Vesljuvbreen (aka Juvbreen) is a small glacier in Jotunheimen, supporting Norway’s highest ski center. It used to confluence with Kjelbreen (sometimes referred to as Vesle-Juvbreen or Kjelen).

Vesljuvbreen descends from the plateau of Galdhøe at 2200 m to Juvvatnet, Norway’s highest lake at 1840 m. All in all, the glacier is just over 1 km long and no more than 500 m wide. Even though the glacier is small, it’s well known thanks to the ski area on its surface. This Galdhøpiggen Summer Ski Centre is Norway’s highest ski centre.

The summer ski centre provides professional skiers and other fanatics the opportunity to practice their beloved sport year round. But the ski centre is feeling climate change as well. In 2006, after dozens of years in operation from May til October, the centre had to close in summer for the first time in its history. The reason: a lack of snow.

In 2006 the lack of snow at Vesljuvbreen made the headlines (nrk.no). But what was remarkable in 2006, had become the new standard in 2015. That year, the fact that the ski area could stay open throughout the summer was newsworthy, instead of its closure (nrk.no). Now, snow is stored under white canvases to open as soon as possible in autumn, when the first fresh snow arrives.

A lack of snow doesn’t only impact skiing conditions, it also harms Vesljuvbreen. When the glacier isn’t covered by snow, the ice starts melting. In 2018-2019 it had thinned and receded by so much, that the ski lift had to be moved: the expanding Juvvatnet was getting dangerously close to the lift.

Vesljuvbreen and Kjelbreen (in the far right) in 1890 and 2024. Photographer 1890: Knud Knudsen, University of Bergen Library photo ubb-kk-2127-1500.

For a long time Vesljuvbreen was connected to Kjelbreen, a small cirque glacier beneath a 300 m high headwall. Together they terminated in lake Juvvatnet. As the glaciers are located along the easiest route to the top of Galdhøpiggen (Norway’s highest), both glaciers were ‘in the picture’ early on. They show a broad calving front. Vesljuvbreen has completely retreated from the lake, Kjelbreen is about to disappear into it.

Old photos show how the glaciers have developed over the last 150 years, but their history goes back much further. To investigate this, divers took a sediment core from the lake floor. The lake sediment characteristics (density, minerals and magnetic susceptibility) reflect the glacier activity. An advancing glacier has more erosive power than a retreating one, for example.

The sediment core of only 54 cm long spans 4000 years of sedimentation. It shows that glacier activity increased from about 2000 years ago, remained high over the last thousand years and peaked some 250 years ago (Nesje et al., 2012). That matches well with the timing of the Little Ice Age (LIA), when glaciers in south Norway were most extensive.

![Vesljuvbrean Rephoto II 1900-1970 (small) Nasjonalbiblioteket URN_NBN_no-nb_digifoto_AE2000143787_0135_F_01 Vesljuvbreen and Kjelbreen in ca. 1940. Source: National Library of Norway, 'Postkort fra Jotunheimen [bilde 135]'.](https://glacierchange.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Vesljuvbrean-Rephoto-II-1900-1970-small-Nasjonalbiblioteket-URN_NBN_no-nb_digifoto_AE2000143787_0135_F_01.jpg)

Vesljuvbreen and Kjelbreen in ca. 1930-1940 and 2024. Source 1940: National Library of Norway, ‘Postkort fra Jotunheimen [bilde 135]’.

Somewhere in the period 1950-1970 Vesljuvbreen and Kjelbreen got separated. Since then Kjelbreen kept on calving in Juvvatnet. A path leads to the glacier. It crosses two ice-cored moraine ridges via steps constructed by Nepalese people. The ridges were formed a few hundred years ago, when the glacier was at its LIA maximum (Matthews, Winkler & Wilson, 2014).

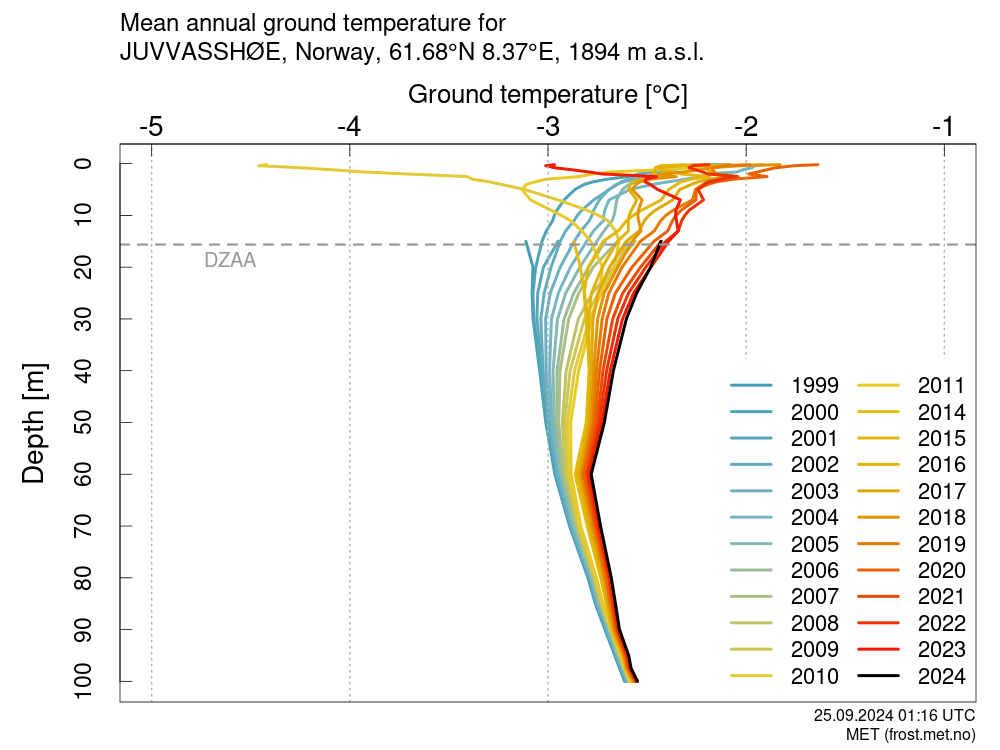

Melt isn’t limited to glaciers and snow. At this high altitude in an arctic climate, the ground is also frozen. These year-round frozen soils are called permafrost. At Juvvasshøe, only one km from the glacier, there is a borehole station to monitor permafrost conditions. Temperature is being measured up to 100 m deep, but the permafrost may stretch as far down as 300 m!

In summer, the upper 2.5 m of the soil thaws. This is called the active layer. Because of climate change the active layer reaches deeper and deeper. Though the rest of the soil stays frozen, it’s warming as well. Even 100 m beneath the surface temperatures are very slowly rising. So even those who bury their head in the sand can’t escape from global warming…

Search within glacierchange: