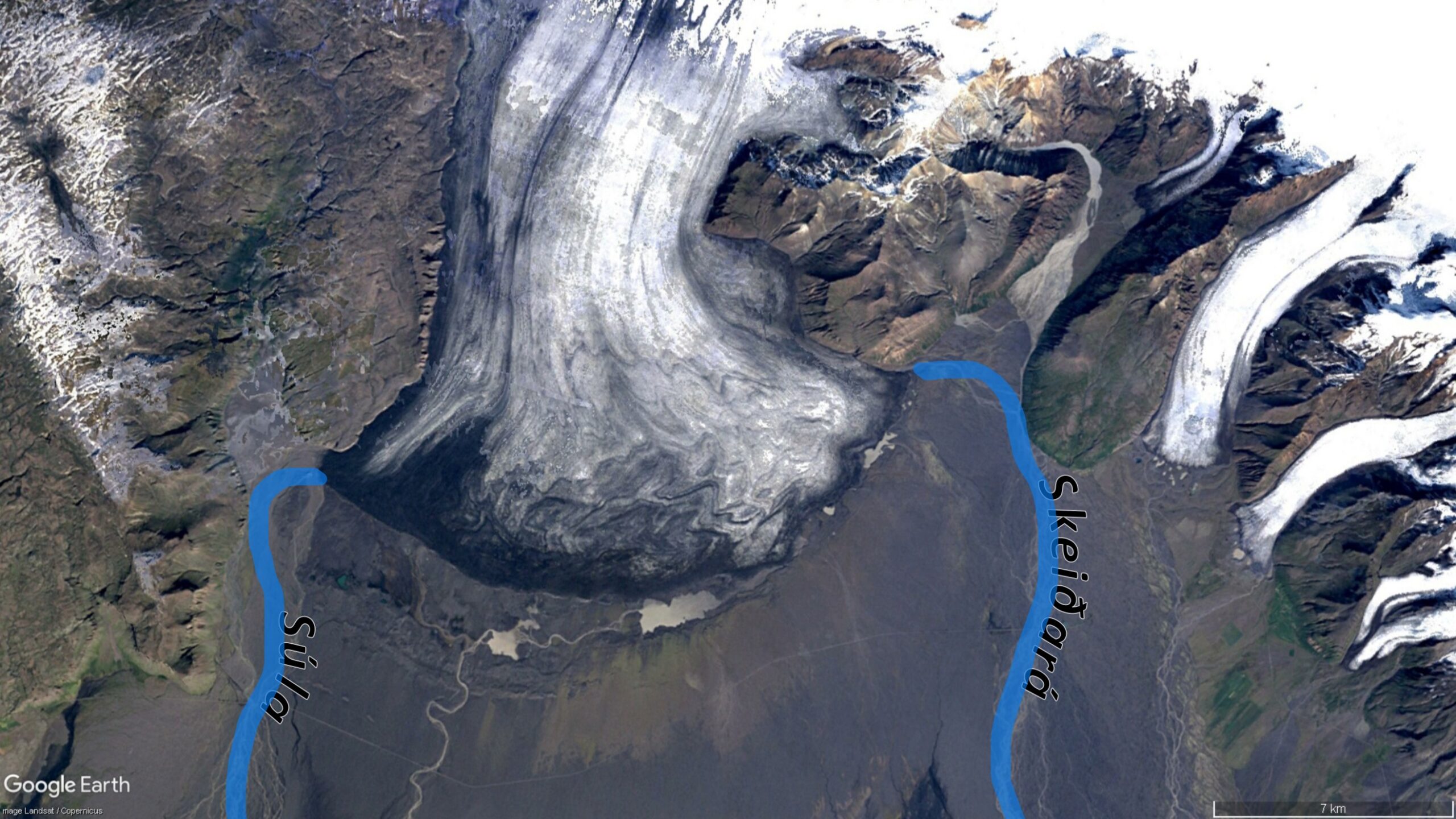

Where melt water emerges from underneath the Skeiðarárjökull, the landscape changes are no less impressive. This part of Skeiðarárjökull ‘always’ used to have its own meltwater river: Skeiðará river. Together with Súla (or Núpsvötn) river in the west they carried all of Skeiðarárjökull’s meltwater to the sea. It’s no coincidence both rivers emerge at the margins of the glacier, instead of in the middle. The fact that the glacier is just eight kilometers wide halfway but has an arch-shaped front of thirty kilometers wide makes the glacial flow to diverge and pushes the water to the sides.

Eastside of Skeiðarárjökull in 1974 (left) and 2023. Source 1974: Reykjavik Museum of Photography, photo INO 004 132 1-1.

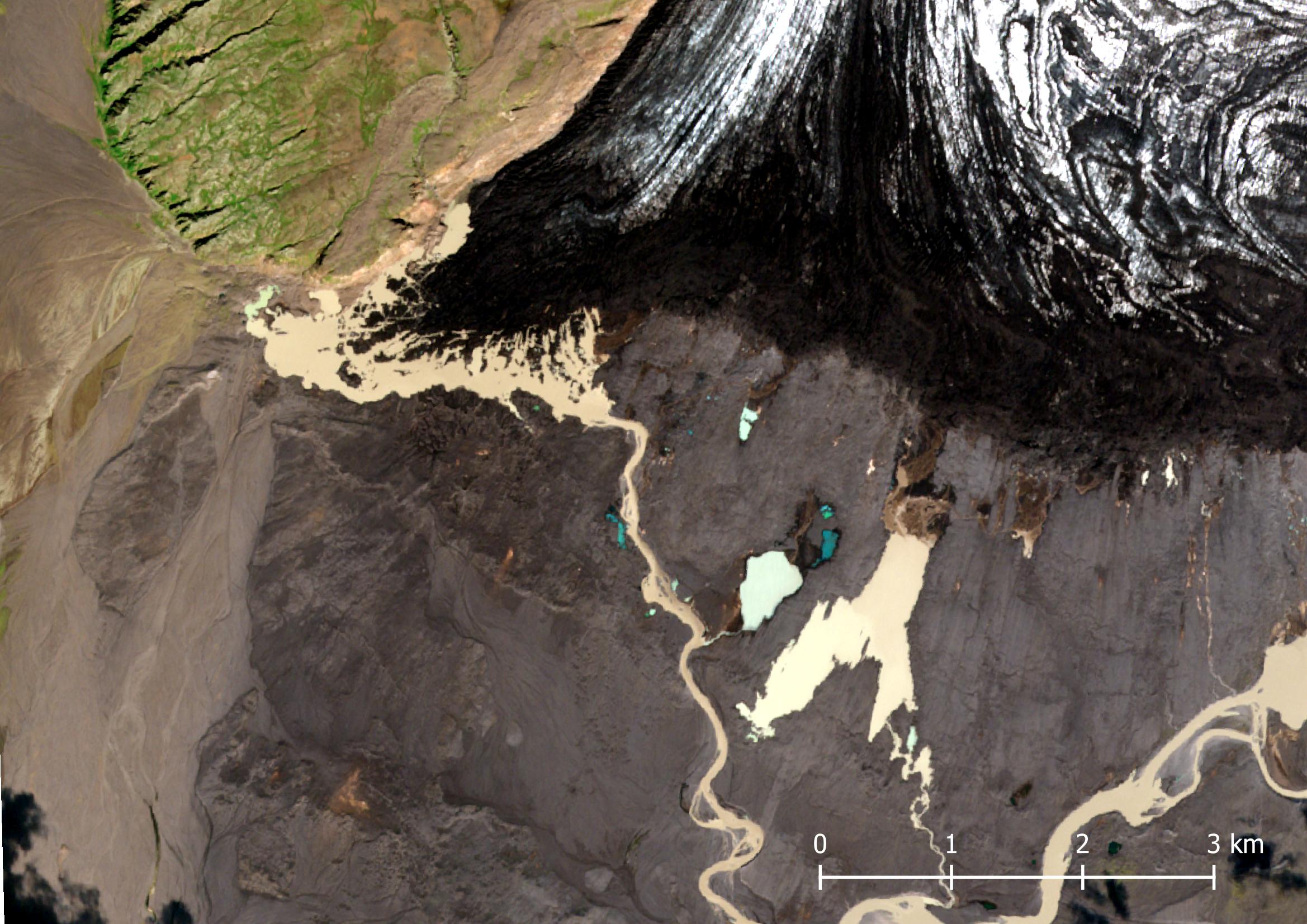

As Skeiðarárjökull changes, so do its rivers. The glacier has eroded a depression and has pushed up a wall of sediments around it, which is the outer moraine. Now the glacier recedes this depression is emerging, while at the same time jökulhlaups have raised the land beyond the moraine belt. This made it increasingly difficult for Skeiðará river to overcome the height difference. After all, a river doesn’t flow uphill. In 2004 this led to Skeiðará’s river bed to dry up. No longer does the river follows the course it has followed for many centuries. The nation’s newspaper headed: ‘’you can walk with dry feet in the river’’ (Morgunblaðið, 2004). Since then the river no longer flows directly to the sea, but first follows the glacier margin to merge with river Gígjukvísl, a relatively young river in the middle of the glacier snout. The same has happened with Súla river in the west. In total, Skeiðarárjökull has receded 2 (east) to 5 (west) km from its terminal moraine.

The (changing) course of Súla in 2015 (left) and 2023. Source: Sentinel-1 via Copernicus Browser.

Skeiðarárjökull and its rivers Skeiðará and Súla in 1985 (left) and 2020. Source: Google Earth.

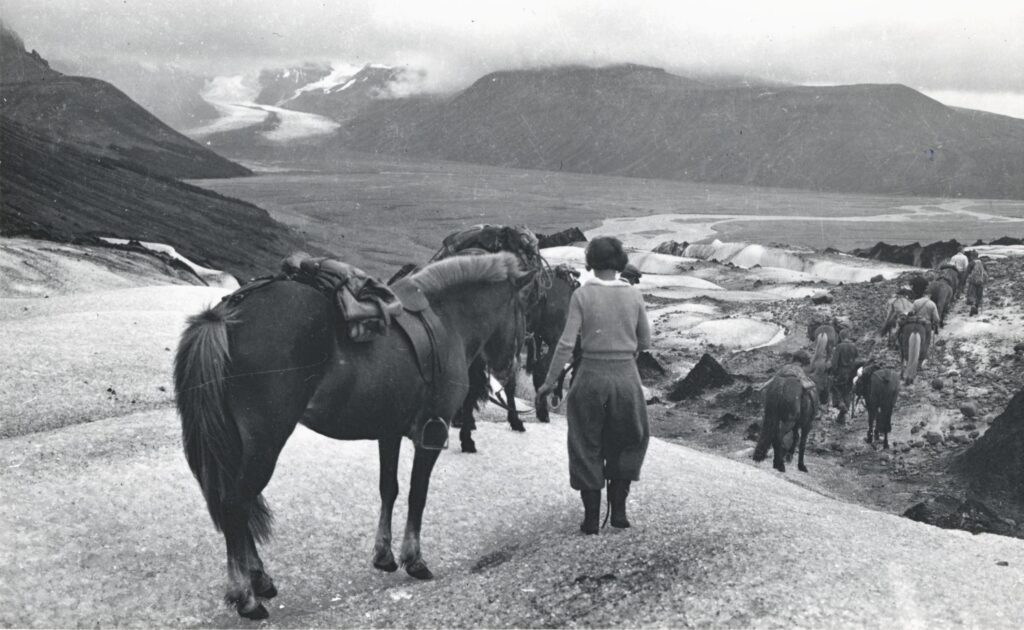

Not every dried up river makes headlines, but Skeiðará did thanks to its turbulent history. For centuries the river wreaked havoc upon local communities. From the middle of the sixteenth century Skeiðará began to break up agricultural land. After a jökulhlaup in 1861 the farmers were forced to move their farm up the slopes of Skaftafell (Björnsson, 2017: 393). The river was also a major obstacle for people traversing the Skeiðarársandur. Only with the help of the most experienced horses and guided by local people one could cross the strong and ever-changing river. An alternative was to get onto the glacier and pass the river that way, but this wasn’t without danger either.

It wasn’t until 1974 that Skeiðará river was bridged. Finally, traffic could drive all around the country. The bridge over Skeiðará spanned 964 m and was the longest bridge in the whole of Iceland. When it was built nobody had expected it to become useless within a few decades. But because of glacial retreat, people soon began to speculate about the river abandoning its course. Therefore, it was no longer a surprise when Skeiðará river indeed left its bed in 2004. The retreating Skeiðarárjökull made it possible for the water to flow along its margin to the middle of the glacier, joining Gígjkvísl. The long single lane bridge was replaced by a much shorter one in 2017. Núpsa river chose to merge with Gígjkvísl as well, in 2017. Since then all meltwater is carried to sea by this huge single river, making a jökulhlaup from Norðurdalur even harder to be noticed.

Search within glacierchange: