Skaftafellsjökull must be the most famous glacier of Iceland. In front of the glacier is a large campsite and visitor center. Multiple glacier excursion companies have their lucrative base camp here. But you can’t book a tour on the Skaftafellsjökull itself, as it has receded too far.

Skaftafellsjökull is about 12 km long. It starts as two icefalls, each a kilometer wide and 400 m tall. One descends Vatnajökull, the other the Öræfajökull volcano. Where they merge lies a medial moraine. Its position indicates that the icefall from Vatnajökull transports two to three times more ice than the icefall from Öræfajökull. Ice thickness of the Skaftafellsjökull is 250 m on average.

To the west of Skaftafellsjökull is Skaftafellsheiði, a gently sloping hill covered in bushes, moorland and grasses. Partly because of this lush vegetation, the area was declared a National Park in 1967, the first in Iceland. The glacier itself formed most of the Park’s area, which was included in the much bigger Vatnajökull National Park in 2008.

Multiple studies independently concluded that Skaftafellsjökull reached its maximum extent in the years 1870-1880. They all based their claims on the basis of a technique called lichenometry, which involves measuring lichens and their growth rates. This way it can be determined when rocks were uncovered by the ice, as lichens can only start growing when they see daylight and their substrate (rocks) stop moving. One of the studies was conducted by M. Ómarsdóttir. She measured a staggering 2400 lichens, of which 300 on the outer moraine. Those 300 had an average size of 5 cm. Because growth rates were determined in other studies, Ómarsdóttir concluded that the outermost moraine must have been formed around 1870-1880 (Ómarsdóttir, 2007, Chenet et al., 2010).

Sixty years after Skaftafellsjökull reached its maximum extent, the Icelandic Meteorological Office started to measure the ice-front position of several glaciers, including Skaftafellsjökull. The beginning of systematic measurements coincided with the start of a relatively warm period in the 1930’s. From 1932 to 1967 the glacier retreated 1,3 kilometer, revealing streamlined moraines. These are broad arcuate ridges that predate the advance of the last centuries and potentially are over 2000 years old. Because the moraines were later overridden by the glacier, they have smooth surfaces with streamlined features such as flutings (Lee et al., 2018).

View towards the snout of Skaftafellsjökull in 1942 (Ingólfur Ísólfsson, Jöklarannsóknafélag Íslands) and 2023.

Although Skaftafellsjökull overall receded extensively in the 1930-1970 period, it occasionally experienced minor advances. During such events, rare hairpin-shaped moraines were formed. Hairpin moraines are a special kind of moraine with very long limbs and are produced by till squeezing into crevasses. This means the sediment underneath the glacier was soaked with water, making it susceptible to deformation. The till was then squeezed into the longitudinal crevasses of the glacier (Evans et al., 2017). When the glacier melts, the hairpin-moraines are left behind.

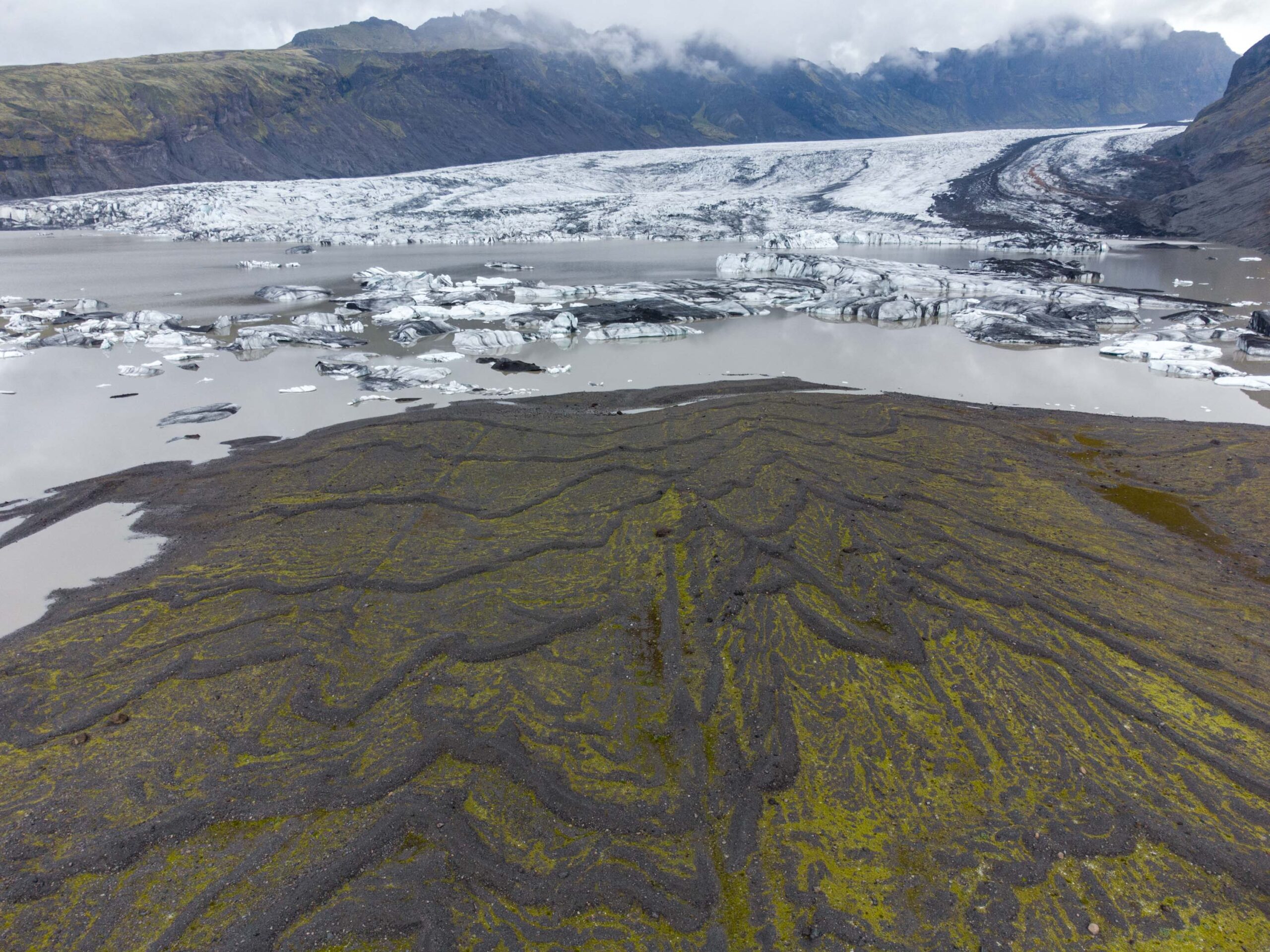

The period of strong recession ended in the 1960’s. In the following decades the front of Skaftafellsjökull was much more stable, culminating in a small readvance in the mid-1990’s. Because the front was more or less stationary for a long time, the glacier could construct a composite push moraine. This ridge is a prominent feature in the foreland of Skaftafellsjökull. Since then, the glacier receded more than a kilometer and now terminates in a proglacial lake. That’s why glacier excursions can no longer make use of Skaftafellsjökull and moved to nearby Fallsjökull.

In between the 1990’s-push moraine and the proglacial lake lies a series om small ridges, commonly no more than a meter high. These are recessional moraines, formed in winter when ablation (melt) is strongly reduced. As the glacier keeps moving forward, it actually advances slightly in winter and pushes up a new moraine. They are sawtooth in planform, because they reflect the morphology of the glacier snout. While those snouts are broadly arcuate in form, in detail they are full of radial crevasses or pecten (Evans et al., 2017). So when moving forward, a sawtooth ridge is formed. The following summer the Skaftafellsjökull recedes again, even further than the previous summer because the glacier is in overall recession. Next winter the glacier advances slightly, though not as far as the year before. Therefore the older recessional moraines are preserved and every year a ridge is added to this sequence. Nowhere is this process demonstrated better than in the foreland of Skaftafellsjökull, but the glacier stopped creating new ridges, as it terminates in a lake since 2010.

Skaftafellsjökull in 1976 (Hjálmar Bárðarson, Þjóðminjasafni Íslands) and 2023.

Skaftafellsjökull terminates in an overdeepened basin. This is a depression underneath the glacier snout. It was carved out during glacial advances in the last centuries. Sediments froze to the sole of the glacier and were transported to its margin, where meltwater carried the sediments away. Now that the glaciers are retreating, these overdeepenings become lakes. The overdeepening of Skaftafellsjökull stretches 6 km inland (with some parts being quite shallow), of which 5 are still occupied by the glacier (Hannesdóttir et al, 2015). Continued glacier retreat will thus reveal an ever-expanding lake. Thermal undercutting by lake water and calving can speed up the retreat of the margin (Lee et al., 2018).

Prior to 1935, the snouts of Skaftafellsjökull and Svínafellsjökull coalesced in front of mount Hafrafell. Local farmers used to graze their sheep on Hafrafell’s grassy slopes, but this mountain became less accessible as glaciers on either side of it advanced. Around 1700 the Svínafells- and Skaftafellsjökull merged, thus trapping Hafrafell in ice (Björnsson, 2017: 141). By 1935 the glaciers had receded to such an extent that Hafrafell was once again accessible.

Now that Hafrafell is no longer cut off, you can walk along the eastern shore of Skaftafell glacial lake and climb Hafrafell from there. A much harder climb to Hrútsfjallstindar (1854 m) also starts here. For the best views over Skaftafellsjökull you can walk up Kristínartindar (1126 m) at the other side of the glacier. A demanding yet rewarding walk, as you will encounter all special features of this prominent glacier.

Search within glacierchange: