Silvrettagletscher (Silvretta Glacier) is a glacier on the border between Switzerland and Austria.

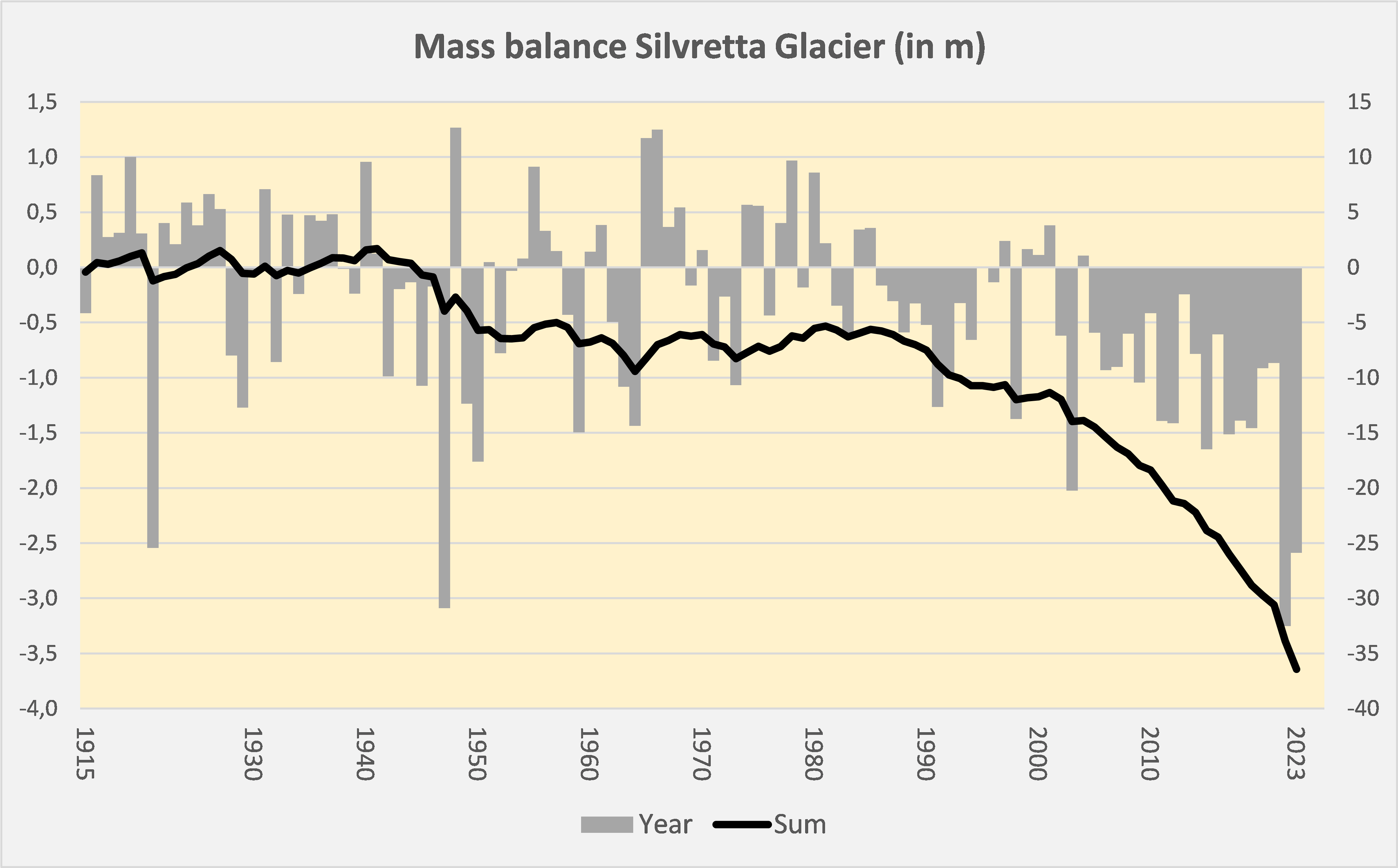

Silvretta Glacier is just over 2 km long and has an average thickness of 40-50 m. The glacier extends from 3100 m down to 2600 m, where its snout has a meltwater cave. Halfway the 19th century the snout reached further down, to 2100 m. To better understand its development, people started to measure snow thickness (in winter) and loss (in summer) already in 1915 on the glacier. Thanks to this very long measurement series, scientists now can look even further back in time.

30 km south from Silvretta Glacier lies God da Tamangur, Europe’s highest, purest, and most continuous forest of Pinus cembra (Swiss pine). Because the growth characteristics of this tree species are very sensitive to summer temperatures, they provide a unique opportunity to extends the glacier’s mass balance 200 years back in time. By analyzing its tree rings, past climate and therefore glacier development can be reconstructed.

For the analyses, scientists took samples of trees with an increment borer. They determined tree ring width, radial cell lumen diameter (size of cavities), cell wall thickness and stable oxygon isotope ratios. All these traits are influenced by climate conditions: some by summer temperatures, others by moisture and therefore snow thickness (Lopez-Saez et al., 2024).

The variation in pine tree traits compares very well to the mass balance record of Silvretta Glacier, like wider tree rings in years with a lot of melt (warm summers). Therefore, the trees can also tell us about the climate conditions before measurements began. They show that climate was most favorable for Silvretta Glacier in the period 1810-1820, possibly thanks to a number of volcanic eruptions and diminished solar activity. The tree rings further shows that the glacier started to downwaste in the 1860’s, which is sooner than temperature records suggest (Lopez-Saez et al., 2024).

Orthophotos of the snout of Silvretta Glacier in 1946, 1973, 1997 and 2022. Source: swisstopo.

During the 20th century mass loss dominated, only interrupted by short periods of slight mass gain. The last of such periods ended in the mid-1980’s and was followed by an important increase in summer melt, while the fraction of snow in the total precipitation lowered (Huss & Bauder, 2009). Just like all over the Alps, Silvretta Glacier lost unprecedented amounts of ice in 2022-2023.

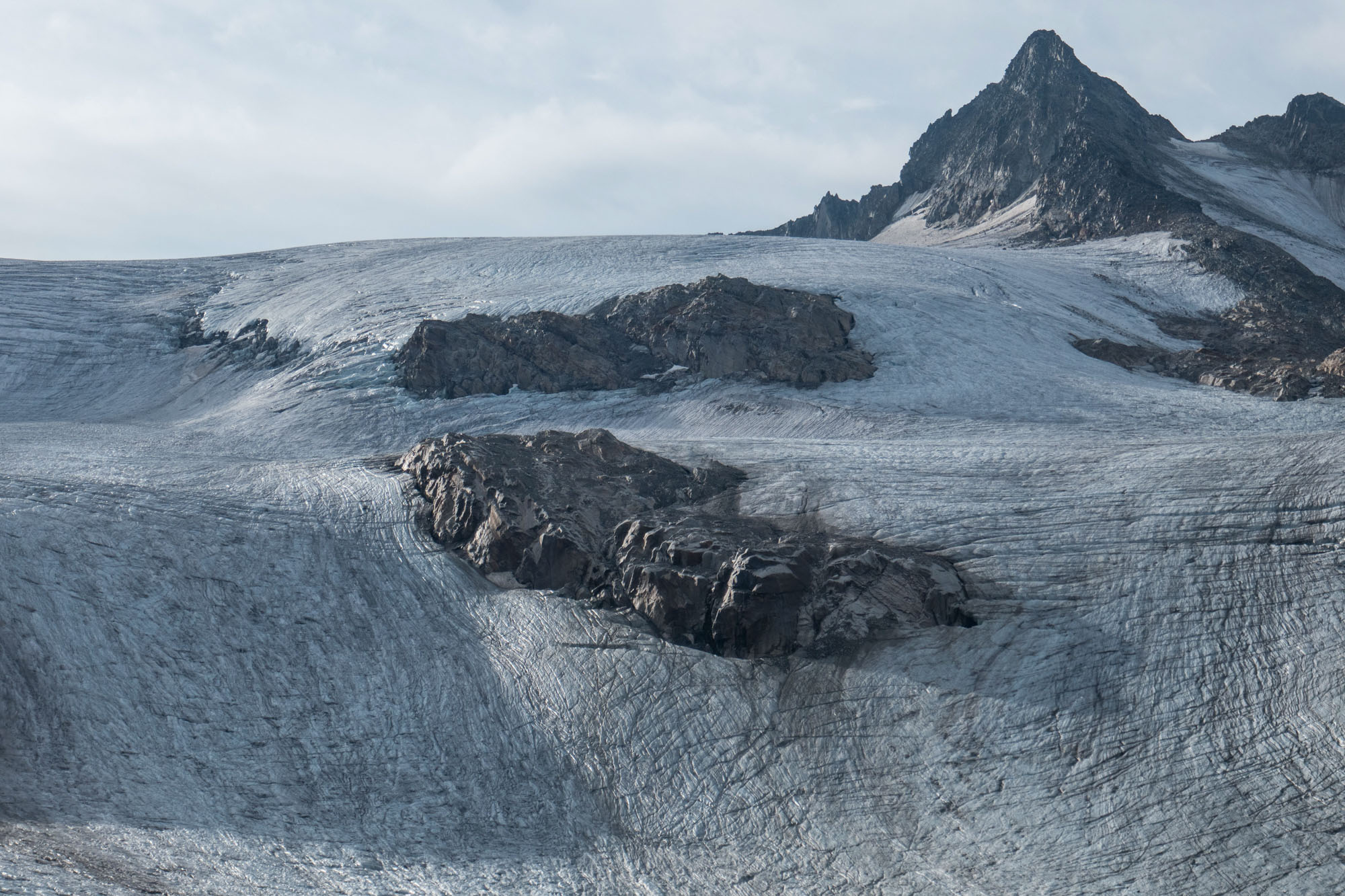

Due to the continued loss of ice, the glacier is shrinking and more and more rocks protrude the ice. With a mean ice thickness of 40-50 m and annual loss of 1.5 m, the glacier is gone within a few decades. And as the ice has entrained chemical pollutants for decades, its meltwater might harm people downstream (Miner et al., 2018).

It won’t be the first time that Silvretta Glacier becomes smaller than at present. That was also the case between 10.000 and 5000 years ago. Back then, trees were growing at higher altitudes in the Silvretta Massif and people could cross passes where ice had been before (Braumann et al., 2020). Only this time, it’s unfolding a lot faster.

Search within glacierchange: