In the middle of Switzerland lies Steingletscher, also known as Steigletscher. This 3 km long glacier has receded quickly over the last decades, which has offered new research opportunities.

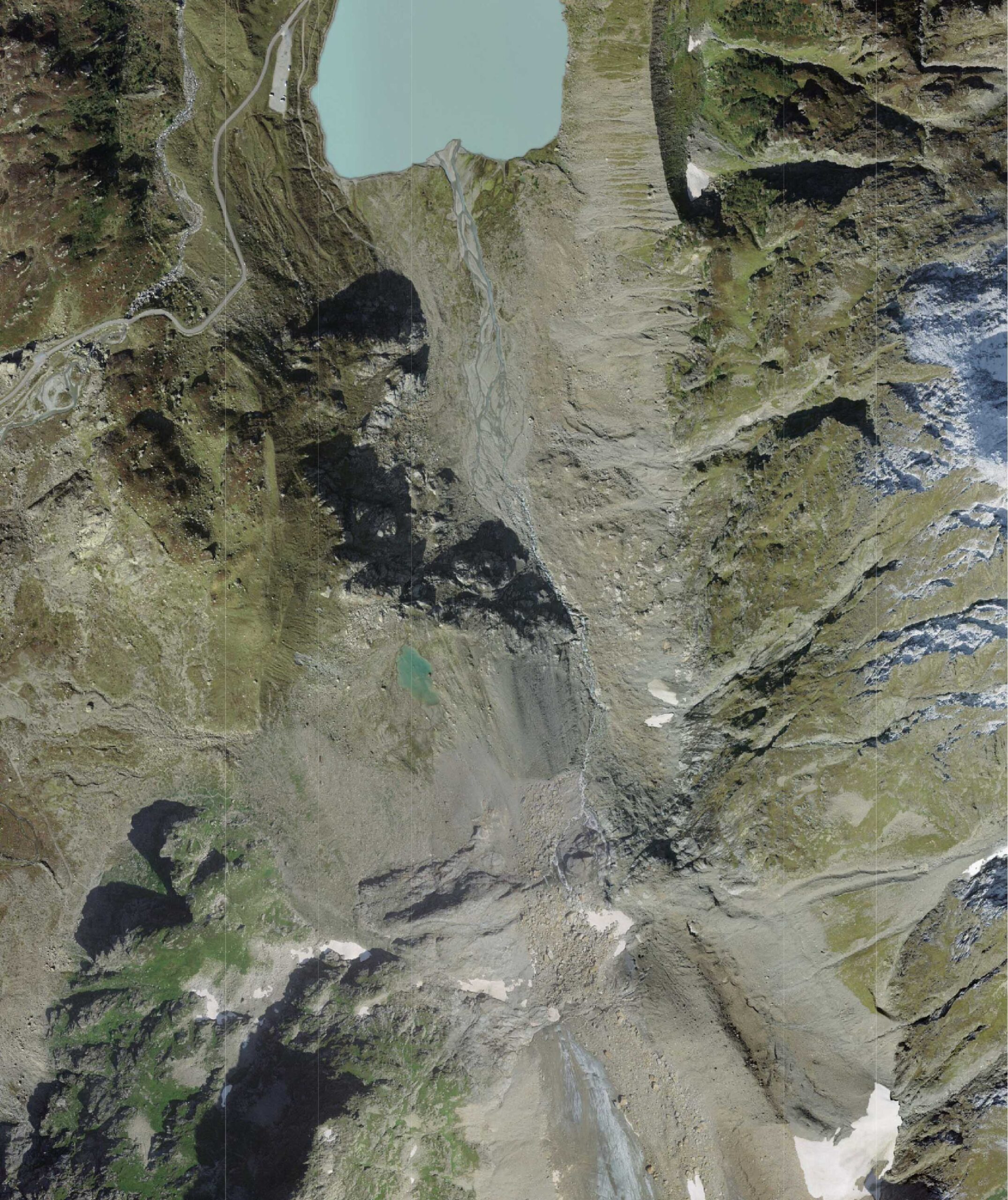

Steingletscher in 1986 (left) and 2021. Source: swisstopo zeireise.

Steingletscher descends from mountains like Sustenhorn (3502 m) and Gwächtenhorn (3404 m) three km down in a northerly direction. At the beginning of the 21th century, the snout of Steingletscher was still very close to the main road (Sustenpass) and was therefore very easy to visit, especially in the 1970’s and 1980’s when the glacier advanced. In those days, most glaciers in this part of the Alps were growing, though not nearly reaching their 1850 maximum extents.

In the nineteenth century, Steingletscher reached all the way to where Hotel-Restaurant Steingletscher is now, at the Sustenpass. Afterwards, the glacier receded and eventually a lake (Steisee) was revealed. After receding a kilometer, the glacier advanced again by 250 m between 1970 and 1990. In this period the snout looked very different, as growing glaciers have a steeper front. Eventually, the Steingletscher reached into the lake again for a few years.

The period of advancement was followed by strong retreat, especially from 2000 onwards. Due to a collapsing rock face in 2020, the glacier’s snout is largely covered by rocks. Now the snout is hardly recognizable as such, one has to hike to the Tierberglihütte (2750) in order to see a decent piece of glacier. The mountain where the hut sits upon used to be enclosed by ice. But the glacier (Steilimigletscher) that occupied the landscape to the east has disappeared completely.

Now the ice is disappearing, new research opportunities emerge. When rocks of Chuebergli (Chööbargli) were freed from the ice around the year 2000, scientists were eager to take samples of them. They tested the rocks for beryllium, because the concentration of the radioactive isotope Be-10 indicates the number of years that the rocks have been exposed to sunlight. The rocks must have been deprived of it at the end of the last ice age (11.700 years ago), as glaciers had eroded all surfaces influenced by the sun.

Thanks to previous research, it was already known that the lower part of Steingletscher disappeared around 10.000 years ago. From the beryllium tests is was shown that the rocks of Chuebergli were exposed to sunlight for 7000 years since then. Only 3000 years ago Steingletscher grew big enough to cover these rocks by ice again. Since then, only short-lived periods of limited glacier extent occurred, but these were exceptions in a generally glaciated valley, at least at the specific spot where the samples were taken from (Schimmelpfennig et al., 2022).

![Steinlimmigletscher [Steinlimigletscher] Walking on Steingletscher with Steilimigletscher in the back, 1904. Photographer: Leo Wehri, Library ETH Zürich Dia_247-00584.](https://glacierchange.com/wp-content/uploads/elementor/thumbs/Dia_247-00584-scaled-qpvw37j0d3q6oec2shfz6or3p8k8abygc1f8sywoe2.jpg)

Does this mean Steingletscher was bigger in 2000 than it had been during the period 10.000-3000 before present? Not necessarily. When the rocks were exposed in ca. 2000 the glacier should have been much smaller already, based on temperature data. But melt rates can’t keep up with the warming climate, just like the glaciers in the Alps would still disappear even if global warming stops right now. It takes some 50 years for the glaciers to adjust to a new climate, meaning that Steingletscher has in fact been smaller for 7000 years than it was in 1950 (Schimmelpfennig et al., 2022).

The findings at Steingletscher are comparable to previous results and help to reconstruct glacier behavior during the Holocene (that’s how the geological era is called that succeeded the last ice age). But it’s still difficult to determine what the climate in the Alps exactly was like. The beryllium test, for example, doesn’t tell us anything about the minimal extent of Steingletscher. Was it completely gone for thousands of years, or just a little smaller than in 1950? As more and more rocks get uncovered at higher altitudes, new tests will reveal how long they have been ice-free. This helps to put our future in a geological perspective.

Search within glacierchange: