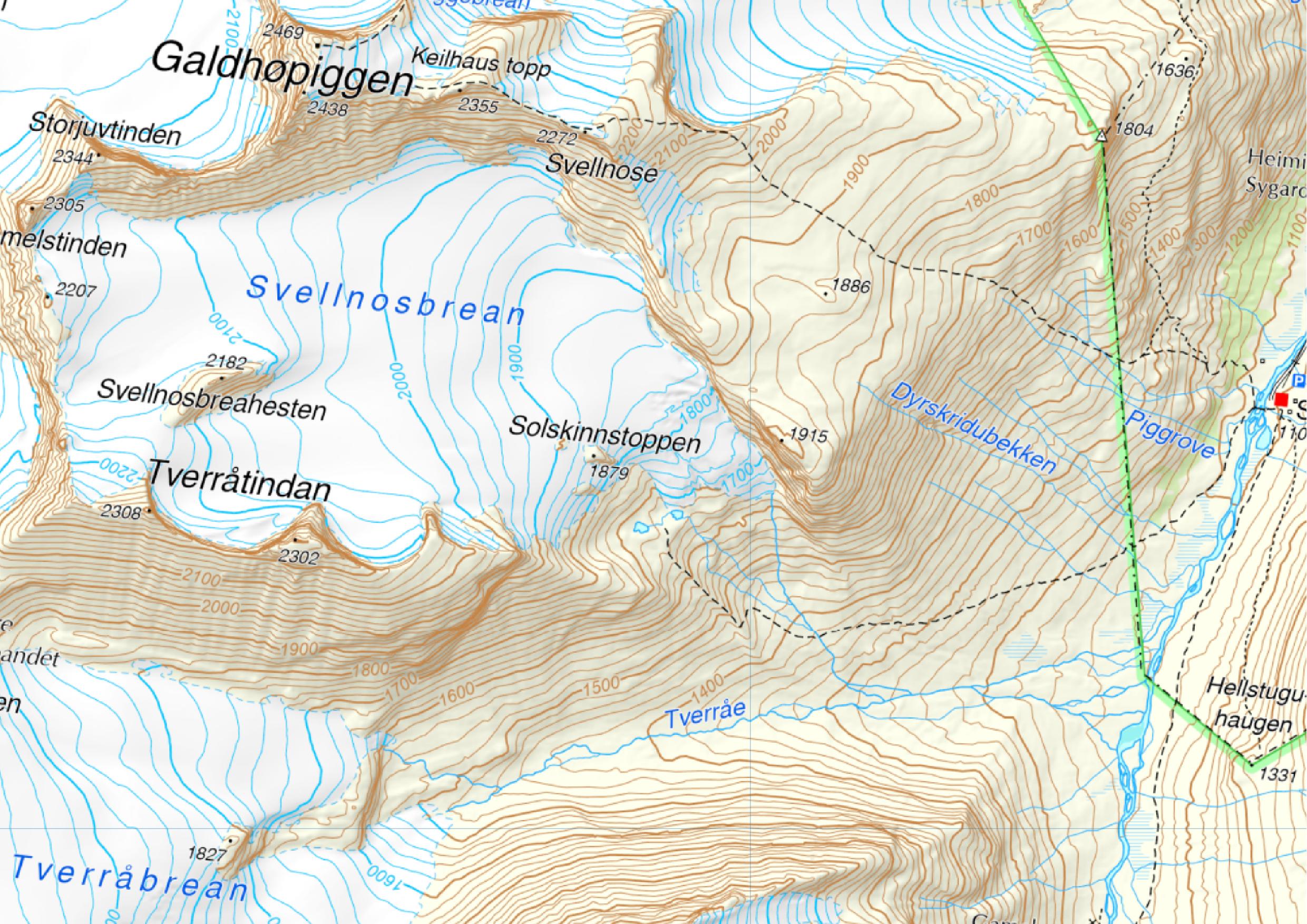

Svellnosbrean is a glacier in Jotunheimen, an mountainous region in central South-Norway. The glacier is four kilometer long and starts directly below Galdhøpiggen, Norway’s highest mountain. From the nearby mountain hut Spiterstulen, glacier tours to Svellnosbrean are organized.

Like most glaciers in Jotunheimen, Svellnosbrean is a cirque-glacier. This means it forms in a bowl-shaped depression surrounded by steep mountain slopes. But Svellnosbrean is not restricted to the cirque: the bowl accumulates sufficient amounts of snow for the glacier to flow further downstream.

Nowadays the glacier terminates just abov a steep cliff. It can’t form any moraines there, because debris falls down immediately. How different from a century ago, when the glacier ended four hundred meters lower. It formed eleven moraines in the valley: small ridges of shoveled stones, a few meters high. Some are preserved very well and span the entire width of the valley, others are eroded and are a few dozens of meters long at best.

Researchers have tried to date the moraines. That’s an easy thing to do for the youngest one, because pictures were taken around the time it was formed (1930). And the oldest one must have been formed in the period when all glaciers in Jotunheimen reached their maximum extent, around 1750. To date the nine intermediate moraines, two techniques were used. First, Ffoulkes and Harrison took a rebound hammer or Schmidt hammer to test the strength of rocks, which indicates the exposure ages of moraines (Ffoulkes en Harrison, 2014). The second technique that was used at Svellnosbrean is called lichenometry, by which lichens are measured to determine the number of years a rock appeared from underneath the glacier.

Both techniques are far from ideal, the Schmidt hammer even less than lichenometry. The results from these methods therefore differ and both have their errors. The fourth youngest moraine, for example, was formed in 1854 according to the Scmidt hammer technique, while it was created in 1886 based on lichenometry. Therefore, scientist always try to use multiple techniques on a wide range of locations before making statements about regional glacier behavior. Following this procedure, four clear periods of glacier advance in Jotunheimen emerge: 1740, 1850, 1890 and 1930 (Matthews, 2005).

Most hikers who visit Svellnosbrean are not too interested in old moraines. Instead, they come here to see the special blue colours in the glacier for themselves. To do so, they start in groups at Spiterstulen. The walk takes 2,5 hours and gets a little bit longer every year, as the glacier recedes. The steepest part of the hike follows the top ridge of Svellnosbrean’s old lateral moraine, a very high one for Norwegian standards.

For those wanting to see Svellnosbrean from above, Galdhøpiggen is an excellent viewpoint. From the top of Norway’s highest mountain you can see virtually all of Jotunheimen. Down below, Svellnosbrean often lacks a cover of fresh snow. As temperatures rise, less and less snow survives the summer to become new ice. And existing ice keeps melting, so the glacier is shrinking fast. In the end, there won’t be a glacier to guide people to anymore.

Search within glacierchange: