Directly south of the vast Vatnajökull ice cap, the glaciers of Öræfajökull tower high above the surrounding plains. The glaciated mountain catches the eye from afar and attracts a lot of clouds. Nowhere in Iceland it snows more than at the slopes of Öræfajökull.

Öræfajökull actually is a stratovolcano that erupted for the last time in 1362 and 1727. Those eruptions were so violently, that the area became uninhabited again and the name of the volcano was changed from Knappafellsjökull to Öræfajökull, which means wasteland glacier. Its 500 m deep and 3 km wide crater is now completely filled with ice (Magnússon et al., 2014). At the crater rim small mountains stick out of the ice. These are the highest peaks of Iceland, with Hvannadalshnjúkur on the northwestern rim being Iceland’s top summit at 2110 meters.

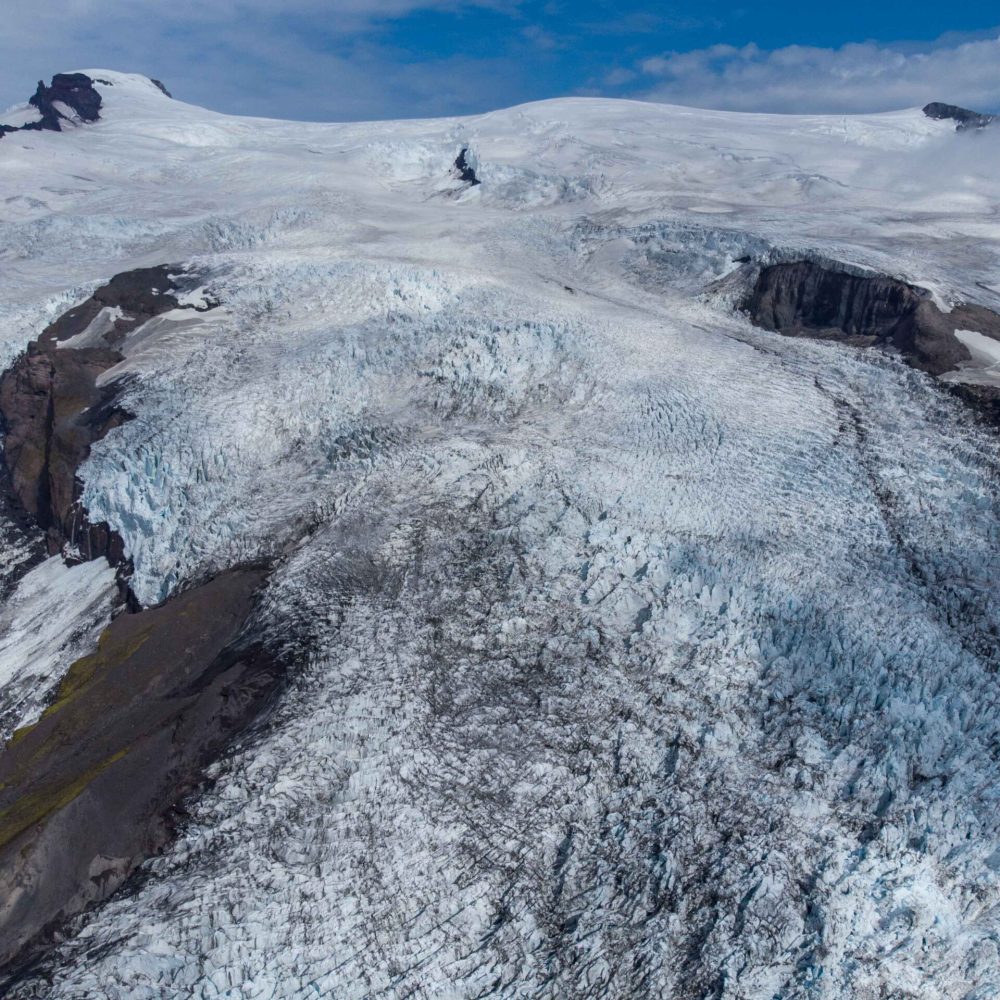

From the flat top of the Öræfajökull volcano, glaciers flow out in all directions. Nowhere in Iceland glaciers are as diverse as here: from steep icefalls, calving fronts and mazes of crevasses to flat valley glaciers. Some die halfway the slopes, others reach all the way to the plain. There they form Iceland’s highest moraines and beautiful glacial lakes. As the main road lies right next to most of these impressive glaciers, they are easy to visit.

With so many types of glaciers at close proximity to the main road, Öræfajökull is the perfect setting to learn about their past, present and future. In historical times most of the glaciers reached their maximum extent somewhere around 1850. All glaciers of Öræfajökull receded during most of the twentieth century and advanced slightly in the 1980’s thanks to increased snowfall. From the turn of the century melt increased, but remarkably some glaciers have advanced in recent years, again thanks to increased precipitation. In an ever warming climate this effect will be temporarily, though.

Search within glacierchange: