Most outlet glaciers of Mýrdalsjökull are wide and long or narrow and short. Not Sólheimajökull: this southern outlet glacier is both long (12 km) and narrow (1 km). Its snout terminated at only hundred meters above sea level, making it the lowest descending outlet glacier of Mýrdalsjökull.

Sólheimajökull’s position close to sea level makes it a true tourist magnet. A paved road even winds its way from the main road to the parking lot (fee!) just one kilometer away from the glacier snout. Multiple companies have their base camp there for making glacier tours or kayak tours. In a single file people walk the seven hundred meters towards the viewpoint, from which it is another four hundred meters to the glacier. Increasing popularity of these climate sensitive places is associated with Last Chance Tourism: one in four people visiting Sólheimajökull is partly motivated by the idea that the glacier is disappearing (Hoogendoorn et al., 2021).

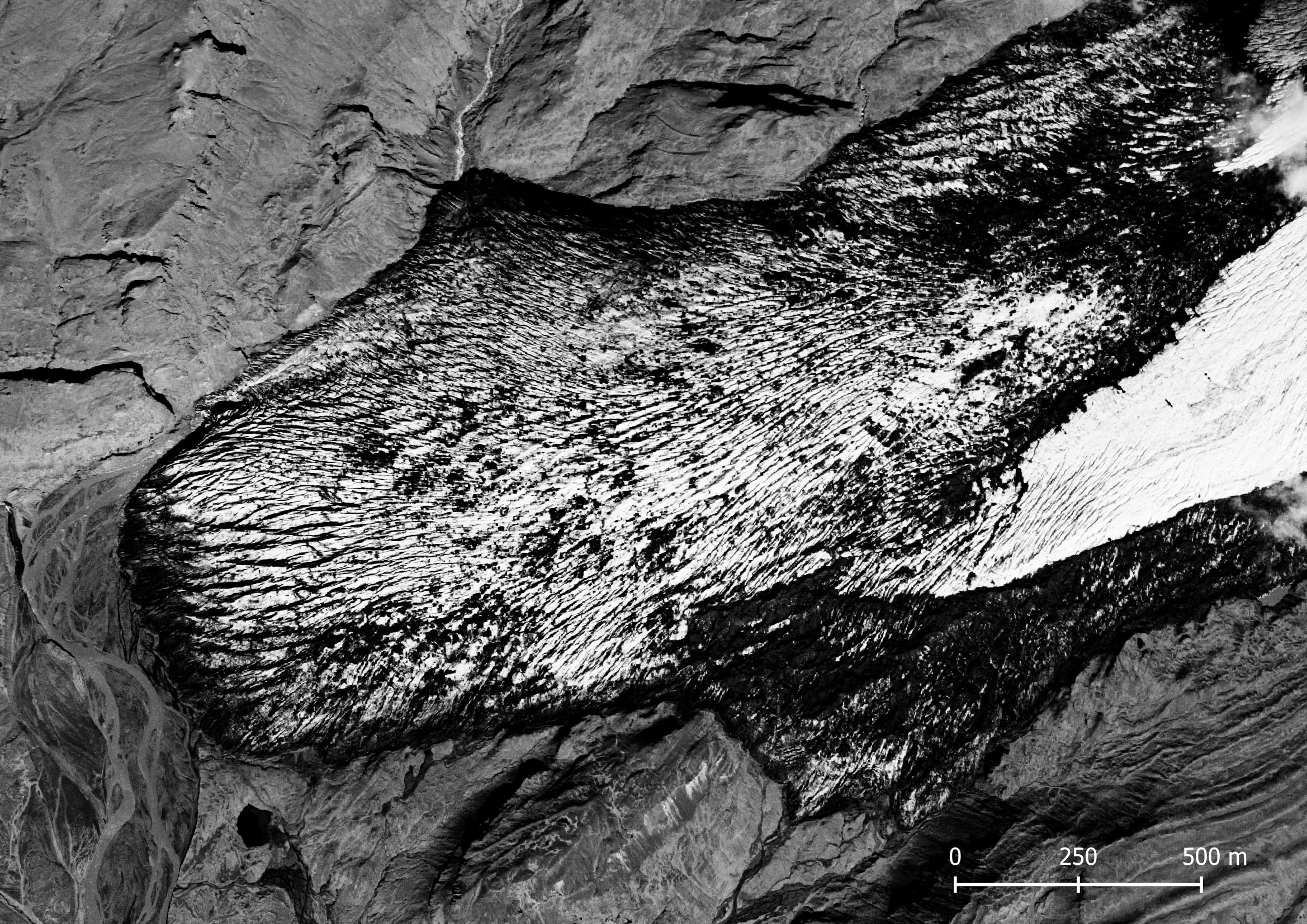

Sólheimajökull in 1990 (left) and 2021. Data: lmi.is/loftmyndasafn and Bing Aerial.

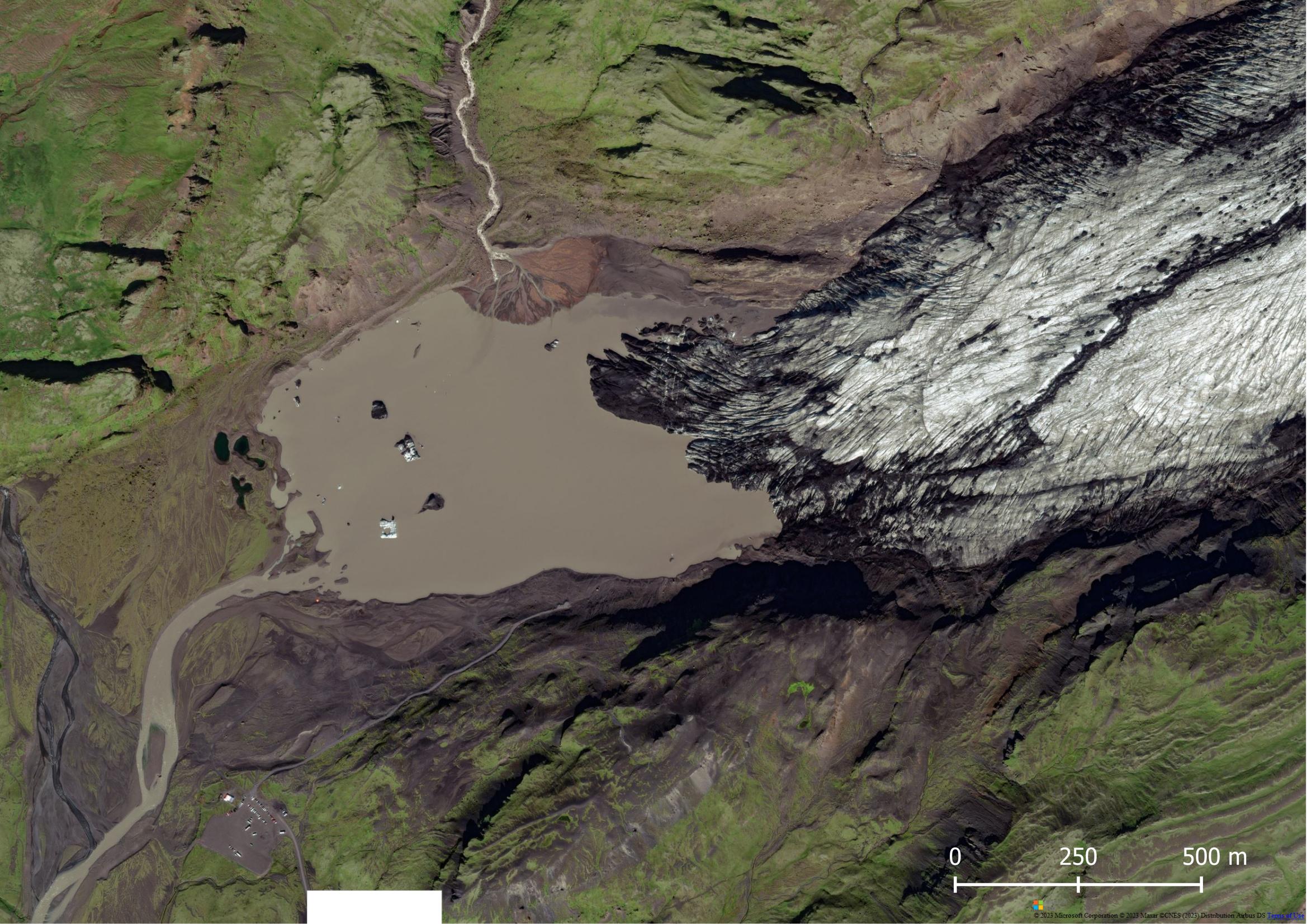

The footpath runs along a lake that was nonexistent before 2009. The depression was covered by ice for hundreds of years, gradually eroding this overdeepening. From the year 2000 onwards, the Sólheimajökull started to melt rapidly and ten years later the first parts of the lake were uncovered. Every year the lake has grown by about fifty meters, in expense of the glacier. This process was beautifully captured by one of the timelaps-cameras of Extreme Ice Survey, see https://vimeo.com/325061765. Sólheimajökull is currently the only outlet glacier of Mýrdalsjökull terminating in a lake.

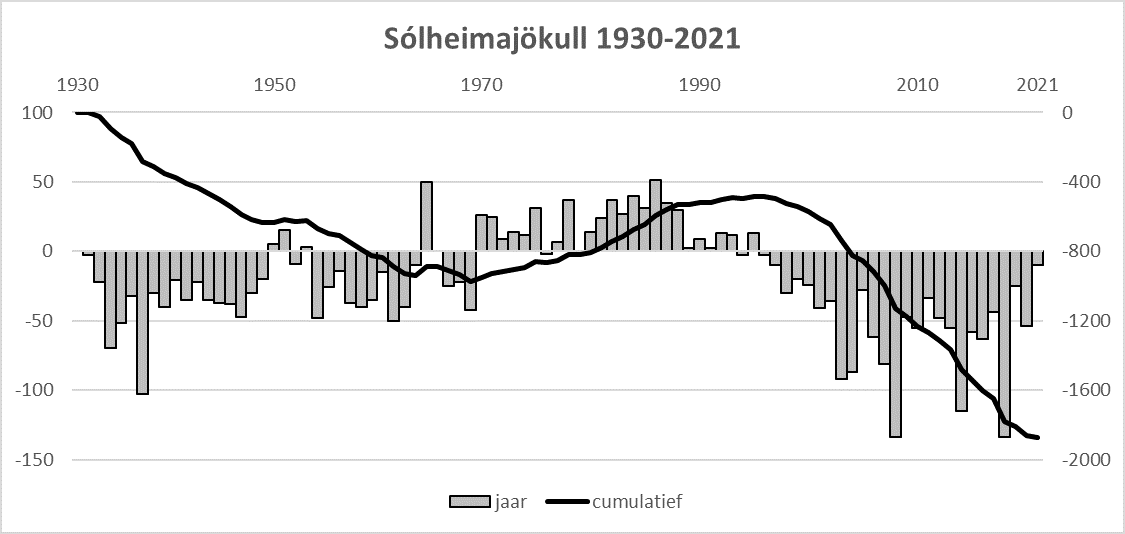

This is not the first time Sólheimajökull experiences shrinkage. When people began systematically measuring length changes in 1930, the glacier was also retreating. Between 1930 and 1970 it lost over a kilometer in length, followed by a period of advancement. The glacier regained half a kilometer, but lost 1,5 km in the last 25 years.

Sólheimajökull in 1930-1940 (left) and 2023. Photograher 1930: Jon Eythorsson, Jöklarannsóknafélag Íslands.

Length change data tells us in great detail how the Sólheimajökull behaved in the last century. To look further back in time, scientist have to turn to the surrounding landscape. High above the present-day glacier there is a series of moraines running parallel to each other on top op of the Hrossatungur. They were formed in times when the ice reached high enough to deposit debris there. By studying ash layers on top of the moraines, scientists were able to determine the minimal age of the moraines. This technique is called tephrochronology and showed that the outer moraine is between 4500 and 7000 years old, the innermost one must have been formed about 1200 years ago (Dugmore, 1989).

It is exceptional that Sólheimajökull’s outermost moraines are this old. While neighboring glaciers reached their maximum Holocene extent no longer than one or two centuries ago, Sólheimajökull was at its biggest thousands of years earlier (Casely and Dugmore, 2008). This Sólheimajökull-anomaly is probably due to shifting ice divides. Long ago a much bigger part of Mýrdalsjökull drained towards Sólheimajökull. Only when the ice cap grew bigger over millennia, more ice flowed to other sides. Paradoxically, Sólheimajökull received more ice when the ice cap was smaller (Dugmore and Sugden, 1991).

Does this paradox bring hope for the future? No. Mýrdalsjökull is disappearing too fast to be hoping for any positive outcome for Sólheimajökull. Climate change causes more ice and snow to melt. Although snowfall also increased between September and may (Gómez et al., 2020), it does not sufficiently counterbalance the prolonged and intensified period of summer melt. Some steeper outlet glaciers did indeed stabilize thanks to an increase in precipitation, but the response time of Sólheimajökull is much slower than those short and steep glaciers.

Sólheimajökull responds much slower to changes in temperature and precipitation because of its length. With an average velocity of hundred meters a year it takes decades for an increase of snow at the accumulation zone to translate into more ice influx at its snout. Besides, the glacier is not at all in balance with the current climate. So even if climate change would stop right now, the glacier would still recede by thousands of meters before reaching an equilibrium. It may look like the recession slowed down in recent years, but that’s only because of glacier bed topography: over the period 2009-2019 the snout disintegrated extra rapidly in the expanding lake. By now, the glacier has reached more shallow waters at the other end of the lake.

Let’s hope for the Last Chance-kayakers that Sólheimajökull will keep producing icebergs for a few more years.

Search within glacierchange: